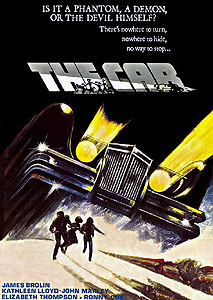

The Car/Deathmobile (1977) ***

The Car/Deathmobile (1977) ***

I had never thought of Orca and The Car as a mutually resonant pair of movies; they were merely the two films that my girlfriend and I were in the mood to watch one night not long ago. It turned out to be an immensely resonant pairing, however— so much so that I wouldn’t hesitate to use it again if I ever found myself being asked to program a double feature somewhere. This is because each film represents, in its own way, an extreme mutation of the Jaws phenomenon, with results not merely opposite to each other, but also opposite to what one would naturally expect in each case. Orca was more a cash-in than a direct rip-off, for beyond revolving around the rampage of a homicidal marine predator, it owed little to Jaws in terms of plot or characterization. In much the same way as with The Omen’s derivation from The Exorcist, the inspiration was primarily commercial; Orca would most likely never have existed without the mammoth success of Jaws, but the two pictures don’t much resemble each other in detail. At the very least, you certainly can’t accuse Orca of slavishly copying Jaws on the tonal front, because no other animal-attack movie I’ve seen ever asked the audience to side against the humans. A killer whale, meanwhile, is a fairly credible thing to press into service as a movie monster. Although there are no documented cases of humans ever being attacked by a wild killer whale, captive orcas have on occasion proven themselves extremely dangerous to their keepers. That combination of independent-mindedness and plausibility usually describes the correct approach to coattail-riding, and were it not for the involvement of Dino De Laurentiis as producer, all the signs would point toward Orca being a creditable enough take on its formula. By contrast, The Car, as unlikely as this may sound, is among the purest rip-offs that Jaws ever had, right up there with Grizzly. It takes the story of Jaws, plot point for plot point almost, and transposes it from the mid-Atlantic coast to a small New Mexico desert town, replacing the killer shark with— are you ready for this?— a hotrod Lincoln built and operated by Satan! Surely there’s no possible way this isn’t the stupidest big-studio monster movie of the whole 1970’s, right? And yet those completely reasonable expectations would lead you to get it exactly backwards. Orca is the justly infamous imbecile anti-classic, while The Car is a much better film than it has any business being.

Much as Jaws began with a young couple slipping away from a beach party to go swimming by themselves, The Car kicks off with Suzie Pullbrook (Melody Thomas, from Piranha and The Fury) and her boyfriend, Pete Keil (Bob Woodlock), biking down one of the two state highways that pass through whatever little hamlet they call home on the way to an overnight campout in the desert. This works out about as well for them as the midnight skinny-dip did for the kids on Amity Island. As the campers approach the bridge passing high over the river that makes this part of the countryside minimally habitable, they are come up on from behind by a freakishly customized luxury coupe (my best guess is that it started life as an early-70’s Lincoln Mk III, but customizer George Barris did a masterful job of rendering it almost unrecognizable), and run off the road. Suzie’s battered body lands in a gorge beside the highway, visible to passing traffic, but Pete goes straight into the river. It’ll be hours before an old man hooks his corpse while fishing.

Shortly thereafter, the same vehicle flattens Johnny Norris (John Rubinstein, of Something Evil and The Boys from Brazil) as he hitchhikes his way eastward toward home from California. I do mean flatten, too— the mutant Lincoln runs over the unfortunate lad no fewer than four times before its unseen driver is satisfied! There’s a witness to this second attack, though, for Norris was killed right outside the home of demolitionist, wife-beater, and all-around bastard Amos Clements (R.G. Armstrong, from The Legend of Hillbilly John and The Pack). Amos, to his rare credit, finds a moment to call the police in between slaps to Bertha’s face (Bertha is played by Doris Dowling), and soon he’s trying to explain what he saw to Everett the Thomas County sheriff (John Marley, of The Dead Are Alive and Deathdream) and senior patrolman Wade Parent (James Brolin, from Westworld and Capricorn One). Amos’s testimony is somewhat unhelpful. The Clements house fronts onto an unpaved road, and it hasn’t rained in ages. Consequently, Amos could see only well enough to form a vague impression of dark paint, two doors, and a lowered roofline through the clouds of dust kicked up by the car’s wheels. He also doesn’t recall seeing a license plate.

It doesn’t take Everett or his men long to figure out that Johnny Norris and the teenaged campers were killed by the same person. The sheriff has Donna the dispatcher (Geraldine Keams) send word to the cops in neighboring Dagler County that a psycho gearhead is on the loose, and gives orders to put a prowl car on station to watch each of the four routes out of town, plus another to monitor the on-ramp to the interstate just to be sure. Then he turns his attention back to a recurring project of his, trying to persuade Bertha Clements (whose facial bruises were far too obvious to be missed that morning) to press charges against her husband. That’s a personal matter for Everett as well as a professional one, because Bertha was his high school sweetheart, and he still cares deeply for her some 45 years later. It’s a lost cause, though, and Everett is so shaken up by the time he’s forced to admit that there’s nothing he can do but release Amos and send the Clementses on their way that he heads across the street to the bar for a whiskey or two after his shift at the station is over. He never gets that much-needed drink. The Murdermobile has been parked down the block for who knows how long, and it smashes the sheriff as he mounts the curb in front of the bar— swerving round Amos Clements (who was also on his way to the pub) as it does so.

Thus it is that Amos finds himself being questioned about a hit-and-run homicide for the second time in 24 hours. There was another witness, too, an old Navajo lady (Margaret Willey), but she doesn’t speak a word of English. Luckily, Wade (now stepping up as acting sheriff) has two bilingual Navajos on his staff in Donna and a patrolman called Chas (Henry O’Brien). The only bit of information the woman has that they couldn’t have learned from Clements is so strange, though, that neither interpreter believes it, and Wade doesn’t hear about it until later, when the rapidly escalating weirdness reaches the point where nothing seems too crazy to be considered. She says there was nobody driving the car.

Be that as it may, Everett’s death puts the whole force on what amounts to a war footing. Manning at the roadblocks is doubled wherever Wade can spare the personnel for it, and he starts thinking about how to limit the killer’s supply of available targets. With the latter in mind, he orders his regular partner, Luke (Ronny Cox, from Deliverance and The Beast Within), to call the school, and to ask Miss McDonald the principal (Kate Murtagh, of Switchblade Sisters and The Night Strangler) to cancel the afternoon’s parade rehearsal. Again there is a personal dimension to this course of action, for Wade’s daugthers (Kim Richards, of Escape to Witch Mountain and Assault on Precinct 13, and Kyle Richards, from Eaten Alive and The Watcher in the Woods) are marching in said parade, and its organizers are a pair of young art and music teachers named Lauren (Kathleen Lloyd, from Sorority Kill and It Lives Again) and Margie (Elizabeth Thompson, later of The Crow and The Rejuvenator), who are dating Wade and Luke respectively. Alas, Luke is a recovering alcoholic, and the stress of the past 30 hours or so has knocked him right off the wagon. Luke gets drunk as soon as the rest of the cops take their positions, leaving him effectively alone in the station, and Miss McDonald never gets Wade’s message about the parade.

The parade rehearsal, as you’ve probably guessed, is The Car’s answer to the Fourth of July. The Murdermobile bypasses the roads (and Wade’s checkpoints along with them) by driving straight across the desert flats, catching Miss McDonald and her staff completely unawares. The school athletic field obviously offers no shelter save the flimsy bleachers, but Lauren, thinking quickly, herds the students, teachers, and chaperones into the nearby cemetery, where the headstones might afford some protection even if the surrounding fence has no chance of standing up to a charging Lincoln. At the very least, the tombs are crowded on each other much too densely to grant the Murdermobile’s driver a straightaway of sufficient length to build up any serious speed. Yet to the great surprise of everyone cowering behind the gravestones, no practical test of their defensive value is ever made. The car stops dead outside the open cemetery gates, where it then remains poised at the entrance, alternately revving in place and turning tight, frantic circles like an enraged animal. What it does not do is cross the threshold to press the attack, nor does its driver emerge from behind the wheel no matter how venomously Lauren taunts him. One might justly ask what Lauren thinks she’s going to accomplish by taunting a homicidal psychopath, but she knows what she’s doing. By luring the killer out of his vehicle, she hopes to give Margie a chance to run for help. Naturally his refusal to rise to the bait makes Margie’s eventual breakout a nearer thing that she would have liked, but the teacher does indeed manage to reach safety and contact the police.

Wade and his men have some surprises in store for them, though, when they swoop down on their mysterious nemesis. The Murdermobile’s shocking speed and maneuverability might be attributed to its many obvious modifications. Wade’s inability to shoot out its tires and windshield with his sidearm might be explained away by self-sealing inner tubes and armor glass. His failure to see the driver even when the window was partly rolled down might be blamed on unfavorable lighting conditions. The ominous wind that now seems to precede the car everywhere it goes might be chalked up to coincidence. But there is simply no rational accounting for the driver’s ability to slip into and out of a lateral roll at will, or for the car’s ability to emerge unscathed from a fiery head-on crash. Luke is the first to resort openly to an irrational accounting, suggesting that the car kept out of the graveyard that afternoon because it or its driver was unable to trespass on consecrated ground. Nobody wants to follow Luke’s line of reasoning toward its logical conclusion, but they’ll realize soon enough that they haven’t a lot of choice in the matter.

It takes brass balls to ask an audience to buy a premise like the Devil’s hotrod. I’m not quite sure what it takes to actually seal that deal, but whatever it is, the makers of The Car definitely brought it. The astonishing thing about this movie is that it isn’t a joke, even though it clearly was not intended in jest. By any sane reckoning, The Car ought to be in the same league as Night of the Lepus, but instead it’s a taut, efficient, and effective fright film. The George Barris custom shop surely deserves a sizable share of the credit, for the transformation wrought on that old Mk III (a pretty stuffy car even in the eyes someone who harbors great affection for 1970’s land-yachts) puts it in company with the Amityville Horror house and the haunted theater in The Last Warning as an example of inanimate objects that project the illusion of purposeful intelligence. The Murdermobile looks both sentient and malevolent, with its oversized headlights mounted beneath horizontal folds of sheet metal like a pair of glowering eyebrows, and its heavily tinted windshield deflecting the viewer’s attention from the passenger compartment toward that face-like front end.

A well-crafted monster (which, after all, is what the Murdermobile really is) is frequently insufficient to save a movie from a preposterous premise, however— just look at Spawn of the Slithis! That’s where direction and writing come in. The Car benefits from something almost without parallel among other non-satirical Jaws copycats, a director who paid attention to the movie he was copying, and drew the right lessons from it. And while he was at it, Elliot Silverstein looks also to have studied that other triumph of Steven Spielberg’s early career, Duel, with equal diligence. Every cut, cue, and camera angle here is in the right place at the right time to perform a job that needs doing; every suspense-building trick is astutely selected and smartly deployed. Even a few nearly subliminal details are spot on, like the fact that the school marching band doesn’t play very well. As for the script, it’s much tighter and more solidly constructed than I’m used to seeing in a movie with three credited writers, strongly compensating for the wobbly performances of most of the lead players. Again correctly applying the example of Jaws, Michael Butler, Dennis Shyrack, and Lane Slate have gone out of their way to create a believable small-town milieu. We see almost at once that everyone in this place knows everybody else, and that those shared histories color everything the characters do, think, and feel. The writers do it with admirable economy, too, so that The Car never gives me that “Shut up and get on with it!” feeling that I always get from The Birds. Beyond that, a couple of the “shocking” turns this story takes really are fairly shocking. (Unless, of course, you’ve seen the trailer, which blithely blows the best surprises. Seriously— don’t watch the trailer first if you get the DVD.) And there are as many cleverly placed little details in the script as there are in its execution, such as the moment when the demonic car deliberately spares Amos Clements, evidently in order to let him go on contributing to the net evil content of the cosmos by regularly abusing Bertha. All told, The Car exhibits a standard of fit and finish that is wholly absent from most conventional Jaws wannabes, like Tentacles or The Deep Blue Sea. I wish it had a better cast, and a key element of the climax is telegraphed much too crudely from too early on, but this is still a stunningly good use of some stunningly inauspicious material.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact