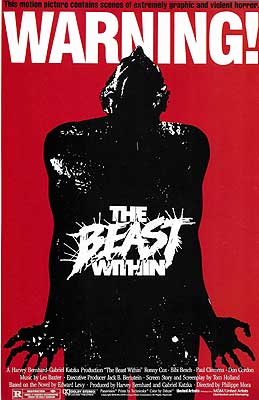

The Beast Within (1982) **½

The Beast Within (1982) **½

The early 80’s were good years for lycanthropy. The threefold special effects revolution of foam latex, cable-controlled animatronics, and air-bladder makeup prosthetics— all technologies that reached maturity circa 1980— made it possible for the first time to depict the transformation from human to animal (or whatever) as a physical, corporal process, bringing a sudden end to 45 years of yak hair and lapse dissolves. The Howling and An American Werewolf in London got the ball properly rolling (although they each took some cues here and there from Altered States), and within a year or so, seemingly everybody wanted in on the newly invigorated werewolf business. Nor was it just werewolves, either. Paul Schraeder made a new version of Cat People. Conan the Barbarian turned James Earl Jones into a snake. And a whole generation of off-brand monsters took and abandoned human form in ways more gruesome than had ever been seen before. The Beast Within falls into the latter category. This bizarre and baffling horror film is the closest thing I know of to a were-cicada movie, although the creature into which its protagonist gradually turns doesn’t bear those noisy but inoffensive insects much bodily resemblance. Rather, The Beast Within takes its marching orders from the periodical cicada’s life cycle, positing a sex-crazed monster that manifests itself at seventeen-year intervals and emerges from its host’s body by splitting open the skin of his back and climbing on out.

One night in 1964, near the little Mississippi town of Nioba, Eli (Ronny Cox, of RoboCop and Total Recall) and Caroline (Bibi Besch, from Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan and The Pack) MacCleary get stranded in the woods when their car breaks down. It’s a little-traveled road the MacClearys are on, so Eli sees nothing for it but to hike back into the village in search of a pay phone or a repair garage, whichever presents itself first. Caroline stays behind with the stricken vehicle, which turns out to be an extremely bad idea. There’s some sort of rape monster roaming the forest, and it has its way with her very thoroughly by the time her husband returns with a tow truck. Caroline survives the ordeal, however, and when she gives birth nine months later, she and Eli alike try hard to convince themselves that the baby is his. Since little Michael lacks a chitinous exoskeleton and is no more covered in slime than any other newborn, it seems a fair enough supposition at first.

However, when Michael (now played by Communion’s Paul Clemens) turns seventeen, he suddenly comes down with a serious illness that doesn’t match up with any known pathogen. After fruitless weeks of subjecting the boy to ever more exotic tests, his doctors begin thinking in terms of congenital conditions. Testing for those will mean combing through the medical histories of both parents and their forebears, and that at last forces the MacClearys to face the possibility which they’ve so determinedly ignored these seventeen years. If Michael is to have a chance at recovery, Eli and Caroline will need the medical history of the man who raped her. Man, you ask? Well, Eli never actually saw the creature, and Caroline has plausibly convinced herself that her impressions of an inhuman attacker must have been the result of the darkness, the disorienting circumstances of the rape itself, and her keyed-up emotional state both during and after the event. So leaving Michael at the hospital, the couple head back to Nioba to hunt up anything that might lead them to their son’s other possible father.

What they find is a town full of suspicious weirdoes. Edwin Curwin (Logan Ramsey, from What’s the Matter with Helen? and The Devil and Miss Sarah), who runs the local newspaper, is content to let Caroline dig through the old backfile, but only on terms that seem calculated to prevent her from finding anything. The keeper of the town archives flat stonewalls the MacClearys, claiming that she can’t do anything for them without the say-so of Nioba’s district court judge (apparently the closest thing to a government that exists around here). And Judge Curwin (Don Gordon, of Slaughter and Exorcist III)— who is indeed related to Edwin over at the paper— denies that there are any records to release for a supposed 1964 rape case. A visit to Sheriff Pool (L. Q. Jones, whom we’ve encountered before as producer of The Witchmaker and The Brotherhood of Satan) is no more concretely helpful on the subject of Caroline’s rape, as he was not yet in office back then, while his predecessor in the position is long dead. Nevertheless, Pool at least doesn’t convey the impression that he’s out to hide something. And when the MacClearys ask him about a story Caroline found during the course of her research— something about the murder of a man named Lionel Curwin (so many Curwins in this town!) right around the night she was raped— Pool confides quite a lot that the paper left out. Not content to kill Lionel, his assassin ate part of his body and then burned his house to the ground! The now-dead sheriff and his men never did catch the son of a bitch who did it, either. That’s about when Edwin discovers the page torn out of the bound backfile volume that Caroline left on the table where she was working, and calls the judge. Evidently neither man is in any hurry to have people talking about their relative’s ghastly demise again— or to have them uncovering some chain of events surrounding it which they’ve thus far been able to keep secret.

Meanwhile, back home, Michael is troubled by strange nightmares that somehow seem directly relevant to his parents’ investigation in Nioba. He dreams of a dilapidated farmhouse from which someone or something in the locked cellar whispers to him to be let out. Nothing overtly threatening or horrible occurs in these dreams, but the whole environment of the house feels ineffably wrong and twisted. When dream-Michael at last finds the locked trapdoor to the cellar and opens it, his real self awakens in some kind of fugue state. Seemingly directed from someplace deep in his subconscious, Michael gets dressed, sneaks out of the hospital, and hitches a ride to Nioba, where he drops in on (would you look at that…) Edwin Curwin. The newspaper editor takes Michael for a delivery boy from the grocery store (one of which did just drop off a parcel on Curwin’s front porch), and invites him in for a bite to eat. Michael takes that rather differently from how Edwin meant it, though. Instead of joining Curwin in a hamburger, he helps himself to about a quart of his host’s blood! Then he wanders off and passes out in front of the house where Amanda Platt (Katherine Moffat) lives with her grouchy, violent, and intensely misogynistic father, Horace (John Dennis Johnston, from Streets of Fire and KISS Meets the Phantom of the Park). Amanda calls 911, and soon Michael is confined to a new hospital, under the care of Dr. Schoonmaker (R. G. Armstrong, of Race with the Devil and Children of the Corn).

Eli and Caroline are understandably weirded out by their son’s nocturnal arrival in Nioba, even if nobody has linked him yet to the murder of Edwin Curwin. The discussion over Michael’s hospital bed the next morning turns heated, and the boy oddly blurts out, “You’re not my father! Billy Connors is my father!” He’s unable to explain what he meant by that a moment later, though, and claims to have no more idea than Eli who Billy Connors is supposed to be. Equally beyond Michael’s power to explain is the strength of his sudden attraction to Amanda— although it surely is suggestive when the girl mentions that her dad descends from a distaff branch of the Curwin family. That information comes out during a stroll the kids take together in the woods (this time, Michael didn’t need any mysterious trance to make him slip away from his caretakers), the romance of which is rather spoiled when Amanda’s dog digs up a severed human forearm from the boggy ground.

Sheriff Pool, investigating the dog’s discovery, is horrified to learn that the soggy stretch of the woods around Nioba is practically one enormous mass grave. There are dozens of bodies out there, in sufficiently varied states of decay to indicate years’ worth of illicit burials. And worse yet, most of the remains show some sign of having been gnawed on. Sound like the work of Lionel Curwin’s un-caught killer to you? Then closer examination of the bodies turns up evidence that at least some of them were not murder victims but grave-robbing trophies, dug up from the local cemetery, partially eaten, and finally reburied in the forest. That gives Pool the idea that he ought to have a chat with Dexter Ward (Luke Askew, from The Warrior and the Sorceress and Dune Warriors), who runs Nioba’s funeral parlor. Ward claims to know nothing of what must have been a massive and sustained spree of grave violations, and Pool comes away thinking he might not quite be telling the truth. The sheriff is probably right, too, given that Ward is the next person Michael kills in one of his trances. Also on the menu is a childhood friend of that Billy Connors guy whom Michael said was his father before, an Indian by the name of Tom Laws (Ron Solle, of Pterodactyl Woman from Beverly Hills). The connection between Laws and the mysterious Connors might be the most important detail of the story thus far, because bullshit Indian magic is the only thing that even begins to make sense of the revelations of the final act, when Judge Curwin finally gets scared enough to come clean about the secret he’s been keeping since 1964.

As you’ve probably guessed already, Connors and the rape monster were the same “person,” and it was also Connors who killed Lionel Curwin. Suffice it to say that he had a really good reason, and that that reason also explains all those half-eaten corpses buried in the woods. Raping Caroline, meanwhile, was Billy’s way of arranging his reincarnation so that he could extend his vengeance to Lionel’s whole family. Evidently there hadn’t been time for that back in ‘64, I guess because cicadas don’t live very long as adults. I’d like to tell you how cicadas and cannibalism and family vendettas and soul-transference via monster rape fit together, but the truth is that they don’t really. The best I can do is to suggest to you that The Beast Within is maybe less a film about weird-ass lycanthropy than it is one about a weird-ass wendigo.

It’s the nonsensical solution to the mystery that really hurts The Beast Within. The individual horrors on offer here are extremely strong: cannibalism, grave-robbing, torturous captivity, hillbilly corruption conspiracies, woodland rape monsters, a boy compelled against his will to murder the enemies of a man who died before he was even born, the hideous and painful-looking transformation that finally deprives Michael of his humanity. And so long as we have no idea what all these disparate monstrosities have to do with each other, they’re strong in combination as well. The Beast Within’s creators have mastered a technique more often associated with Italian horror films of the 70’s and 80’s, offering up a fever dream of eye-catching affronts against reason and sanity. Unlike the typical spaghetti-splatter opus, however, this film features characters whose motives we can understand, and whose behavior follows logically from them. That contrast between rational people and profoundly irrational circumstances makes The Beast Within the kind of can’t-look-away cinematic nightmare that comes along all too infrequently— until the explanations begin. Then it all falls right the fuck apart, leaving the viewer with the bad kind of unanswered questions. For starters, what’s in it for the conspirators? The relative thicknesses of blood and water notwithstanding, what in the hell could account for their willingness to cover up crimes as vicious and depraved as Lionel Curwin’s? Meanwhile, are we supposed to believe that Indians just sort of have magic in their DNA? Because Laws and Connors both seem pretty thoroughly assimilated to Western ways, and it hardly seems likely that the latter could have studied up on how to command the spirit world while he was imprisoned in Lionel’s cellar. And for the love of Khepri, why a cicada? Of all the North American wildlife that could have set the behavioral and life-cycle pattern for this peculiar version of the wendigo, why those utterly tame and innocuous insects? And if that’s really what we’re going with, then why not have the monster suit resemble a cicada in some way, rather than just being generically ugly and slimy? Most perplexing of all, why synthesize an unconvincing electronic version of the cicada’s instantly recognizable chirr to play over the Michael-as-monster scenes, when you could just walk out into the damn woods with a tape recorder on any day of the summer and catch the real thing?

Another questionable choice made by this movie’s creators concerns its character focus. There’s a reason why most lycanthropy movies up until recently have tended to focus on the plight of the were-critter him- or herself. Loss of control, loss of identity, loss of self-knowledge— these are all terrifying things, and The Beast Within is set up so that Michael suffers from all of them. He’s therefore the obvious candidate for the protagonist of this movie, so it feels like a bit of a waste when instead he’s mostly just a passive object to which the story happens, and whose own perspective we never really experience. At the same time, though, a parent’s fear for a child laid low by some inexplicable, unknown ailment is pretty formidable stuff, too. The terror of impotence before an uncaring universe doesn’t come much more concentrated than that, so Eli and Caroline do have a pretty good claim on the spotlight. Ronny Cox and Bibi Besch are also way better actors than Paul Clemens, so maybe the filmmakers made the right decision after all. In any case, The Beast Within is pretty lumpy and malformed, but it’s one of those rare films that are worth watching for their potential alone, imperfectly realized though it may be.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact