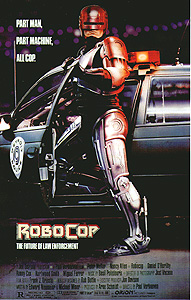

RoboCop (1987) ****

RoboCop (1987) ****

I saw RoboCop for the first time in the theater, when it was new, while people were still arguing about it. This was Dutch director Paul Verhoeven’s first movie for a major American studio, and like practically everything he would do in Hollywood subsequently, it pissed off a lot of people. By 1987, US audiences— and US media critics even more so— were fairly deep into another of their periodic mood swings over pop-culture violence, reacting against the glut of bloodshed and destruction that had characterized entertainment in nearly all media during the first half of the decade, and pointing to it as an easy scapegoat to explain the equally massive glut of real-world bloodshed that swept the decaying hearts of America’s post-industrial cities during the second. In such a climate, it was only to be expected that an outwardly nihilistic spectacle of baroquely gory action like RoboCop would be singled out for special censure. Not only was this probably the most carnage-intensive mainstream movie since Conan the Barbarian, but it also aggressively flouted what was by then about a three-year trend away from such things; much like the contemporary Hellraiser, RoboCop seemed to say, “Fuck all you sissies— we’re taking this to a whole new level!” The irony is that, in a way, RoboCop was as much a part of the anti-violence backlash as it was an act of defiance against it, for through this film, Verhoeven offered a contemptuous critique of the recently concluded vogue for exploding limbs and bloody mutilations even as he catered to the most extreme tastes of those who weren’t ready for it to be over yet.

Appropriately enough, RoboCop is set in Detroit, one of the most thoroughly blighted of the nation’s former industrial metropolises, and a byword for crime, despair, and social breakdown in 1987. Things have not gotten much better in however many years are supposed to have elapsed since then. Although it is encircled by the affluent suburbs and prosperous corporate directorates of New Detroit to the south and east, Old Detroit is a cesspit fit only to be evacuated and torn down. The head of Omni Consumer Products (Dan O’Herlihy, from The Cabinet of Caligari and The Last Starfighter) has a plan to do just that with his massive Delta City redevelopment project, but before anything can be done in that direction, somebody is going to have to figure out how to get a handle on Old Detroit’s rampant crime problem. The police are so thoroughly outmatched that Clarence Boddicker, the crime lord of Old Detroit (Kurtwood Smith, of Fortress and Deep Impact), is believed to have killed at least 31 cops personally. OCP has a couple of cards still to play, however. First, the company currently holds the management and supply contract for the city’s police department; secondly, its Security Concepts division has two projects in the works that promise to turn the tide in the battle against crime, both effectively and profitably. (After all, if OCP runs the police department, its bosses can easily order the cops to put out a no-bid contract for whatever Security Concepts sees fit to offer. It has all the benefits of racketeering, but it’s all perfectly legal!) At the next OCP executive meeting, Dick Jones, the chief of Security Concepts (Ronny Cox, from Deliverance and The Car), presents the prototype of the Series 209 Enforcement Droid. About the size of a subcompact car, armored against small-arms fire, and equipped with multiple heavy-caliber machine guns and triple-barreled launchers for rocket-propelled grenades, the ED-209 certainly won’t have anything to fear from even the most well-supplied street criminal, and as a fully autonomous, artificially intelligent machine, it can keep working hours that no human cop could sustain. Unfortunately, the ED-209 also has something of a one-track mind. When Jones hands one of his fellow executives a pistol to point at the robot in order to demonstrate its arrest protocol, the machine opens fire even after he complies with its command to disarm— and keeps firing until there’s nothing much left of the luckless exec but a heap of unrecognizable meat. The big boss is not amused. He orders ED-209 to the back burner, and shifts priority to the RoboCop project, brainchild of Jones’s ambitious young rival, Bob Morton (Miguel Ferrer, of DeepStar Six and Star Trek III: The Search for Spock). Morton believes RoboCop will be ready to go to prototype within 90 days, just as soon as he can secure a volunteer.

Meanwhile, Officer Alex J. Murphy (Peter Weller, from Screamers and Of Unknown Origin) receives a transfer from the cushy Metro South precinct to the hellish Old Detroit warzone of Metro West. Reed (Robert DoQui, of Coffy and My Science Project), the Metro West desk sergeant, pairs Murphy with Anne Lewis (Nancy Allen, of Carrie and Poltergeist III), one of his toughest veterans, and sends them out to familiarize Murphy with his new beat. It’s a pretty steep learning curve they have there in Metro West— here it is Murphy’s very first day on the job, and already he winds up intercepting a bank heist led by the infamous Clarence Boddicker. Murphy and Lewis trail Boddicker and his gang to an abandoned steel mill, but the attempt at their capture accomplishes nothing but to get Lewis knocked unconscious and Murphy shot literally to pieces by Boddicker’s men.

Now, you remember when I said Morton was seeking volunteers for his RoboCop program? Well, it turns out that really meant he was waiting for some cocky schmuck like Murphy to get himself killed so that the Security Concepts eggheads could rebuild whatever was left of him into a nearly invincible cyborg to do the same job as ED-209, only many times as effectively and for a fraction of the cost. A couple of months after Murphy’s demise, Morton shows up at Metro West with a staff of OCP technicians, and introduces Reed and his people to their new heavy artillery. Morton didn’t keep anything of Murphy from the neck down but internal organs, and most of the “dead” man’s face is concealed within RoboCop’s Kevlar-laminated titanium headpiece, so he ought to be unrecognizable to his former coworkers. And because Murphy’s brain has been reconfigured and his memories suppressed, he shouldn’t be able to recognize any of them, either. Lewis, however, begins to suspect the truth almost immediately, for she notices that the cyborg shares a few very distinctive mannerisms with her tragically short-lived partner.

RoboCop certainly lives up to Morton’s expectations, making a noticeable dent in Old Detroit’s crime rate in a matter of weeks. Needless to say, that success does nothing to improve his relationship with Dick Jones, who now begins looking for any means of reasserting himself over his rival, legal or otherwise. Meanwhile, evidence begins surfacing to the effect that Morton’s minions didn’t do nearly as thorough a job of effacing Murphy’s memories as they thought. RoboCop relives Murphy’s murder in his dreams, even though he was not really believed to be capable of dreaming in the first place, and when he responds to a hold-up at a gas station, he recognizes the perpetrator (The Blob’s Paul McCrane) as one of the gunmen who haunt his subconscious. A session with the precinct computer identifies the robber as Emil Antonowski, Clarence Boddicker’s right-hand man, and supplies all the names and identities of those believed to constitute the core of Boddicker’s organization. RoboCop/Murphy begins pursuing a private vendetta against Boddicker, and when he discovers that the crime boss is on the take from Dick Jones, that leads him eventually into conflict with his own creators.

I have no idea to what extent this was deliberate, and to what extent it was just dumb luck (although their subsequent track records might be taken to suggest the latter), but RoboCop shows screenwriters Ed Neumeier and Michael Miner to be remarkably astute futurists. In their script here, they predicted several important trends of the succeeding twenty years: the for-profit privatization of traditional public-sector services like law enforcement, and the corruption attendant thereupon; the predatory gentrification of distressed urban areas where populations have declined to a relative handful of the truly down and out; the marked turn for the bloodthirsty and draconian that public opinion would take after two decades of escalating crimes rates peaked in the late 1980’s— even the consumer rebellion against the ever smaller, ever thriftier, ever more underpowered cars that increasingly dominated the automotive market beginning in 1977. I can think of very few sci-fi movies whose visions of the future are as eerily prescient as RoboCop’s. In contrast to most other films of its type, RoboCop has only become more credible with the passing of time, even if its central premise remains as fanciful as it ever was.

The production design helps a lot with that, too. Whereas most sci-fi movies set in the future create the look of their fictional worlds more or less from scratch, RoboCop’s design esthetic is in most respects firmly grounded in design trends that were already at work in the 1980’s. New Detroit, for the most part, is really Dallas, Texas, which had recently undergone a major construction boom, adding a number of impressive, state-of-the-art office towers to its skyline. The police cruisers are simply Ford Tauruses (easily the most futuristic cars on the road when they were introduced for the 1986 model year) with modified headlights— and subsequent years really did see the widespread adoption of the Taurus by police departments around the country. The transition from revolvers to semi-automatic pistols as standard police sidearms was already underway, as was the introduction of Kevlar body armor, and even RoboCop’s daunting machine pistol was just a slight redress of a real-world firearm, the Beretta Auto-9. Materially as well as sociologically, the future we got wound up looking a lot like the one this movie’s creators envisioned.

But to return to what I was saying at the beginning of the review, although RoboCop made its greatest impact at the time through the controversy over its wildly excessive graphic violence, it becomes clear upon close examination that Verhoeven’s aim was largely to poke fun not only at the very sort of movie he was making, but indeed at the entire culture that could produce the likes of it. The delivery may be mostly deadpan, but the material itself is often so arch that the intent is difficult to miss. Watch the scene in which the TV news reports RoboCop visiting an elementary school and admonishing the assembled children to “Stay out of trouble,” then think back to those “Knowing is half the battle!” PSAs that concluded every episode of the “GI Joe” cartoon series from 1984 to 1986. For that matter, take a close look at the montage of worldwide disaster footage that opens the news program whose broadcasts serve as act breaks throughout the film, together with its ludicrous slogan (“You give us three minutes, and we’ll give you the world!”), and consider that the mid-80’s were when the pestilent tabloidization of television news really hit its stride. Compare the macho triumphalism of RoboCop’s debut battles with the similar tone of contemporary vigilante movies like Death Wish 3, or the fate of Emil Antonowski with about three out of every five non-slasher horror movies of the time. (Indeed, the latter wouldn’t be out of place in a Troma Team production.) And while the main template for the unnamed asinine sitcom featuring the “I’ll buy that for a dollar!” guy was reportedly “The Benny Hill Show,” what it reminds me of most is the inexhaustible army of catchphrase characters that, by 1987, had transformed “Saturday Night Live” from a fitfully amusing exercise in absurdism and the comedy of lawlessness into a top contender for the title of Most Resolutely Stupid Show on Television. Verhoeven is holding a funhouse mirror up to the boorishness of 80’s America, and having a good laugh at both the bluenoses who don’t get the joke and the boors who don’t understand that the joke’s on them.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact