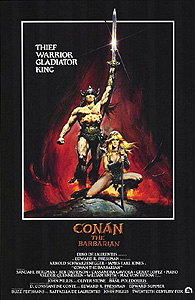

Conan the Barbarian (1982) ***½

Conan the Barbarian (1982) ***½

Heroic fantasy was pretty much extinct as a cinematic genre by the early 1980’s, and had been for a good fifteen years or so. True, it wasn’t until 1974 and 1977 respectively that the second and third Ray Harryhausen Sinbad movies arrived on the scene, and there were those Tolkien cartoons produced by Ralph Bakshi and Rankin-Bass in 1978, but that had been just about it since the long-ago day when Kirk Morris and Reg Park had hung up their loincloths for good back in the mid-1960’s. This is really very strange when you think about it, because the 70’s were a boom time for such things in the various print media. Tolkien, of course, had his legions of flower-child devotees, writers like Anne McCaffery and David Eddings were crawling out of the woodwork, and Gary Gygax was busy inventing Dungeons & Dragons. The sweaty, testosterone-soaked fantasy of the pulp era was enjoying a renaissance, too; new editions of the Edgar Rice Burroughs serials were cropping up left and right, and you couldn’t swing a double-handed war-axe in a bookshop without chopping into several dozen paperback novels featuring cover art painted by Frank Frazetta. Then there was Heavy Metal magazine, which also came into existence during this period, dividing its attention just about evenly between the work of mostly European artist/writers who obviously saw themselves as heirs to the pulp tradition and drug-inspired tales about space-traveling hippy nudists. (And come to think of it, a damned lot of Frazetta-style artwork showed up there, as well.) But most importantly for our present purposes, the 70’s saw a big revival of interest in the writing of Robert E. Howard.

Howard, in retrospect, was one of the big boys of the Weird Tales generation, though like H. P. Lovecraft, he was not greatly appreciated during his lifetime. And in Howard’s case, we’re talking about a short lifetime indeed— he put a bullet through his brain in 1936, when he was only 30 years old. But in the brief span of his career, he wrote stories and created characters the influence of which is still being felt today. The most famous of these figures was a wandering barbarian brigand chieftain by the name of Conan, who lived during what Howard called the Hyborean Age, the period between the sinking of Atlantis and the beginning of recorded history. You’d never guess this from looking at the shelves of a used book shop that specializes in fantasy and sci-fi, but Howard sold only seventeen Conan tales for publication before his suicide; the vast bulk of the Conan material available today was written by various anonymous hacks (and a few big-name hacks like L. Sprague De Camp and Lin Carter) long after Howard’s suicide, and up until recently, what little original Howard material featuring the character exists was virtually impossible to find except in sanitized, bowdlerized, or otherwise vandalized forms. (It’s difficult to name another writer who has been so ill-served by his so-called admirers.) But be that as it may, Howard— and Conan— were big deals in the 70’s, to the extent that even squeaky-clean Marvel Comics cut a deal with the managers of his estate. Marvel’s Conan the Barbarian started publishing in October of 1970, and didn’t finally die off until 1996, spawning at least two spin-off titles while it lasted. Other Howard heroes like Solomon Kane showed up in the Marvel Universe, too, although it’s doubtful whether their creator would have recognized them. (At one point, Marvel went so far as to send Kane to Transylvania for a showdown with Count Dracula!) That kind of critical pop-cultural mass never goes unnoticed for long in Hollywood, so it was really only a matter of time before Conan would make the jump to the big screen, touching off a full-scale resurrection of the venerable barbarian film.

The first stirrings of Conan the Barbarian, the movie, look to have been made as early as 1978, but it ended up being a very long gestation period. The first version of the screenplay— written by, of all people, Oliver Stone— moved Conan from Howard’s prehistoric Hyborian Age to some kind of post-apocalyptic future. I’m guessing a movie made from Stone’s draft would have ended up looking a lot like the contemporary “Thundarr the Barbarian” cartoon, which while certainly an amusing notion, would have made lots of people very angry. Fortunately, director John Milius was rather more level-headed than that, and he rewrote Stone’s screenplay so as to put it back into its proper temporal context. Then, with $17 million of Dino De Laurentiis’s money and a will as indomitable as that of Conan himself, Milius set about bringing tangible life to a world that had previously existed only in the imagination of a long-dead malcontent. And though the critics mostly didn’t think so at the time, I’d say he did a damn good job of it.

Milius’s version of Conan: The Early Years is quite a bit different from the “official” story recognized by the print material. Somewhere in the snowy forests of the far north, a man of the Cimmerian tribe (William Smith, from Invasion of the Bee Girls and Maniac Cop) forges a beautifully worked sword. (Ye gods! This opening credits sequence makes swordsmithing look like just about the coolest, manliest occupation in the world!) When he’s finished, the Cimmerian takes his son, Conan, up onto a hilltop, where he relates his people’s myth explaining how an otherwise quite backward culture came to possess the necessary knowledge for making steel weaponry. Once there were giants in the Earth, the man says, and they tricked Crom, the god of the Earth, into giving them the secret of steel. When Crom realized what the giants had done, he and the other gods went to war against them, and exterminated them all. But in the heat of the moment, the gods forgot what they were fighting for, and when they returned to their homes, they left the secret of steel lying unclaimed on the battlefield, where men could find it. Conan’s father then tells him that steel holds a mystery which a man must solve, for steel is central to a Cimmerian’s life: “Nothing in this world can you trust— not men, not women, not beasts— but this [he says, holding up his snazzy new sword]... This you can trust.”

Or maybe not. A day or two later, the Cimmerians’ village is overrun by pillaging hordes on horseback, riding and fighting under a standard that depicts a snake with heads at both ends coiling up to face each other over a black sun and a black moon. Valorous though they may be, the Cimmerians are no match for the invaders, and one by one they fall until there is not an adult man left alive in the village. The leader of the raiders (James Earl Jones) takes Conan’s father's sword, and uses it to decapitate his mother while the boy watches. Conan and all the other children are then packed off to a life of slave labor in a land far to the south.

This is the point at which Conan the Barbarian stops making much in the way of sense for a couple of reels. The Cimmerian children are all put to work pushing some kind of huge grinding wheel, perhaps a mill for grain. Give me some time, and I bet I could think of about 15,000 more efficient uses for two dozen slave-boys and a comparable tally of more efficient ways to grind flour. Day in, day out, for something on the order of fifteen years, Conan marches around in circles pushing that stupid wheel. And with each dissolve indicating the passage of time, he has fewer fellow slaves to assist him (I always kind of figured the other kids were worked to death, but who really knows?), until in the end, he is left pushing the thing all by himself. Naturally this life of hard labor has caused Conan to grow up freakishly big and strong, and when the plot resumes its forward motion at last, we see that he is now being played by Arnold Schwarzenegger. Damn. I'd forgotten just how grotesquely overdeveloped old Arnold was back in the day! I’m apparently not the only one who is impressed by that grotesque overdevelopment, either, because the adult Conan is soon bought (I think— this section of the movie is maddeningly, pointlessly vague) by another big man with a bushy mane of red hair (Luis Barboo, from The Bare-Breasted Countess and Return of the Blind Dead), who presses him into service as a pit-fighting gladiator. Conan, whose combat training is presumably limited to whatever his father had a chance to teach him back when he was a lad, nevertheless kills every man who is put up against him, his stunning victories making his new owner one wealthy individual. Eventually, Conan’s master realizes he’s got more than just a world-class pit fighter on his hands, and he takes the Cimmerian with him to the East, where (in the words of a narrator whom we won’t be meeting in person for a good, long while yet) “the war-masters [teach] him their deepest secrets.” And because this is the Orient we’re talking about, training in the martial arts comes as part of a package deal that includes studies in poetry and philosophy (and the literacy necessary to conduct those studies). After his schooling is completed, the Red-Haired Guy starts hiring Conan out as a mercenary in the armies of the neighborhood steppe warlords. This goes on for... well, who knows how long?... until one night when Conan’s master sets him free— for absolutely no reason that I can fathom. I suppose it's just barely possible that the Red-Haired Guy was drunk at the time, as Barboo does seem to be slurring his lines just a bit, but really I think Milius just got lazy. In any case, Conan runs off across the steppe, where a pack of wolves chases him to what turns out to be the tomb of some ancient king. Seeking shelter inside, Conan sees the long-dead monarch still seated on his dusty throne, gripping a sword clotted with rust and cobwebs. Remembering the myths of his people, Conan gets it into his head that he’s stumbled upon the subterranean hall of Crom himself, at which point he takes up the sword and reverently sets about rehabilitating it. Those wolves are going to have a fight on their hands tomorrow morning...

You might think that’s the signal for the real story to begin, but to do so would be overly optimistic. It’s coming up soon, but we’ve still got a little more setup to get through. Conan’s wanderings bring him to a hut situated in the shadow of some oddly formed hills, where he meets a strange woman (Cassandra Gaviola, from The Black Room and The Amityville Curse), who offers him hospitality. Once the barbarian is inside, his hostess begins babbling about how his arrival in the area was prophesied— a mighty conqueror from the north who would one day make himself king and “crush the snakes of the Earth.” The mention of snakes gets Conan thinking about the standard under which the raiders who destroyed his village fought, and he asks the woman if she knows what it is. She does, but the information will come at a price; luckily for Conan, that price is merely to go to bed with her. Then again, since she turns into some kind of vampire thing while the two of them are fucking, maybe that price is a little steep after all. At least she has the decency to tell Conan that he will find what he’s looking for in Zamora, “the crossroads of the world,” before she grows fangs and forces him to start handing out beat-downs.

The next morning, Conan realizes that the vampire woman had a prisoner. The wiry little Mongol whom she had chained up in the back yard introduces himself as Subotai (professional surfer Gerry Lopez), and says that he is an archer and a thief. More importantly, he also knows the way to Zamora, and so Conan releases him to become his traveling companion. Conan’s arrival at the old city marks his first brush with civilization, and he is a little overwhelmed at first. But when his questioning of the locals turns up the information that the cult of a foreign snake-god called Set has recently come to dominate the religious life of Zamora and its hinterland, the Cimmerian settles down a bit. This, after all, might have something to do with those long-ago horsemen. Then Subotai learns that the Tower of the Serpent, the temple of Set, is said to house a fabulously valuable jewel, and the two adventurers hatch a scheme to infiltrate the tower and make off with the treasure while attempting to determine whether these snake-worshippers are connected to the destroyers of Conan’s home. It is while setting off on this exploit that they meet Valeria (Hell Comes to Frogtown’s Sandahl Bergman, who is much better here than she would be in Red Sonja three years later). Like Conan and Subotai, Valeria is a thief— and like them as well, she’s trying to sneak into the Tower of the Serpent and help herself to the cult’s wealth. She and the men join forces, and the raid turns out to be a smashing success. Conan and Subotai have to kill a 40-foot snake to do it, but they seize both the Eye of the Serpent and a jade medallion carved into the exact likeness of the standard Conan remembers from his childhood. What’s more, the thieves strike so quickly that Rexor (Ben Davidson, from The Black Six and Behind the Green Door), the high priest of Set— whom Valeria identifies as being second only to cult leader Thulsa Doom— is completely at a loss even to retard their escape.

The raid on the temple marks the beginning of a lucrative and glorious partnership between Conan, Subotai, and Valeria. Their success brings them a steady flow of moderate wealth (which they naturally proceed to blow on boozing, doping, and screwing), their reputation as fighters and thieves to be reckoned with spreads throughout the land, and Conan and Valeria fall as deeply in love as a two people who only rarely speak are able to. Then one day, the three companions awaken from the stupor of last night’s carousal to find their camp surrounded by armed men. The soldiers haul them before King Osric (Max von Sydow, of Flash Gordon and The Exorcist), under whose authority the mostly lawless Zamora theoretically falls. To their surprise, Conan and his sidekicks are to face neither prison nor execution. Instead, Osric has heard of their accomplishments, and he has a job for them. Some time ago, his own daughter (Valerie Quinnesson, from Summer Lovers) fell in with the worshippers of Set, and because the sect is well known for, among other things, inducing children to murder their parents, the king is understandably eager to get her away from their influence. This is doubly so because Osric has heard that Thulsa Doom himself has taken a liking to the girl, and plans to add her to his personal harem. The king will pay Conan and his friends as much as they can carry if they will travel to Thulsa Doom’s Mountain of Power and steal back Osric’s daughter.

This ends up occasioning some soul-searching among the three thieves. Valeria (and, one suspects, Subotai as well) would prefer to take Osric’s money and run. If half the things said about him are true, Thulsa Doom is far too powerful for them to take on, and the success of their career in thieving has given them much to lose by taking so great a risk. Conan, however, is spoiling for a fight. That medallion he stole from the temple tells him that the road to revenge leads directly to the cult, perhaps even to its leader. At the same time, he sees the sense behind Valeria’s objections, and in the end, Conan compromises by sneaking away before dawn to rescue Osric’s daughter— and throw down with Thulsa Doom— alone, thus risking no one’s hide but his own. This is not one of Conan’s better ideas. Though he infiltrates a pilgrimage to the Mountain of Power, and even gets within striking range of Thulsa Doom (and yes— he’s James Earl Jones, alright), the jade medallion gives him away, and he is seized and beaten to within an inch of his life by Doom’s lieutenants, Rexor and Thorgrim (Sven-Ole Thorsen, of Predator and The Running Man)— both of whom, now that we see them without their priestly robes, are also familiar from the attack on Conan's village. (One does not swiftly forget a couple of guys who look like they ought to be playing bass for Celtic Frost or Venom, you know.) An impressively eloquent tongue-lashing from Thulsa Doom later, Conan is crucified on the Tree of Woe.

Just about the only good thing to come out of the whole trip, in fact, was Conan’s meeting with a strange little man who calls himself a wizard (Mako, whose agent surely deserves some sorcerous reprisal for getting him cast in Highlander: The Final Dimension and RoboCop 3), whom he befriends, and who reveals himself as the film’s narrator. When Subotai and Valeria come looking for Conan, they run across the wizard first, and his magic plays a role (just how big of a role is debatable) in saving the Cimmerian’s life after his friends rescue him from the Tree of Woe. And this, my friends, leads us to the official beginning of Clobberin’ Time. Conan and his allies will square off with Doom and his minions three times in rapid succession, and though not all of our heroes will live to see the closing credits, you can bet your ass it isn’t going to be the snake-lover who comes out on top.

I’d like to talk for a bit about Thulsa Doom at this point, because he is far and away Conan the Barbarian’s most intriguing character. He alone exhibits any dynamism or evolution, growing and changing enough for the whole cast. We first see him as a barbarian warlord, sweeping the Hyborian steppes on an obsessive quest for weapons of steel, which his own people presumably haven’t yet learned to make. But in the decade and a half of Conan's career as a slave, Doom turns away from his life of rapine to pursue a more spiritual sort of power. It is implied that the catalyst for the change was Doom’s eventual solution to the Riddle of Steel spoken of by Conan’s father— that the strength of steel lies not in the metal itself, but in the body that wields it, the mind that commands it, and the heart that motivates it. And indeed it is when he takes this lesson to heart that Thulsa Doom’s power truly begins to rise. There are many things left sketchy here that any attentive viewer will long to know in more detail, however, for Doom’s ascendancy happens entirely out of our sight. There are fascinating hints, for example, that he is not the founder of the of the cult of Set, but more of a Zarathushtra figure who seized upon an existing mythology and transformed it into a more vibrant spiritual force by rewriting or reinterpreting its dogma in a way that spoke more profoundly to his followers’ concerns. Then again, since we never get any idea of what the cult’s doctrines are, it is equally possible that Doom is less Zarathushtra than Jim Jones. Conan, for his part, certainly sees the situation in the latter terms, and it looks like he has the director’s sympathies. He’d probably have Robert E. Howard’s, too.

Just how much of Robert E. Howard ended up in Conan the Barbarian is open to debate. Certainly the character’s origin and life-history are completely different from what Howard wrote, while the Conan of Stone and Milius is in many ways not the same man as his literary model. For one thing, Howard’s Conan talked— although considering how obviously Schwarzenegger struggles with what little dialogue he has, that change makes a considerable amount of sense. The Conan of the pulps was also no trained martial artist; rather, he was a brawler who got by on instinct, sheer physical prowess, and a marked willingness to fight dirty. All the same, though, I think Howard would have approved of this Conan. Like the original, the movie Conan is first and foremost a creature of savagery and raw will. At one point, Valeria exhorts him, “let us grab the world by the throat and make it give us what we desire,” and that is precisely what he does— at least after he is released from the bondage in which he spends the first act.

It isn’t just the character of Conan that I think would please Howard in Milius’s rendition, either. For all the changes to the letter of the story, this movie captures the feel of Howard’s writing like none of the other spin-offs have. Whether he was writing about Conan, Kull, Solomon Kane, or whomever, Howard’s adventure stories had a gritty, bleak directness to them that has rarely been imitated with any success. Howard’s outlook was as primitively pagan as that of his heroes, and one can easily imagine him uttering Conan’s famous prayer from the lead-up to the climactic battle:

Crom... I’ve never prayed to you before— I have no tongue for it. No one— not even you— will remember whether we were good men or bad, why we fought, why we died. No. All that matters is that today, two stood against many; that is what’s important. Valor pleases you, Crom, so grant me one request: Grant me revenge! And if you do not listen, then to hell with you! |

For that reason, it is well that an utterly humorless, shamelessly retrograde macho-man like Milius should preside over the film adaptation. Subsequent barbarian movies—including the sequel to this one— would be far more light-hearted even at their crudest and most violent, but there is not a trace of camp sensibility in Conan the Barbarian. I once read an article which contended that the secret to Howard’s success was that he wrote as if he believed in what he was writing, and from the very beginning, when an epigram paraphrases Nietzsche, “That which does not kill us makes us stronger,” it is obvious that Milius believes too. It is a powerful testimony to his skill as a director that, even with an often shaky script and a cast made up mostly of non-actors, he can make his audience share in that belief, or at least want to. In this, it must not be forgotten, he has an indispensable ally in composer Basil Poledouris. Poledouris’s score is a literally constant presence in the film, and has such imposing and imperative personality that it can enliven even the most mundane scene— scrubbing a toilet bowl would look like an awesome and heroic undertaking if it were set to this movie's main theme! With the aid of Poledouris, Milius fixes it so you never notice that Conan the Barbarian is more than two hours long, and that at least a quarter of that time is devoted to people running, riding, hiking, or otherwise trekking across the scenic landscapes of rural Spain. And in the world of filmmaking, that is truly a deed fit for heroes.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact