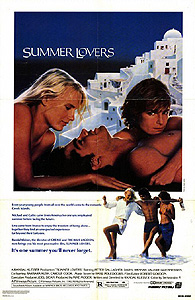

Summer Lovers (1982) **½

Summer Lovers (1982) **½

Sometimes being conventional is the weirdest thing a movie can do. Take Summer Lovers, for example. After “people who rightly detest each other fall in love for no discernable reason,” there may be no romance-story formula more deeply entrenched than “love lifts people out of a rut they never realized they were in,” and Summer Lovers hits all the expected beats therein. There’s the shy homebody who always fantasized about running wild, but never had the nerve to do it; the dedicated professional type whose aversion to commitment stems from an unarticulated fear of being hurt; the person in revolt against a creeping sense that their whole life has been planned out for them by others; the eccentric friend who saves someone at the last minute from making a terrible romantic mistake. It has the getaway to an exotic locale that sets the story in motion; the infidelity serving as a wake-up call to trouble in a couple’s relationship; the meeting with an exciting stranger that opens a protagonist’s eyes to new possibilities; the panicked retreat from those possibilities, culminating in a climactic reunion that ignores a host of troublesome complications for the sake of a happy ending. And along the way, it has oodles of joyful montages set to upbeat, overexposed pop hits. Exactly what you would expect from a Hollywood love story, right? Sure. But what you would not expect is for all those fossilized tropes to be deployed in an apparently sincere paean to polyamory.

Americans Michael Pappas (Peter Gallagher, from Brave New World and House on Haunted Hill) and Cathy Featherstone (Daryl Hannah, of Blade Runner and The Fury) arrive on Santorini, a beautiful volcanic island in the Aegean, for an eight-week vacation. The island forms an interrupted ring of steeply sloping ridges around a lagoon centered on the volcano’s cone (there must have been an incredible eruption a few thousand years back), and the couple’s rented villa, though of extremely modest dimensions, sits perched on one of its most scenic spots, high up near the crest of the largest arc-segment. We’re five minutes into this movie, and already I’m thinking, “Damnit— now I want to go to Greece for the summer!” Santorini, with its bustling discos, extensive nude beaches, and constant influx of free-spending European tourists, is not a place that encourages inhibitions, and it isn’t long before Michael begins chafing against Cathy’s under the island’s influence.

Now before we go any farther down that road, let’s take a moment to consider this couple, and to examine the state of their relationship. Michael and Cathy have been dating for five years, but they’ve known each other twice that long. At their age, that means they must have gone to elementary school together. Cathy is extremely conservative by temperament, suspicious of change per se and highly averse to taking any kind of risk. She’ll admit at one point that she’s worn her hair the same way since she was twelve years old, and when asked why she had never pursued so many of her wishes before her transformative summer on Santorini, she laments that there are always consequences. In a lot of ways, she’s my main identification figure in this film. Michael, on the other hand, has the courage to experiment and take risks, but feels that he has been denied the opportunity by the need to meet other people’s expectations of him. Indeed, that’s a large part of his reason for coming to Greece in the first place— he wanted to do something that was not part of the plan. In light of that sentiment, it’s worth looking closely at the fact that he’s living with a girl he’s been dating since high school, whose lengthy prior friendship with him must have made their couplehood seem foreordained. If that isn’t “the plan,” then I don’t know what would be.

Sure enough, Michael and Cathy haven’t been on the island a week when his attention begins to stray, and his frustrations with his safe, comfortable girlfriend begin mounting up. In particular, Michael starts fixating on a beautiful woman a few years older than him (Valerie Quennessen, who can be briefly seen shackled to a megalith in Conan the Barbarian), who lives in the house on the next outcropping downhill from him and Cathy, close enough for him to spy on her through his binoculars, but far enough away that she probably can’t tell that that’s what he’s doing. Michael doesn’t limit his surveillance of his lovely neighbor to the villa’s courtyard. In fact, a modern infatuee who conducted himself like Michael would surely get himself arrested on stalking charges. Nevertheless, the woman down the street seems receptive enough when Michael finally works up the nerve to speak to her. Turns out her name is Lina, but that’s pretty much the only thing she cares to reveal about herself; were it not for her pronounced French accent, Michael wouldn’t even know where she was from. Instead of conversation, the day they spend in each other’s company is given over almost purely to physical interaction of one sort or another, and although it takes some getting used to, Michael eventually decides that he likes that just fine.

As you might imagine, Cathy is very curious about where Michael has been for the last eighteen hours or so when he finally returns at around 3:30 in the morning. Remarkably, Michael is sufficiently upstanding to tell her the truth, and to open up to her about the psychological and emotional underpinnings of his infidelity. Cathy takes it about as well as can be expected. She hisses, “Fine! Get it out of your system!” once he finishes his spiel, and she refuses to have much to do with him for the next day or two while he attempts to do just that, but at least she doesn’t throw him out of the villa, or head back to the States without him. Even so, Cathy finds that she can’t handle her boyfriend’s experimentation nearly as well as she thought she could, and she finds herself standing on Lina’s doorstep one morning, engineering a confrontation. The results would not have been what Cathy had expected, even if she had really known what her expectations were. Lina invites her ostensible rival inside, offers her a cup of tea, and then immediately explains that the two women are in fact not rivals. Lina isn’t looking for a relationship with anybody, let alone with some American boy who already has a girlfriend and will be vanishing back across the Atlantic in less than two months— her whole reason for ditching France for this tiny, out-of-the-way island was to escape from complications and entanglements. On the other hand, Lina does not apologize for screwing around with Michael, nor does she promise not to do it anymore. What she does is offer Cathy a bit of philosophical advice: “Jealousy doesn’t show that you love someone. It only shows how insecure you are.”

Much to Cathy’s astonishment— and to Michael’s even more so— she decides that she actually likes Lina. Not only that, Lina exhibits none of the reticence with Cathy that she had with the boy. It’s Cathy who discovers that Lina is an archeologist, for example, and that she had been in love with an older, married man back home. At first, Michael is a bit put out by the friendship developing between his two girlfriends (after all, he took up with Lina at least partly because he wanted something in his life that didn’t fit in with the routine), but he soon comes to see that it holds advantages for him. Not only does Cathy’s jealousy diminish in direct proportion to the amount of time she spends with Lina, but Lina also becomes more emotionally and intellectually accessible when Cathy is around. After perhaps a week or two of tentative advances, the inevitable happens, and the threesome engage in their first threesome. From that point on, Cathy and Lina accept each other as Michael’s coequal girlfriends, and such a wonderful time is had by all that not even an unexpected visit from Cathy’s domineering mother (Barbara Rush, from Death Car on the Freeway and It Came from Outer Space) and one of her harridan friends (Carole Cook) can harsh the kids’ polyamorous groove. Lina introduces the Americans to her drag-queen friend, Cosmo (Carlos Rodriguez Ramos), and his equally sexually ambiguous husband, leads them on tours of the buried Minoan city she’s helping to excavate, and takes them on a cruise to Mykonos aboard another friend’s floating party-pad of a yacht. There’s a lot of dancing, a lot of beach parties, a lot of skinny dipping, and an immense amount of sex. Somewhere along the line, Lina even goes so far as to relinquish her lease and move in with Michael and Cathy. But then the Americans make the mistake of throwing a little surprise birthday party for Lina. It isn’t that she doesn’t appreciate the sentiment, and it certainly isn’t that she doesn’t have fun. Rather, it dawns on Lina that, despite her expressed intentions to the contrary, she is becoming emotionally attached to Michael, and for that matter to Cathy as well. Horrified at the prospect of the very messy future she’s setting up for herself, Lina pulls the plug— without so much as a break-up note on the kitchen table, I might add— and seeks simplicity in the arms of a mookish stoner (Hans van Torgenen) who apparently lives in a cave on the beach. The Americans become first worried about Lina’s disappearance, then distraught when they realize that they’ve been abandoned. After moping around the villa without her for a couple of days, Michael and Cathy agree that the time has come to pack up and go home, nevermind that they’ve still got three weeks of their scheduled vacation to go. Cosmo’s husband sets Lina straight just in time, though, and she races to the Santorini airport to intercept Cathy and Michael scant minutes before they would have boarded their flight. Just don’t ask writer/director Randal Kleiser what’s going to happen three weeks from now…

It’s difficult to watch a movie in which every third scene takes place on a nude beach and interpret it as anything other than a softcore skin flick, but Kleiser tried very hard to keep Summer Lovers free of that stigma. I’m still lumping it in with the spawn of Emmanuelle, but the curious fact remains that this is easily the least sleazy sex movie I’ve ever seen— especially considering that it focuses on exactly the sort of unconventional (many would say immoral) sexual arrangement that sleaze cinema has been exploiting since at least the 1920’s. As I said at the beginning of the review, in terms of structure, tone, and cliché employment, Summer Lovers is an utterly ordinary romance film; it just happens that it’s about an ongoing ménage-a-trois, and is set in a place where it’s perfectly normal for the three central characters to spend much of the movie lounging around naked outdoors. Even the sex scenes follow the “steamy buildup, then discreet cutaway just as the action starts” model typical of mainstream romance pictures. The latter seems an odd choice at first, given what Kleiser is willing to show outside the bedroom, but I came away with the impression that it was a deliberate tactic in service of the movie’s big subversion. For what makes Summer Lovers really remarkable is that it goes out of its way not to condemn Michael, Cathy, and Lina for their departure from current sexual and romantic norms, even to the extent of cheating in their favor during what few plot developments worthy of the name the movie contains. That, I think, is why it ends the way it does, with all of the issues raised by the final act deferred— because to address them in any slightly honest way would compromise the happily-ever-after, giving the audience some basis for believing that the protagonists were getting what they deserved, and because that is exactly opposite from what Kleiser seems to have had in mind. Thus we don’t get to see the extremely uncomfortable conversation between Cathy and her mom that must surely be in the offing, nor do we get to see what happens when the summer ends, and the time comes for Cathy and Michael to return to the US. And because graphic sex scenes (even softcore ones) would tend to paint the central trio as libertines rather than lovers (at least according to the dysfunctionally prurient puritanism of American pop culture), we don’t get to see any of those, either. The same motive may also underlie Kleiser’s interesting avoidance of what, outside of Summer Lovers, is a nearly universal feature of girl-boy-girl ménage-a-trois stories. Except for one scene in which Lina rubs suntan lotion on Cathy’s back while they sunbathe atop a sea cliff, there isn’t the faintest hint of lesbianism in their relationship; they may both be Michael’s lover, but they aren’t each other’s. In fact, the bi-curious one here is Michael, although Cathy puts the kibosh on that the second it comes up, commanding him, “Don’t pursue it! Life’s complicated enough already!” It’s as though Kleiser figures he’s giving the viewer enough to swallow with just the polyamory, and that throwing in other forms of sexual fluidity, too, would merely muddy the message. Of course, whether you want messages at all in a movie like this is a question of taste that you’ll have to answer for yourself.

As a side-effect of its scrupulous eschewal of the usual soft-porn raunch, Summer Lovers demonstrates just how sexy it’s possible for a movie to be without it. Kleiser essentially takes the philosophy behind the string of 60’s and 70’s court decisions holding that nude is not by itself synonymous with lewd at face value, and makes it Summer Lovers’ operative theory. The camera never leers or ogles the way you’d expect it to, but there is an immense amount of very appealing flesh on display in this film, and of both sexes, at that. For anybody who ever left Splash wishing for more than those few seconds of Daryl Hannah’s bare ass, head on over here, and Kleiser will be happy to set you up. You’ll get very well acquainted with Valerie Quennessen’s and Peter Gallagher’s anatomy, too, to say nothing of about five zillion toned and tanned extras in the numerous beach scenes. All those bodies very quickly merge with the gorgeous and picturesque scenery— the translucent, blue-green water of the Aegean, the intricately craggy and cave-pocked cliffs surrounding the lagoon, the charming clutter of whitewashed cottages crowding each other up the slopes of the ridge— and eventually you realize that you’ve spent the movie’s whole running time simply awash in beauty, be it living or inanimate, natural or man-made. It’s a state that tends to leave one remarkably tolerant of things like plot anemia, dramatic dishonesty, and wobbly acting.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact