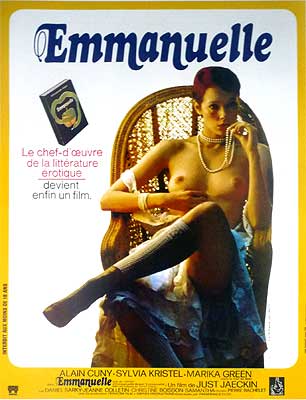

Emmanuelle (1974) ***½

Emmanuelle (1974) ***½

Okay, folks... Let’s show a little respect here. Not only are we talking about the movie that temporarily saved sexploitation as we know it from certain death at the strangling hands of hardcore, but we are arguably talking about the movie that saved the entire French cinema industry from an equally certain death at the strangling hands of television and Hollywood imports! You may not believe this, but Emmanuelle (based on Emmanuelle Arsan’s notorious novel of the same name) isn’t just the most successful skin flick in history— it was also the highest-grossing French movie of the entire 20th century. Not a bad record for what is really just a high-priced exercise in glossy smut.

To understand how one little softcore porno (okay, a big softcore porno) could have such a far-reaching effect, you need to know a couple of things about what was going on in both the French movie industry and in the international sex-film genre in the early 1970’s. France, like most of the civilized world, experienced a wave of social unrest in the late 1960’s, and in marked contrast to the American experience, that unrest actually resulted in a major change in the way the government conducted itself. The new Giscardien government rode to power on a series of promises to liberalize France, and a new and more permissive view on the arts— entailing, among other things, a drastic relaxation of film censorship— was part and parcel of that promised liberalization. Naturally, this led directly to franker depictions of sexuality, especially in the movies, culminating in the appearance of vast quantities of big-budget hardcore pornography by 1975. But before the hardcore boom hit, there was a sexploitation explosion, of which Emmanuelle was the crowning achievement. The tremendous success of this film points to a surprising but inescapable fact about movies in France in the mid-70’s. Theater audiences had been shrinking steadily ever since the advent of TV; then suddenly, when the sex movies began appearing, theater attendance started to rise meteorically. And in the wake of Emmanuelle, even big-name filmmakers, working for big-time studios, started cranking out porn, both hard- and softcore. Indeed, the porn-fueled cinematic renaissance reached such vast proportions as to become acutely embarrassing to the authorities whose policies had made it possible. Sure, they were happy to see their home-grown movie industry prospering, but to have all that prosperity built on a foundation of smut?! In due time, this feeling would lead to a revival of restrictions on adult movies, but for most of the 70’s, conditions were such that one can talk seriously about a Golden Age of French Porn.

Meanwhile, throughout the rest of Europe and in America, where the sexploitation cauldron had already been bubbling for a decade when Emmanuelle arrived on the scene, the rise of hardcore was threatening to kill off the old school of less explicit dirty movies outright. The heart of the matter was that the core audience for the films of directors like Russ Meyer and Doris Wishman— the raincoat crowd— had little interest in movies per se; they just wanted to see naked women. When it became possible for them not just to see naked women, but to see naked women fucking, for real, in front of the camera, with little or no story to get in the way of that central experience, they deserted sexploitation en masse in favor of hardcore. But when Emmanuelle, its sequels, and its legions of imitators appeared, a new audience for softcore opened up. People who had previously been turned off by the perceived squalor and artistic vacuity of the old nudies were drawn to the new European imports by a combination of their high production values, their staggeringly lovely female stars, and the paper-thin pretenses to philosophical significance made by their stories. It turned out there was a mainstream audience for softcore after all, provided that that audience could fool itself into believing it was seeking art rather than titillation. And even after the novelty wore off, and the public’s taste began to re-conservatize in the early 80’s, enough filmmakers had learned the tricks that the genre could survive even the death of low-budget theatrical cinema by moving into the direct-to-video and made-for-cable markets, where it continued to thrive until the internet disrupted the whole business of erotic filmmaking in the back half of the 2000’s. And we more or less owe it all to Emmanuelle.

Now as is usually the case with these movies, the story here frequently disappears behind the clouds of steam given off by all the sex, but if you pay close attention, you’ll see that there definitely is a story unfolding. Emmanuelle (the incomparable Sylvia Kristel, who had previously appeared in such little-known movies as Because of the Cats and Frank & Eva) is the wife of a French diplomat named Jean (Daniel Sarky) who has just been dispatched to the embassy in Bangkok. Jean and Emmanuelle have what could probably be best described as an open marriage— and as you might imagine, it is mostly Jean who takes advantage of that “openness.” For her part, Emmanuelle has little interest in men other than her husband, and for all his frequent cajoling, Jean has had little success in persuading her to sleep around. (Don’t misunderstand the situation, though— even Jean’s encouragement of infidelity on his wife’s part is purely self-serving. The thought of his friends banging Emmanuelle turns him on almost as much as the thought of banging her himself.) But when Emmanuelle flies out to join Jean in Bangkok, she finds herself in an environment of Dionysian sexual adventurism that would make Petronius blush.

Emmanuelle hasn’t been in Bangkok more than a day when the peer pressure for her to step out and go wild begins. All of Jean’s embassy friends have stay-at-home wives who, as Emmanuelle herself will later describe it, “practice idleness as a high art.” Spoiled rotten by their wealth, with nothing to do all day, and with their husbands frequently disappearing for days at a time on diplomatic assignments, it is scarcely surprising that they try to fill the empty hours with sex. And because this is a European porno we’re talking about, they’re not terribly picky about whether they sate their sexual appetites with men or with women. In fact, at their very first meeting, a woman named Ariane (Jeanne Colletin from Shock Treatment) tries to seduce Emmanuelle while she sunbathes nude beside the swimming pool that is one of the embassy wives’ favorite hangouts. Undaunted by her initial lack of success, Ariane will spend the rest of the movie trying to get into Emmanuelle’s pants.

Ariane isn’t the only woman Emmanuelle meets that day at the pool who will come to play an important role in the transformation she will soon undergo, either. This occasion marks her first encounter with a female archaeologist named Bea (Marika Green), whom Emmanuelle spies working on her tan on the far side of the pool, and with a remarkably forward girl named Marie-Ange (Christine Boisson of Born for Hell, who was all of seventeen years old when she appeared in Emmanuelle— pederasts take note!). Marie-Ange takes an instant liking to Emmanuelle, and arranges to come visit her at her husband’s borrowed mansion the very next day.

Marie-Ange is just about the most uninhibited teenage girl you’ll ever see in a movie with a budget this big. After flirting with Jean on her way into the house, she finds Emmanuelle asleep, and takes advantage of the situation to cop a feel. When the older woman wakes up, Marie-Ange immediately starts talking sex. First she compliments Emmanuelle on her appearance in the framed nude photos of her that make up so much of her home’s interior decor. Then she wants to know if Emmanuelle has any more explicit pictures hidden somewhere— what the girl really wants is to see shots of her host having sex. When no home-brew porn is forthcoming, Marie-Ange follows Emmanuelle out onto the mansion’s porch, strips off her top, sits down in one of the hanging wicker chairs that are the veranda’s principal furniture, unzips her shorts, and begins masturbating while Emmanuelle watches, wide-eyed with astonishment. Apparently fingering yourself is contagious, though, because just minutes later, Emmanuelle is at it herself, fantasizing about the one time she did cheat on her husband— with two different strangers in rapid succession on the same 747! The point here is that Marie-Ange is, for all her youth, far more sophisticated sexually than Emmanuelle, and from this moment on, the girl begins acting as Emmanuelle’s coach, as it were, leading her along as she explores the outer limits of her own sexuality.

It is Marie-Ange who introduces Emmanuelle to Mario (Alain Cuny, from the widely maligned and mostly forgotten 1956 version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame), a loutish lothario old enough to be her husband’s father. Marie-Ange seems to think Emmanuelle could benefit from an affair with the old creep, but Emmanuelle isn’t buying it. The only person she wants to have an affair with is Bea. None of the other women want to introduce her, though (no explanation for their refusal is ever even hinted at), so our heroine is forced to take matters into her own hands. She corners Bea at an embassy party, and makes a date with her for the following afternoon. It can’t be any later than 2:00 p.m., and Emmanuelle isn’t going to get another chance any time soon, because Bea is leaving the next evening for an archeological dig out in the Thai countryside. But the two women really hit it off (Bea finds Emmanuelle “exciting,” while Emmanuelle is thrilled to finally meet a woman in Bangkok who actually does something), and when it’s time for Bea to leave, Emmanuelle makes a spur-of-the-moment decision to accompany her on the dig. It is a fateful choice on Emmanuelle’s part, the event on which the entire rest of the movie will hinge.

You see, after a most of a week in Bea’s company, Emmanuelle realizes that she has fallen in love with her. Apart from the obvious difficulties that this presents for a previously happily-married woman, there is also the small problem that Bea herself is only interested in Emmanuelle because she’s good company and a fantastic lay. Emmanuelle is heartbroken when she hears the truth at last. She sneaks away from Bea’s camp that night while the archeologist sleeps, and then hauls the burden of her unrequited love back to Bangkok. Meanwhile, her disappearance has had some unexpected effects. Jean, for all his faux-sophisticated talk of open marriages and sexual emancipation, is devastated by Emmanuelle’s apparent desertion. He has spent the week or so that Emmanuelle was away haunting the bordellos of Bangkok, taking in the sex-shows in bourbon-addled misery, and having bitter, joyless affairs with the other embassy wives— Ariane especially— and apparently with Marie-Ange as well. And when Emmanuelle finally does return, Jean’s response to their reunion is even more surprising— after hearing his wife’s tale of spurned love with the archeologist, he turns her over to Mario for some advanced training in emotion-free sexuality! Then, with Emmanuelle in Mario’s capable hands, Jean flies off on some assignment or other, leaving Bangkok, Emmanuelle, and the movie behind him.

It is at this point that Emmanuelle takes a sharp turn toward the disturbingly perverse. In fact, the movie comes increasingly to resemble Pauline Reage’s The Story of O (it’s probably no coincidence that Emmanuelle director Just Jaekin would adapt that novel to the screen in 1975). You see, Mario has clearly been reading his de Sade. Like just about everyone else in this movie, he regards Emmanuelle’s sentimentality as a personal failing, and he considers it his job to set her straight on the true purpose and potential of sexuality— its value as the ultimate instrument of social revolution. The hippy conception of free love is positively Victorian compared to what Mario is talking about. And yet, as with Jean, it is immediately obvious that Mario’s “philosophy” is merely a cover story. In reality, Mario is nothing but a dirty old man who likes to watch beautiful women debase themselves. And yet, Emmanuelle takes his “lessons” to heart, and goes along with everything he asks of her, no matter how extreme or humiliating. As the closing credits roll, Emmanuelle is still in Mario’s hands, with who knows how much more time remaining before Jean comes home to reclaim her. If, indeed, he means to reclaim her at all.

It isn’t often that one encounters polyphony in an exploitation movie, and for this reason, when it does make an appearance, it is only natural to wonder whether it was put there on purpose, or whether the movie seems to be saying (and meaning) several contradictory things at once because its creators were simply incompetent. And the messages here certainly are mixed. On the surface, Emmanuelle appears to be yet another take on the ever-popular sexual awakening theme. But note that after Emmanuelle is rejected by Bea, the character of her “awakening” changes completely. Until then, Emmanuelle pursues her own emerging sexual identity, for her own reasons. Sure, Ariane, Bea, and especially Marie-Ange help out, but they really only facilitate Emmanuelle’s mostly self-directed experimentation, experimentation which is motivated by a desire to find the ultimate physical, sensual expression of her feelings for Jean, and later for Bea. But when Bea does not return her love, Emmanuelle seems to decide that Jean and Ariane were right after all— that it is hopelessly adolescent to want sex to be about anything more than the interplay of nerve endings, and that it is the very height of naivety to expect it to be anything more. Notice, however, that Jean’s own reaction to Emmanuelle’s affair with Bea demonstrates in the clearest possible terms that even he is emotionally incapable of practicing what he preaches. Seen in this light, Emmanuelle’s behavior looks absolutely tragic, motivated not by a desire to give her feelings their full vent, but by a desperate longing to kill them off so that they can never torment her again. Yet Jaekin seems to be asking us to believe this is a change for the better.

And then there’s Mario. Like the man whose ideas he borrows, Mario is a revolutionary only in his own mind. In reality, he is simply an exploiter of women, and all the more odious because he would seek to dignify his depravity by passing it off as philosophy. His idea of moral instruction in accordance with what he calls “the law of the future” is to invite random strangers to manhandle Emmanuelle on the street, to incite dope fiends to gang-rape her in an opium den, and to give her away as a prize in an impromptu boxing match. He isn’t broadening her horizons, as he would have her (and us) believe. No, Mario’s tutelage merely makes Emmanuelle a pawn in his squalid, ugly games, an instrument of his pleasure. And because Jean willingly hands Emmanuelle over to Mario, he is complicit in his “beloved” wife’s debasement.

So what are we in the audience supposed to make of all this? Is the apparent contradiction between the events of Emmanuelle’s final half-hour and the attitude with which Jaekin’s camera regards them an accident, or did he realize that he was making a very ambiguous film? I think the background music playing during the final scene may have something to tell us on this score. In this scene, Emmanuelle has just returned from her big night out with Mario, and she is getting herself ready for whatever sleazy thing he plans to have her do next. While she applies her makeup, the main musical cue is an upbeat, but slightly wistful piece for acoustic guitar, one that we have heard any number of times previously— it is very similar, if not identical, to the music that accompanied the earlier romantic montage that established Emmanuelle’s fast-moving relationship with Bea. But there is one major difference. Underlying the guitar this time is a second cue, played on an organ or similar instrument, which will be instantly familiar to anyone who has ever seen a horror movie made since about 1965. It’s the “They’re coming to get you” music, and its presence here leads me to believe that somebody (even if it was only the musical director) saw what was really going on in this movie.

Now before I take my leave of Emmanuelle, I think it would be appropriate to say a few words about sequels, ripoffs, and cash-ins. There are literally dozens of movies out there that would have you believe they are somehow connected to this one. The vast majority are not. Emmanuelle spawned two sequels in the 70’s, Emmanuelle: The Joys of a Woman and Goodbye, Emmanuelle, both with Sylvia Kristel in the starring role. Then, in the mid-80’s, the studio revived the series, and Emmanuelle IV, Emmanuelle V, and Emmanuelle VI were made between 1984 and 1989. Only the first of these 80’s sequels featured Kristel, and it only briefly. (I’ll go into detail whenever I get around to reviewing Emmanuelle IV— it’ll happen someday, I promise.) Next, in 1993, another batch of sequels was made for broadcast on French television, apparently in a desperate, last-ditch attempt to resuscitate Kristel’s flagging career. There were a total of seven such films: Emmanuelle Forever (not to be confused with Forever Emmanuelle), Emmanuelle’s Revenge, Emmanuelle in Venice, Emmanuelle’s Love, Emmanuelle’s Magic, Emmanuelle’s Perfume, and Emmanuelle’s Secret. Finally, also in 1993, a new, seventh Emmanuelle film was released to French theaters in order to exploit whatever success had greeted the made-for-TV cycle. Any other movie you see with “Emmanuelle” or “Emanuelle” in the title is a snowjob of one sort or another. Most of these films are of Italian origin, and are sequels to Black Emanuelle, which was made in 1975 and starred Laura Gemser (who had had a brief cameo in the first legitimate Emmanuelle sequel) as the one-“m”ed Emanuelle. (The change of spelling was made for legal reasons— apparently in Europe it isn’t copyright infringement if you spell it differently.) Many others are non-“Emanuelle” Laura Gemser flicks whose U.S. distributors figured (usually rightly) that they would be far more profitable if billed as entries in the “Emmanuelle/Emanuelle” series than if presented as standalone films. A number of totally unrelated European softcore movies also got this treatment, including Laure (aka Forever Emmanuelle), Nea (aka A Young Emmanuelle), and Il Mondo dei Sensi di Emy Wong (aka Yellow Emanuelle). Thus it is that there are women’s prison movies, gun-toting action flicks, and even a couple of plantation-porn films set in the antebellum American South whose English-language versions are called “Emanuelle [Does Something].” Meanwhile, on this side of the Atlantic, another string of fraudulent sequels (this one with a sci-fi bent) was made for the cable TV market, starring former “Baywatch” babe Krista Allen. And even then the Emmanuelle story wasn’t quite over. Yet another series of phony sequels got underway at the turn of the century; its several direct-to-video entries variously bore the before-the-colon monikers Emmanuelle 2000 or Emmanuellle 2001. There may be something to those titles that put “Emmanuelle” and “forever” side-by-side after all...

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact