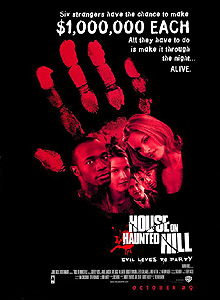

House on Haunted Hill (1999) **˝

House on Haunted Hill (1999) **˝

Like Louis S. Arkoff’s Creature Features label, Dark Castle Entertainment is one of the more peculiar production houses to emerge from the American cinema industry in recent years. Though the company has diverged from this a bit since its inception, Dark Castle was originally formed expressly for the purpose of remaking the works of producer/director William Castle. This would seem to be about as quixotic a cinematic mission as you could ask for. Apart from a handful of freaks and weirdoes (myself numbered proudly among them), nobody much remembers Castle today, and because his fans are close to unanimous on the point that what makes his movies so entertaining is the perspective and personality that Castle himself brought to them, a series of remakes isn’t likely to appeal to us much. It’s a situation in which you kind of have to ask, “Just whom do you think you’re making these movies for, anyway?” and considering that the company has produced only two Castle remakes so far, it may well be that Dark Castle bosses Robert Zemeckis and Joel Silver have come around to seeing things that way themselves. In any case, having embarked upon the task of remaking Castle, The House on Haunted Hill would probably seem like the most logical place to start. It was one of the director’s more successful films, and it is one of the two that have faded the least from popular memory in the intervening decades. On the other hand, because it was one of Castle’s very best movies, it also stood to gain the least from the remaking, and with Vincent Price both an extremely tough act to follow and six years in his grave by 1999, the chances of the new version failing to live up to the old by a sizable margin were even greater than usual. And though it gets off to a strong start, with a well-chosen cast, a crafty reworking of the original premise, and unexpectedly astute direction from William Malone (the high point of whose feature film career is the much-disdained Creature), failing by a sizable margin to equal the Castle version is precisely what this House on Haunted Hill does.

The Dark Castle House on Haunted Hill begins by addressing a point which the original never dealt with— it offers a compelling explanation for the titular house’s forbiddingly institutional appearance. (Of course, in light of the real explanation— that Charles Ennis pretty much just wanted to live in the world’s ugliest mansion, while Frank Lloyd Wright was more than happy to see to it that he would— it’s easy enough to see why a fellow Californian like Castle wouldn’t reckon the house far enough out of the ordinary to require an origin story.) The current House on Haunted Hill looks institutional because it was built to be an institution. Up until one disastrous night in 1931, the sinister building (which in this version looks rather like what might have happened had Ennis commissioned Wright to build him his own private Minas Tirith) was the mental hospital run by Dr. Richard Vannacutt (Jeffrey Combs, from The Pit and the Pendulum and Castle Freak). Vannacutt was as far out of his mind as any of his patients, and he devoted his energies not to curing their insanity, but to performing hideous and apparently pointless medical experiments upon them. Eventually, the crazies broke loose and went on a killing spree, murdering every staff member they could get their hands on in as close an approximation of Vannacutt’s own style as their lack of organized surgical training would permit. They also set the place on fire, and though the hospital’s fortress-like construction preserved the structural integrity of the building itself, it also prevented anyone— either inmate or employee— from escaping the conflagration. Years later, the hospital was bought by an eccentric multi-zillionaire who restored the place and converted it into a private residence; he and his son are both reputed to have died within its walls under most unusual circumstances. Finally, in the present day, Evelyn Stockard-Price (Famke Janssen, from Lord of Illusions and The Faculty), the wife of another unfathomably wealthy man, sees a television segment on “the House on Haunted Hill,” and realizes she’s found the perfect place to hold her upcoming birthday party.

Meanwhile, Evelyn’s husband, Stephen H. Price (Geoffrey Rush)— whose last name is surely not an accident— is taking a TV news reporter (Lisa Loeb) and her photographer (James Marsters, of “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” fame, who gets opening credits billing despite having but two lines and a single scene in the film— Castle would have approved heartily) on a tour of the newly opened latest addition to his nationwide amusement park empire. The main point of this scene is to give some indication of Price’s devilish imagination and immense flair for showmanship, both qualities which will be distinctly relevant to coming events. After cutting the journalists loose, Stephen receives a telephone call from Evelyn informing him of her decision regarding the party, and telling him where to find the guest list; Stephen sticks the list right in the shredder, however, and substitutes one of his own. Stranger still is what happens the moment the roller coaster tycoon leaves his office— somebody hacks into his computer, deletes his version of the guest list, and substitutes yet a third.

The doubly revised list consists of but four names: Eddie Baker (Equilibrium’s Taye Diggs), Donald Blackburn (Peter Gallagher), Melissa Marr (Bridgette Wilson, from I Know What You Did Last Summer and Final Vendetta), and Jennifer Jenzen (Ali Larter, of Final Destination and Final Destination 2). Blackburn is a doctor, Baker is a former professional baseball player, Marr was up until recently the hostess of some TV game show or other, and Jenzen is a movie studio executive— or so she says anyway. In actual fact, her name is Sara Wolfe, and she’s Jenzen’s disgruntled personal assistant, impersonating her hated boss for reasons which will become clear in just a moment. Both Stephen and Evelyn claim never to have heard of any of these people, and it causes much suspicion and acrimony when this gang of strangers arrives at the house knowing only that some rich guy they don’t even know has called them out to a horror-themed birthday party, promising to pay a million dollars to anyone who survives the night. As with the original film, it’s never quite clear just what game Stephen Price is really playing, but Evelyn is quite certain the ultimate object is her demise— which would be only fair if it were true, because it’s perfectly plain that Evelyn would like nothing better than for Stephen to die so that she could get down to the serious business of spending his money. And what’s plainer still is that Watson Pritchett (Chris Kattan, of Santa’s Slay), the current owner of the house and the grandson of the man who bought it when it was still nothing but the burned-out hulk of a lunatic asylum, wants nothing to do with any of this now that he has conveyed everybody to the front door; he just wants to collect his fee from Price and go home. Pritchett, you see, believes the house is haunted not only by the wrathful spirits of Vannacutt, his victims, and his accomplices, but by something even worse which he refers to as “the Darkness.” So it sure does sound like fun times are ahead when the same assemblage of impenetrable steel shutters that doomed the inmates back in ‘31 unexpectedly locks down, trapping Pritchett, the Prices, and their guests inside, doesn’t it?

The 1999 House on Haunted Hill, as has been remarked upon already by practically everybody, is a damn good film with a fucking atrocious ending. Right up until the third act, it represents a deft attempt to reassemble the elements of Castle’s version into something which is simultaneously new and familiar. Each character has an obvious analogue in the 1958 film, but in no case except possibly that of Watson Pritchett (the only one, incidentally, to retain approximately his original name) can the paired characters be thought of as interchangeable. This version retains its predecessor’s focus on the constant sparring between the millionaire and his wife, in a way that preserves both the gleefully arch tone that was so important back in the 50’s and the vital functionality of keeping the audience off-balance regarding which character is about to draw down on which. At the same time, it also toys with our expectations, making the relationship between the Prices rather more complicated than it appears at first glance. Chris Kattan surprises by actually being funny (a term of service in the trenches of “Saturday Night Live” isn’t exactly an auspicious entry for a comic actor to have on his resume, after all) in the part of the one person who knows enough from the get-go to be scared out of his wits by the prospect of spending any meaningful amount of time in the house. And most satisfyingly of all, the remake manages to include updated versions of all the original’s major set-pieces while putting the majority of them to new and unexpected uses.

That’s the good news. The bad news follows more or less inevitably from House on Haunted Hill’s date of release. Naturally, 1999 was way too late in the game to make a movie with a title like that and not deliver on some authentic, no-bullshit ghosts, so it should come as little surprise that this movie quite rapidly quits dicking around to present us with an unambiguous display of supernatural malevolence. The first time around, William Malone and screenwriter Dick Beebe do it absolutely right, showing us something eerie and then implying something else that’s extraordinarily gruesome a moment later. And if they had been content with something as “mundane” as a huge, old building haunted by thousands of ghosts who are not only aggrieved and deadly, but batshit insane on top of it all, they probably could have kept on ratcheting up the explicitness of the scare scenes while maintaining the effectiveness of that first one. But no. Instead, they had to bring in “the Darkness.” With a vague-ass name like that in a movie from the late 1990’s, you just know there’s only one possible thing for the Darkness to be once it finally deigns to put in an appearance. You got it— it’s a big, tacky CGI effect. From the moment the Darkness shows up, House on Haunted Hill takes on a most unfortunate resemblance to that other digitally-fixated haunted-house movie from 1999, Jan De Bont’s The Haunting. It’s all downhill from there— and fast, too. Before all is said and done, House on Haunted Hill will even come perilously close to “When in doubt, just blow shit up,” as the one non-computer-generated manifestation of the Darkness takes the form of a cascade of exploding flooring, much like that seen during the climax of John Carpenter’s The Thing. Somehow it seemed to make more sense when a shape-shifting alien was doing it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact