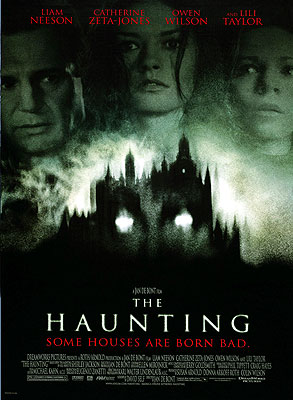

The Haunting (1999) ½

The Haunting (1999) ½

Okay, boys and girls, the word of the day is “bullshit.” There will be many opportunities for you to employ the word of the day before I am through discussing the ill-advised 1999 remake of The Haunting; indeed I find myself wondering if perhaps that wasn’t the very effect that the people responsible for this travesty were aiming for. Not that I’m surprised or anything, mind you. What do you expect when you turn Jan De Bont— the director of Speed— loose on a remake of a film renowned the world over as a paragon of class and restraint?

It seems like it might be kind of okay at first, what with the long panning shot over the roof of the palatial Hill House just after dawn that precedes the credits, but do not be deceived. The filmmakers display their marked preference for the depressingly obvious just moments later, when they present us with the spectacle of Eleanor Vance (The Addiction’s Lili Taylor) fighting with her sister and brother-in-law over the terms of her mother’s will. That will names the brother-in-law executor of the estate, despite the fact that it was Eleanor who did all the hard, grimy work of caring for her mother for the last eleven years of her life, during which the old lady was bed-ridden and senile, and in a foul mood more or less 24 hours a day. This fight is scripted in such a way as to leave no doubt that the sister and her husband are utter heels, and are not just complying with the admittedly unfair terms of the will— hell, even their obnoxious son plays a role in painting the situation in the starkest possible black and white. The upshot of the deal is that big sister is selling Mom’s old apartment out from under the unemployed Eleanor, and all Eleanor gets out of it is the dead woman’s car— a 1975 AMC Gremlin! (While we’re on the subject of that Gremlin, I’d like to draw your attention to the fact that someone seems to have run off with its characteristic Gremlin-logo screw-on gas cap. This little detail is just about the only authentic, believable touch in the whole film.) Big sister’s mock generosity with the ancient car is the last straw, and Eleanor throws her, her husband, and her pig-faced brat out of the apartment.

That’s when she receives a telephone call from the office of a Dr. David Marrow (Liam Neeson, from Darkman and Krull... okay, okay— and Star Wars, Episode I: The Phantom Menace, too), asking her to take part in an experimental study of insomnia, something Eleanor has suffered from for years. The study pays $900 per week, and will take place in a huge old mansion in New England, a good nine miles from the nearest human being. All in all, it sounds like just the thing to take Eleanor’s mind off her troubles, and who knows— maybe Dr. Marrow will even find a way to make Eleanor sleep. She signs up for the study immediately.

But all is not as it seems. Marrow, you see, is not studying insomnia at all, but fear. He and his assistants, Mary Lambretta (Alix Koromzay of Mimic and The Girl with the Hungry Eyes) and Todd Hacket (Todd Field), have chosen Hill House as the site for their experiments because it is supposed to be haunted, and its quirky, eccentric architecture and interior design make the stories easy to believe. All three experimental subjects— Eleanor, Theo (Catherine Zeta-Jones), and Luke Sanderson (Owen Wilson, in whose career The Haunting was the logical next step after Anaconda and Armageddon)— are all highly suggestible and emotionally disturbed in addition to having a hard time getting to sleep at night. Marrow figures it’ll be easy to sell them on the supposed haunting, after which all he’ll have to do is sit back and take careful notes on the action. Asshole.

Eleanor is the first one to arrive at Hill House. She gets a stern and vaguely threatening greeting from Mr. and Mrs. Dudley, the caretakers (Bruce Dern, of World Gone Wild and Hush... Hush, Sweet Charlotte, and Marian Seldes), and is then shown to her room. Shortly thereafter, Theo arrives, gets the same speech from Mrs. Dudley that Eleanor did, and is set up in the room next door to Eleanor’s. Theo and Eleanor introduce themselves to each other (some of the most unconvincing personal expository dialogue I’ve ever encountered, here) and then begin exploring Hill House. As regards the interiors of the place, allow me to remind you of the word of the day. This is not a house. Nobody, no matter how rich and unbalanced, would ever build a house that looked like this— baby-head carvings all over every square inch of everything, dangerous pointy things sticking out at all angles from all over the place, arrangements of mirrors designed specifically to make you lose your bearings, huge bronze statues distributed randomly to block rooms and hallways, a giant metal door with cast bas-relief figures inspired by Rodin’s The Gate of Hell. No, what this is is a movie set, no two ways about it, and fuck Jan De Bont right in the ass for thinking his audience too stupid to tell the difference. Anyway, before long, the other characters all show up, and Dr. Marrow begins slinging them his bullshit about his supposed insomnia research.

It’s while Marrow is delivering his spiel that the first real indication of trouble (unless you count all those sharp things everywhere) surfaces. As the doctor begins his digression on the history of the house (actually the real point of his talk with the three lab rats), one of the tuning pegs in the clavichord beside which Mary Lambretta is standing begins to tighten all by itself. Eventually, the tension on the string attached to that peg becomes so great that the string snaps, whipping up out of the instrument and slashing Mary’s face from cheek to forehead, nearly putting out her right eye. It causes quite a stir, but since nobody saw the tuning peg turning by itself, nobody has any reason to think the grisly occurrence anything but a freak accident. Marrow sends Todd and Mary back to town to have her eye seen to, and then we rejoin our regularly scheduled bullshit, already in progress.

Over the course of that bullshit, it is gradually revealed that Hill House is indeed haunted, and that Marrow isn’t just playing tricks on his test subjects. Specifically, Hill House is haunted by the vengeful spirit of its builder, Hugh Crane, a 19th-century textile baron who intended the mansion as a dream-home for himself, his young wife, and the extensive family he expected to have. Crane’s wife killed herself before she gave her husband any children, however, and it seems that old Hugh began to look at the child laborers in his textile mills as a sort of surrogate family. Indeed, there is some indication that he even began bringing the kids home to live with him at Hill House. Of course, he was also working them to death at the same time, and the ghosts of “Crane’s” children haunt Hill House along with that of their employer. We learn this when Eleanor wakes up from one of the few fitful sleeps she’s thus far had in Hill House to find one of those juvenile ghosts sharing the bed with her. Faced with such a situation, you or I would probably have a total shit attack (in the eloquent words of the script to some 80’s movie whose name I no longer remember), but not Eleanor. No, she strikes up a pleasant little conversation, just as though she were in the company of Casper the Motherfucking Friendly Ghost! This implausible turn of events is made even more galling by the fact that it comes after this movie’s version of the famous door-knocking scene from the original. In other words, Eleanor has already seen reason to believe Hill House is haunted, and that whatever is haunting it means her harm! And yet she’s quite solicitous toward the specter in her bed, and before the movie is over, she will have made friends with an entire grammar school’s worth of ghost children.

It is they who give Eleanor the clues she needs to piece together the truth about Hill House, and about Hugh Crane. They show her where to find the ledger in which Crane recorded the names and vital information of all his employees— the same ledger in which Crane noted the deaths of the children as they occurred. (And by the way, if Crane’s sweatshops were so lethal to work in, why the hell is it that not even a single one of his adult employees seems to have died there? Yet another thing, I suspect, that we can chalk up to the filmmakers’ insistence on making everything in the movie as obvious as possible...) They show her where Crane hid their bodies (why?!?!) after he worked them to death. And most importantly, they lead her to the discovery that Crane had a second wife, a woman named Carolyn, who turns out to have been Eleanor’s great grandmother! Well that certainly explains why the message “Welcome home Eleanor” turned up scrawled across one of the walls in the main parlor, now doesn’t it? (Another brief digression on compulsive obviousness: In Shirley Jackson’s novel, and in the 1963 movie based on it, that message was worded a bit more ambiguously— “Help Eleanor come home.” There are at least three different ways you could read that, and it would seem that was about two ways too many for the makers of this here film.) This is the point at which I completely gave up on The Haunting. Not that I stopped watching it, mind you. I just stopped expecting anything other than complete shit.

And for precisely that reason, this is also the point at which The Haunting stopped disappointing me. To those who are expecting complete shit, the final twenty minutes of this movie deliver in spades. The ghost of Hugh Crane begins taking an active interest in Eleanor starting now, you see, for he is hell bent on hanging on to the imprisoned spirits of the children, while Eleanor is equally hell bent on freeing them from his grasp. The result is an absurd orgy of CGI overkill, culminating in the longest, loudest, stupidest talking-the-monster-to-death scene since Eric Cartman destroyed Saddam Hussein at the end of South Park: Bigger, Longer, Uncut. Absolutely everything to which De Bont’s camera has paid an inordinate amount of attention up to now comes into play here, from the indefensibly pointy wall sconces above Eleanor’s bed to the big bronze door depicting scenes from Purgatory. No cliché is left unemployed, no stone left unturned in the filmmakers’ scramble to dredge up every hoary, overused chestnut in the long history of the cinema of supernatural horror. And every single last one of them is used to cudgel the viewer into insensate submission to The Haunting’s noisy, vapid, empty climax.

I don’t think there’s been a reviewer yet who didn’t express umbrage at seeing so dignified a movie as The Haunting remade as an $80 zillion CGI extravaganza, so I won’t dwell on that subject for too long. But I do at least have to raise the issue. I also need to draw attention to the uniformly miserable performances of the movie’s actors. In light of Dr. Marrow’s cover-story about insomnia research, it’s awfully amusing to see Liam Neeson portraying him as though he were acting in his sleep. Catherine Zeta-Jones contributes nothing to the movie beyond the brevity of her skirts and the depth of her cleavage. I’m tempted to say that Owen Wilson seems to be patterning his performance after Russ Tamblyn’s in the original movie, but somehow I have a hard time believing he’s seen it— it’s probably safer to say that he’s just a doofus of the same species as Tamblyn in his pre-coke years. Finally, though Lili Taylor does often seem to be striving mightily to do something— anything— of value with her leading role, she just doesn’t have it in her to overcome the dog turd of a script that she has to work with here.

Which brings me, at last, to the thing that ruins this movie even more thoroughly than the lifeless acting or De Bont’s tone-deaf, ham-fisted, meat-headed direction. The real insult here is that, despite what the credits say, The Haunting has nothing whatsoever to do with Shirley Jackson’s famous novel. Rather, it plays more like an idiot version of Richard Matheson’s Hell House, tarted up with various gewgaws stolen from Stephen King’s The Shining and braided together with the screenplay from Poltergeist 2: The Other Side. From Hell House, we have the character of Hugh Crane, who is all but indistinguishable from that fine book’s spectral villain, Emeric Belasco. Crane’s hobby of collecting the souls of children echoes the similar avocation of Poltergeist 2’s Reverend Cain. Various effects sequences recall scenes from the print version of The Shining— the one in which Crane’s statuary comes to life to menace Eleanor seems especially similar to The Shining’s topiary lion attack, a scene wisely dropped from the script of Kubrick’s film version. With the underlying armature of the screenplay thus in place, the most famous set-pieces from the 1963 The Haunting— the thing banging on Theo’s door, the face in the wall, the collapse of the spiral staircase— were then grafted thoughtlessly onto the resulting mess wherever they would fit. The final product is not unlike the hash the aliens in the first “Star Trek” pilot made of reassembling Susan Oliver when they pulled her ruined body from her crashed spacecraft— it’s as if writer David Self meant well, but had no idea where the parts belonged, or what they were supposed to do.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact