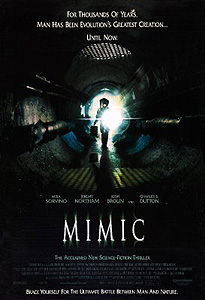

Mimic (1997) ***

Mimic (1997) ***

A few years ago, I was digging through a used book store’s shelves when I found an anthology consisting mostly of public-domain antiquities and Weird Tales leftovers, entitled 100 Creepy Little Creature Stories. It turned out to be a treasure trove of neat shudder-pulp fiction that I’d never even heard of, but by far the most unexpected thing it contained was a tale called “Mimic,” written by Donald A. Wollheim. I hadn’t paid too much attention to the credits when I saw Mimic, the first English-language movie from Mexican dark fantasist Guillermo del Toro, in the theater, and the fact that it was based on a 55-year-old short story completely escaped my notice. So when I read, five paragraphs into the Wollheim piece, “I have always known of the man in the black cloak,” the little archivist who lives somewhere in my brain suddenly sat up and went, “Wait— really? ‘Mimic’ as in Mimic?!” Indeed. The story, as is so often the case with short-form horror fiction, is little more than an extended setup for a “Gotcha!” conclusion, but the central premise of an insect that has not only grown to prodigious size, but evolved to mimic the appearance of a bundled-up man as well, is present in a form not far removed from that it takes on film. I had not been much impressed with the movie initially, but reading the source story got me interested in giving it another try. Now that I have, I find that I’d been rather too hard on it the first time around. It’s hardly a great film, and it shows few hints of the consummate visual stylist that its director would evolve into in the decade to come, but especially in the context of 1997 (which I’ve cited before as an uncommonly bad year for horror movies), Mimic is an extremely serviceable diversion.

Manhattan has a problem. It’s called Strickler’s Disease, and it’s exterminating the island’s children at an appalling rate. There is no cure, no vaccine, and no prospect of either on the horizon. Thus far, the epidemic has yet to reach the mainland, but the results if it did would be catastrophic, and since the primary vector appears to be the ubiquitous American cockroach, the chances of Strickler’s spreading seem excellent. With that in mind, the Centers for Disease Control engage entomologist Dr. Susan Tyler (The Final Cut’s Mira Sorvino) to combat the disease via the one vulnerability it seems to have. Even that is the longest of long shots, though, for if there’s one thing all urbanites know, it’s that ridding a city of its roaches is a labor fit for Herakles. What Tyler eventually settles upon is to genetically engineer a new strain of cockroach with what amounts to a built-in self-destruct device, together with a disease of her own to pass along to the Strickler’s-carrying roach population. Termite DNA renders the Judas Breed (as Tyler dubs her infectious pets) congenitally infertile, while mantis DNA presumably induces the females to slaughter any males that mate with them. The disease, for its part, enzymatically sabotages the metabolism of the normal roaches, so that they quickly starve to death no matter how much they eat. The Judas Breed works like a charm, and within about four months, Strickler’s Disease has gone the way of smallpox. Four months is also supposed to be the maximum lifespan of a Judas roach, so no one need worry about any further destabilization of Manhattan’s vermin ecosystem.

Yeah. Sure. And while you’re not worrying about that, you can also not worry about nuclear waste left to rot in the sewers turning the homeless into man-eating monsters— the two potential concerns have a remarkable amount in common, as we shall see. Three years after the Strickler’s crisis is declared over, people start disappearing from Manhattan. They’re bums and transients for the most part, so nobody much notices except for Chuy (Alexander Goodwin), the autistic ward of an immigrant bootblack named Manny (Giancarlo Giannini, from Black Belly of the Tarantula and Hannibal) who generally plies his trade in one of the city’s many subway stations. Chuy is up late one night, staring out his bedroom window in his habitual vacantly attentive manner, when he sees an elderly man trapped and killed by a tall, overcoat-clad figure in the alley between Manny’s apartment and a raggedy little church that caters to a straight-off-the-boat Asian congregation. The boy’s malformed mind doesn’t really absorb the significance of what he sees, registering only that the killer is wearing “funny shoes.” In fact, if anyone would think to ask Chuy, they’d learn that he’s been seeing lots of funny shoes on the streets at night lately.

There’s more going wrong in that church than raincoaters killing people and dragging their bodies down into its basement, too. The pastor there has apparently been using it as an unlicensed homeless shelter, and the vagrants he has squeezed into it are all sick as dogs with yellow fever. The cops bust the place, and CDC epidemiologist Peter Mann (The Invasion’s Jeremy Northam)— who was Susan Tyler’s agency liaison during the Strickler’s outbreak, and is now her husband— places both the building and everyone who’d been living there under quarantine. Mann doesn’t think much of this at the time, but his sweep of the church once the situation is under control turns up one exceedingly weird detail. Don’t ask him or any of the accompanying cops how, but somebody in there had been in the habit of crapping on the ceiling.

Meanwhile, Tyler has been encouraging the scientific curiosity of the kids in her neighborhood by paying them for unusual insect specimens. Two boys show up one day with the biggest, weirdest bug she’s ever seen— well worth the ten dollars she pays to get her hands on it— and better yet, it’s still alive. The insect looks more or less like a cockroach, but it’s nearly the size of a horseshoe crab. It bites like a motherfucker, too, and Tyler has sustained a fair bit of damage to her fingers by the time she gets the specimen pinned down in a dissecting pan. Two remarkable facts come to light during the many hours she spends poking and prodding at the mysterious bug: (1) it’s nowhere near adulthood despite its mammoth size, and (2) its tissues contain proteins that Tyler has seen nowhere else in the class Insecta but the Judas Breed. Susan rushes immediately to the phone to get in touch with both Mann and her mentor, Dr. Gates (F. Murray Abraham, from Thirteen Ghosts and Star Trek: Insurrection), and while she’s thereby occupied, two tall, slender prowlers in black overcoats break into her lab and steal her specimen.

Naturally, Susan is greatly concerned over the prospect that the Judas Breed not only found a way around the sterility she tried to engineer into it, but has now developed into the huge and aggressive insect she temporarily had in her lab last night. The boys who sold her the bug volunteer the information that they found it in an officially off-limits section of a subway station, and when asked if they saw any egg cases (Tyler helpfully produces a visual aid from one of her books), the kids also take it upon themselves to go looking for some. Neither one of them ever returns from that errand. At the same time, Susan, Peter, and a colleague of Peter’s by the name of Josh (Josh Brolin, of Grindhouse and Hollow Man) go looking around the subway station on their own, but they get chased off before they can find anything useful by a Transit Authority cop called Leonard (Charles S. Dutton, of Cat’s Eye and Alien3), who seems determined to play King Shit of Turd Mountain. Which is lucky for them, actually, but they won’t be finding that out for a while yet. Then Tyler’s friend, Remy (Alix Koromzay, from The Haunting and Ghost in the Machine), calls her out to the water treatment plant where her boyfriend (Norman Reedus, of Blade II and Messengers 2: The Scarecrow) works so that she can have a look at the weird-ass thing he fished out of the tanks this morning. Sewage Man guesses it’s a massive lobster, but it’s really another of the Judas Breed mutations— and it isn’t mature, either, even though the freaking thing is easily as big as Chuy. And because it isn’t deformed in any recognizable way, Tyler concludes that it can’t be just some unique freak of nature. No, the thing from the sewage plant must be a perfectly normal example of its species. Tyler sends Remy over to Dr. Gates’s office with her boyfriend’s find, while she goes to meet up with Peter and Josh, who are at that point shanghaiing Leonard into giving them a guided tour of his subway station. Chuy gets abducted by “Mr. Funny Shoes,” Manny goes to look for him, and thus it is that damn near the entire cast ends up down below ground, facing off against a whole colony of man-sized, man-eating, bipedal roaches that look sufficiently like human beings to sneak into striking range unsuspected.

I think a lot of the reason why I couldn’t appreciate Mimic the first time I saw it was that I simply could not buy into the basic premise. I can accept giant bugs easily enough, and I’ll similarly accept non-human organisms evolving to mimic human appearance for stealth’s sake, but giant bugs evolving a humanoid appearance really is a lot to swallow. What got me past that obstacle this time was a detail that I didn’t pick up on back in 1997, when I was paying at least as much attention to my girlfriend’s thigh as I was to the movie: the Judas Breed’s mimicry is really pretty bad. Their elytra have thickened and enlarged enough to enfold their entire bodies like a leather overcoat, and the plating on their foremost tibiae matches the contours of a human face when the two limbs are held together in front of the insects’ real heads. Only in extremely subdued light would the disguise work, but only in extremely subdued light do we ever see the creatures operate outside their lair. Now, that doesn’t address the vital points that mimicry can evolve only in the presence of selection pressures that favor it (meaning in the present context that those Judas bugs that don’t look enough like people get killed before they have a chance to breed), and that it would therefore be impossible for the insects to reach even this limited degree of copycat fidelity until many generations after their presence was known to us. It’s also a little weird to see a lapse that fundamental coexisting alongside a scene drawing attention to the fact that the Judas Breed have evolved lungs to go with their trenchcoat forewings and false faces— you’d think a writer so clueless about how evolution works wouldn’t sweat a little thing like the main limiting factor on insects’ size being the inefficiency of their respiratory and circulatory systems! Still, recognizing the Judas Breed for the very imperfect mimics they are has eased the load on my disbelief suspenders to the point that I can now close my ears to the harrumphing of Dr. Science and enjoy the movie on its other merits.

Foremost among those other merits is a monster yarn in the classic style, efficiently told despite a rather loose-jointed and ungainly story structure. On the one hand, we have Chuy, who has been keeping tabs on the creatures in his peculiar way, together with Manny, who tries to protect him once the bugs decide that they don’t like being watched. On the other, we have the scientists, who aren’t even aware of the disappearing bums, and whose involvement stems from an altogether different set of concerns. It’s almost as if two originally separate treatments were hastily spliced together, and that ought to ruin the film’s pacing and momentum completely. That it doesn’t testifies to del Toro’s skill at keeping the two plots constantly in motion at comparable rates. Once again, I detect in Mimic an echo of C.H.U.D., which also maintained a quick and steady pace despite juggling several groups of tangentially connected characters. Another thing that del Toro and his co-writer, Matthew Robbins (writer/director of Dragonslayer), do right is to establish that they’re not screwing around early on, when they feed the two juvenile bug-collectors to the monsters. It would appear that everybody is fair game after that, which is a useful impression to create in a movie where the final act depends so heavily upon the good guys doing suicidally risky things in the name of containing a threat that is worth far more than their lives. And last but not least, the monsters themselves are quite good. The Super-Judases were realized via a shrewd combination of computer graphics and practical effects, as often happened in the late 90’s, when CGI wasn’t yet necessarily always the cheapest way to do things. It’s a case of technological limitations coincidentally pushing filmmakers in the direction of best practices, and Mimic joins the ranks of movies from the early days of the digital effects revolution that have held up better over time than comparably budgeted productions from five or even ten years later.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact