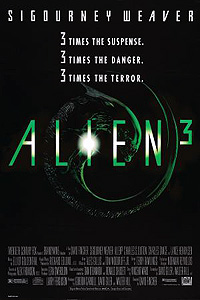

Alien3 (1992) **½

Alien3 (1992) **½

The trouble with sustained greatness is that it creates an obligation either to sustain it further, or to quit while you’re ahead. Create a mediocre sequel to a good movie, and no one’s going to be more than a little disappointed. Make a mediocre sequel to a great movie, on the other hand— especially after somebody already gave it one sequel that was equally great in its own right— and people are going to get pissed off. That, in a leathery, lobe-lidded, space-monster eggshell, is also the problem with Alien3. If it had been a mere rip-off of Alien or Aliens, my feelings toward it (and, or so I suspect, the feelings of fandom in general) would not be nearly as negative. In fact, there are a few filmmakers (Luigi Cozzi springs immediately to mind for some reason) from whom I’d have found Alien3 pretty fucking impressive. Unfortunately, however, this isn’t Alien Contamination 2, nor Creature 2, nor Forbidden World 2, either. It’s goddamned Alien3, and after the two previous movies, a moderately decent retread of the same old material, even when enlivened by some pretty neat production design and a few commendable performances, is nowhere near good enough.

Several other writers have commented on the marked structural similarity between Alien and a 1980’s slasher movie. Alien3 deepens the parallel by utilizing what must surely be the most widely despised opening gambit current among slasher sequels— it kills off the survivors of the last movie before the credits have even wrapped! I don’t mean Ripley, of course (although a couple of Alien3’s astoundingly numerous screenplays and treatments were written with little or no role for the character, for fear that the going rate for Sigourney Weaver’s scruples would be higher than the five and a half million dollars the producers ultimately agreed to pay her), but those who were looking forward to the meaningful return of Hicks, Bishop, and Newt will be getting a big middle finger from the studio instead. You remember how, when Bishop airlifted Ripley, Hicks, and Newt to safety right before the nuclear reactor powering the atmosphere processing plant on LV-426 melted down, he accidentally rescued the queen alien, too? Well, either the queen wasn’t the only representative of her species to hitch a ride in the retraction well for the dropship’s landing gear, or Walter Hill and David Giler (the last of the battalion of screenwriters to contribute to Alien3’s script) didn’t have much of a handle on the creatures’ biology, because a face-hugger has somehow found its way onto the Sulaco, and it causes a cascade of deadly havoc aboard the ship when it tries to melt its way into the hypersleep units to get at the people within. We don’t get to see that havoc clearly, completely, or sequentially (because that would spoil a major third-act plot development), but the upshot is that a fire breaks out, the onboard computer jettisons the emergency escape vehicle containing the afflicted freezer units, and only Ripley remains alive by the time the EEV makes landfall on Fury 161 (or Fioria 161, depending on whether you prefer to follow the dialogue or the onscreen captions).

The good news is, there’s a human settlement on Fury 161; the bad news is, it’s a penal colony. (Specifically, it’s described as a “double Y-chromosome” penal colony, with a capacity of 5000 prisoners. So does that mean the gene-pool of the future is so rife with meiotic fuck-ups that one can populate an entire offworld prison with guys who suffer from supermale syndrome, or did the writers just fail the genetics unit of seventh-grade science class?) The Weyland-Yutani company administers it, of course, but they don’t seem to be terribly interested in it anymore, as there aren’t but a few dozen prisoners these days, and the entirety of the staff consists of Prison Superintendent Andrews (Brian Glover, from Jabberwocky and The Company of Wolves), an administrator called Aaron (Ralph Brown, of The Time Machine and Star Wars, Episode I: The Phantom Menace), and medical officer Clemens (Charles Dance, of Space Truckers). We will eventually learn that the prison was officially closed down years ago, but that a group of inmates led by a murderer named Dillon (Charles S. Dutton, from Cat’s Eye and Mimic) had gotten religion somewhere along the way, and requested that they be allowed to remain on Fury 161 to continue their penance. Really, it’s just an excuse to retain material from an earlier version of the screenplay, in which the setting was a monastery rather than a prison. But religious retreat or lockup, it’s still an unwelcome disruption so far as Andrews and Dillon are concerned when their colony suddenly has to contend with a woman who looks like Sigourney Weaver at the apogee of her sexual magnetism falling out of the sky to land among a bunch of men who have not seen a human female in person for a matter of decades. It’s going to be quite some time before the next supply ship arrives, too, so there isn’t much the superintendent can do about the situation except hope that Ripley stays in her interrupted-hypersleep coma until there’s somebody around to give her a lift home.

Yeah, well this would be a short, boring movie if Andrews got what he wanted, wouldn’t you say? Not only does Ripley swiftly regain consciousness, but she obstinately refuses to cooperate with the prison staff’s plan to keep her out of sight. Naturally, the first thing she wants upon awakening is news of Newt, Hicks, and Bishop, and when she hears about their deaths, the next thing she wants is an autopsy on both humans to ensure that their demise had nothing to do with parasitic space monsters. However, Ripley remembers well how her alien tales were greeted back home at the inquest into the Nostromo incident, so instead she feeds Clemens some cock-and-bull story about a cholera epidemic in the hope of scaring him into cutting open the corpses’ chests. Clemens goes along with it, but he obviously recognizes that Ripley isn’t telling him something. There’s no sign of either cholera or baby monsters inside Newt or Hicks, so Ripley has exactly one thing to feel good about now.

On the other hand, the reason Newt and Hicks are clean is because the face-hugger that might have impregnated one or the other of them is still alive aboard the EEV. The first suitable host it finds on Fury 161 is the last of the prison’s guard dogs, and the first victim of the adult creature that hatches from the dog’s body is its de facto handler, Murphy (Christopher Fairbank, from The Fifth Element and The Bunker). It isn’t obvious what happened to the dead man, though, because Murphy was sweeping the dust from an air main when the alien got him, and his body was chewed to pieces by the ventilator fan. Nevertheless, the bare fact of a death in an air shaft is enough to get Ripley thinking about her favoritest species in the whole wide universe, and she surreptitiously salvages the mission recorder from the EEV with the intention of checking it for signs of alien activity aboard the Sulaco while she was in hibernation. That plan founders when she discovers that the superintendent’s office contains the only working computer on the whole damn planet. (In point of fact, the office and the medlab between them contain very nearly the only working anything on the whole damn planet.) Thus thwarted, Ripley digs what’s left of Bishop (Lance Henricksen again) out of the colony’s junkheap, gets him sort-of working again, and has him access the data on the recorder. Bits o’ Bishop confirms the presence of a face-hugger aboard the Sulaco, pretty well making Ripley’s day— truth be told, the gang-rape she narrowly escapes a few moments later probably bothers her less than the news that there’s almost certainly an alien loose on Fury 161. Dillon bails her out of the former trouble (he can control his men much more effectively than Andrews or Aaron), but only she has the knowledge necessary to come to grips with the latter.

Obviously Andrews, Aaron, and Clemens will have to be told. Clemens trusts Ripley enough by now that he could plausibly be expected to believe her. Aaron is little more than a yes-man for the superintendent, and will surely agree with whatever verdict Andrews reaches. That makes Andrews the one to convince, and when the time comes, he proves as pig-headed and unimaginative as the company men back home. Even when the alien begins claiming more victims, Andrews prefers to believe that Golic (Queen of the Damned’s Paul McGann), the one man who witnesses an attack and lives to tell the tale, is really the culprit instead. (The obviously unhinged state of Golic’s mind in the aftermath renders such self-delusion easy enough to maintain.) The boss-man finds it rather harder to argue, however, when the creature drags him up into the mess-hall ceiling and kills him— and because it happens in full view of just about everyone else in the colony, the slaying of Andrews neatly rules out the possibility of anybody else picking up the scoffing where he left off. Unfortunately, Clemens is killed at about the same time, leaving the dim-witted Aaron the sole representative of legitimate authority on Fury 161. Ripley and Dillon will therefore be effectively on their own in organizing the effort to combat the alien, and the odds against them will be even longer than those Ripley faced aboard the Nostromo, for there isn’t a single weapon more formidable than a piece of cutlery or a farming implement anywhere in the colony. Furthermore, the strange reluctance of the alien to do any harm to Ripley stems from motives much more sinister than the size of Sigourney Weaver’s paycheck or the position of her name in the opening credits.

The most immediately obvious thing about Alien3, and the foremost reason for its inferiority to the preceding films, is the extent to which its creators were content merely to do the original movie over again in a new setting. Aliens did its share of reiterating, too, but its repetitions were largely confined to the final act, and James Cameron made nearly every one of them his own, whether by tweaking a few significant details of the recycled situations or by approaching them via a substantially different set of genre assumptions. Alien3, in contrast, breaks but one bit of new ground, implying that the worker aliens borrow part of their adult genomes from the organisms in which they incubate, and confirming that the queen and worker varieties are intrinsically different, rather than developing one way or the other due to environmental factors in the manner of female honeybees. Although I confess that it gives me a little charge to receive another piece of support for a pet theory of mine (this is not the place to bore you with my xenobiological speculations, but it concerns the aliens exhibiting a genetic condition called haplodiploidy, which is common among eusocial insects on Earth), that is a tiny crumb indeed in comparison to the vast enrichment of Alien’s fictional universe that we were given the last time around— especially when Alien3 is so slipshod in how it uses and interprets what we already know from its predecessors. Weyland-Yutani is back to being an all-powerful Evil Corporation, a major step backward from the more nuanced and believable regime of individual nefariousness enabled by institutional irresponsibility implied in Aliens. The symptoms of alien impregnation are now variable in ways that can be explained only in terms of plot convenience, an extremely disappointing state of affairs for an entry in a series that had previously distinguished itself by its consistency in most important respects. Ripley’s rather mercenary use of her sexuality to secure the loyalty and support of Clemens seems, if not necessarily out of character, then certainly insufficiently motivated, more an artifact of some producer’s dissatisfaction with the absence of romance from the series thus far than an organic part of this particular story; that it comes across as even potentially defensible is a testament to Sigourney Weaver’s flexibility and effectiveness as an actress. Combine that inattention to detail and willingness to accept the pedestrian with a screenplay that returns to the old recipe of nearly helpless humans stalked through futuristic sets by a single unearthly monster, and you really are left with nothing at all beyond the reheated leftovers of Alien. We’d already had a decade’s worth of that from various competitors and wannabes by 1992, so despite the advantages that came with a big budget and major-studio backing (and despite the smaller advantage that comes with a shaven-headed Sigourney Weaver taking a shower on camera), Alien3 remains an overwhelmingly inessential film.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact