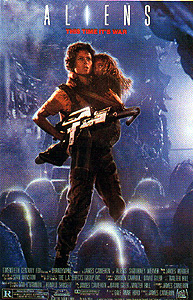

Aliens (1986) *****

Aliens (1986) *****

Things moved a little slower in Hollywood 30 years ago, and while decision-making was no less mercenary then than it is now, it was perhaps a bit less systematically so. If Alien had been made today, there’s every chance that 20th Century Fox would have had a treatment for a sequel in hand by the time the prints were ready for shipping to theaters, so that pre-production could begin at once in the event that the first film made money. But in 1979, automatic sequels were not yet part of the paradigm, and even after Alien had proved itself a success, the studio didn’t begin seriously contemplating a sequel for several years. Not until late in 1983 did the ball really start rolling, when James Cameron, having been told that an Alien sequel was under consideration, pitched a repurposed version of a sci-fi treatment he’d written during his New World Pictures days. Remarkably, Fox liked Cameron’s idea so much that they agreed to put the project on hold for him until he had finished with The Terminator— a delay which proved fortuitous anyway by providing an opportunity to settle some contentious salary negotiations with Sigourney Weaver, who was by then a much bigger name than she had been in the late 1970’s.

Even without the monetary wrangling to impose delays, it’s easy enough in retrospect to see why the studio heads were willing to wait around for Cameron’s schedule to open up. In contrast to what one usually expects from a mid-80’s sequel, he had a lot more in mind than just making the old movie over again with a bigger effects budget. Cameron in those days was an action director first and foremost, and his plan was to follow Ridley Scott’s sci-fi horror film with something approximating a sci-fi war movie with monsters standing in for the enemy army. The title itself— Aliens— elegantly suggests where the difference will lie; if just one of those creatures from the cavern beneath that wrecked alien starship could exterminate the crew of the Nostromo in less than 24 hours, imagine what an entire nest of the things could do!

When we last saw Ellen Ripley (Weaver once again— and notice that her character gets a first name this time around), she was drifting off into hypersleep aboard the Nostromo’s shuttlecraft/lifeboat after blowing up both the ship and the automated ore refinery it was towing in a last, desperate attempt to destroy the seemingly indestructible monster her crew— the rest of them all dead now— had picked up (by accident, or so they believed) during a detour to investigate the radio signals emanating from an unexplored moon. Now we see her tiny craft being boarded by a deep-space salvage crew, who are rather surprised to find her still alive within her hypersleep module. They’re not half as surprised as Ripley herself is when she is brought back to the space station Gateway (apparently in terrestrial orbit), and informed that she’s been adrift in the interstellar void for 57 years. That jarring news comes from Carter J. Burke (Paul Reiser), an employee of the same company for which Ripley used to work sailing the spaceways (and which is also now given a proper name— Weyland-Yutani, supposedly the closest the filmmakers could come to Leland-Toyota without inviting a lawsuit). Burke’s bosses are very interested in talking to Ripley, particularly regarding why she blew up her ship all those years ago. Corporate bureaucracies have long memories for losses of that magnitude, it would seem, even in the distant future. Ripley’s tale is not well received. No species even faintly resembling the one she describes finding on moon LV-426 has ever been documented anywhere, and so far as is known, LV-426 is completely devoid of indigenous life. Nor was there any trace of an alien lifeform aboard Ripley’s lifeboat. So with her crewmates dead and the Nostromo vaporized in deep space, there is not one single shred of evidence to support Ripley’s story, and at least one humongous reason to discount it entirely— LV-426 has been under colonization by terraformers for some considerable while now, and no one among the 60-odd families living and working at the atmosphere processing plant there has ever said anything about a crashed alien spaceship or silicon-skinned, acid-bleeding, esophagus-parasitizing monsters. Ripley loses her Weyland-Yutani astronaut certification, and the only work she can find is down on the space docks, driving forklifts and power-suit loaders, a bum deal for her all around. Then there are the recurring nightmares and the post-traumatic stress disorder to deal with, to say nothing of having to adjust to the idea that the children of all the people she used to know are now shopping for condos in retirement communities.

A few weeks later, Burke comes to see Ripley at her apartment. Curiously, he’s brought along a Lieutenant Gorman (William Hope, from Hellbound: Hellraiser II and Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow) of the Colonial Marine Corps. It seems there’s been some trouble on LV-426, and suddenly all the Weyland-Yutani bigwigs are much more interested in Ripley’s space-monster stories. It’s nothing as firm as a creature sighting, or even a report that somebody stumbled upon Ripley’s alien ghost ship, but given her report, the sudden, unexplained loss of all contact with the colonists is arguably a great deal more alarming than either of those possibilities. The bosses want to send Gorman out to LV-426 with an expeditionary force, and Burke has been authorized to offer Ripley her old job back in exchange for her services as a technical advisor. She, after all, is the only human on Earth who is even passingly acquainted with the species Gorman’s marines might be facing. Ripley initially refuses to have anything to do with the plan, but the more she thinks about it, the more appealing she finds the prospect of getting to witness the extermination of the aliens with her own eyes. She calls Burke back, and tells him she’s in.

The space-navy assault ship Sulaco is, if anything, an even more impressive piece of hardware than the Nostromo and its refinery, what with those massive gun turrets and that forest of what I take to be missile silos bristling from its bow. However, the force embarked aboard this formidable vessel suggests just how un-seriously the authorities take Ripley’s testimony about the LV-426 species even now, for it consists of but one lousy platoon, and three of the marines— Gorman himself and dropship pilots Dietrich (Invasion Earth: The Aliens Are Here’s Cynthia Dale Scott) and Spunkmeyer (Daniel Kash, from Nightbreed and Diary of the Dead)— have duties that preclude them doing any actual fighting. In terms of boots on the ground, it’s just squad leaders Sergeant Apone (Al Matthews, of The Fifth Element and Omen III: The Final Conflict) and Corporal Hicks (Michael Biehn, from The Seventh Sign and The Abyss), squad heavy weapons operators Vasquez (Jenette Goldstein, from Near Dark and Terminator 2: Judgment Day) and Drake (Mark Rolston, from RoboCop 2 and Scanner Cop), and five regular grunts: Hudson (Bill Paxton, of Predator 2 and The Terminator), Frost (Ricco Ross, of Project Shadowchaser and Octopus), Ferro (Collette Holler), Wierzbowski (Trevor Steadman), and Crowe (Tip Tipping). (Note, incidentally, that tactical symmetry would seem to demand one more marine, for two five-person squads.) Burke is along for the ride as well as Ripley, and the Sulaco also has a civilian science officer by the name of Bishop (Lance Henriksen, from The Horror Show and The Pit and the Pendulum). Bishop’s presence on the ship is a sore point for Ripley, because Bishop is a synthetic (“I prefer the term, ‘artificial person,’ myself.”), and Ripley, as you may recall, has not had the best of luck with android science officers. Bishop and Burke both assure her that there have been enormous strides in behavioral programming in the intervening five decades, but all things considered, I think we can forgive Ripley for not buying it. Nor, for that matter, does she have much confidence in Gorman, whom she regards as the worst sort of fool— the kind who unshakably believes himself to be completely on top of whatever situation he’s in, no matter how forcefully reality might contradict him. And in perhaps the gravest portent for the mission’s success, the other marines seem to agree with Ripley’s assessment of their inexperienced new lieutenant.

Dietrich lands one of the Sulaco’s two dropships (fearsome vehicles resembling transatmospheric descendants of the Vietnam era’s Huey utility helicopter, but armed more like the later Cobra and Apache attack choppers) on the margin of the colony complex, at which point the rest of the team drives up to the main entrance in an armored personnel carrier. Gorman, Burke, Ripley, and Bishop remain in the APC, while Apone and Hicks lead their respective squads on a sweep of the main living spaces. To all appearances, the colony is deserted, and the damage the marines find all over the interior strongly suggests that there was some fierce fighting before it got that way. Most notably, the soldiers find numerous places where the walls and floors are burned or melted through, exactly as they would be if one of Ripley’s acid-blooded aliens had been killed there. There isn’t a single body to be seen, though, human or alien. Gorman declares the area secured, and he and the three civilians go inside to begin a more detailed investigation. So far as can be determined, the colonists must have barricaded themselves into a small and easily controlled section of the complex, consisting of the medical lab and the main control suite. These areas have suffered comparatively little damage, and contain signs of more recent habitation than the rest of the colony. The med-lab also offers incontestable proof of Ripley’s account, for it houses several specimens of the second stage in the aliens’ life-cycle, the hand-like organisms that deposit the endoparasitic embryos— two of them still alive, too. Bishop begins dissecting one of the creatures, while Gorman and Burke set their minds to figuring out whither the colonists might have disappeared.

That’s when one of the marines guarding the perimeter picks up something on his motion tracker. The soldiers spring to alert status, but it’s no space monster sneaking around in the utility tunnels outside of Operations. Instead, the intruder turns out to be a little girl (Carrie Henn) who has obviously had a tough time of it— she looks like a homeless, deinstitutionalized mental patient, and she acts like she was raised by wolves. The marines, burdened with their assault rifles and body armor, are unable to apprehend her, but Ripley succeeds, cornering the girl in the garbage-collection compartment where she has apparently been living. Getting the girl to talk takes some doing, though again Ripley manages. Her name is Rebecca Jorden, but she prefers to go by Newt; so far as she knows, she’s the last person alive out of the entire colony. Actually, that isn’t quite accurate, for Private Hudson (evidently the platoon’s electronics expert) is able to detect a sizable concentration of vital signs in a compartment beneath the main cooling unit for the nuclear reactor that powers the atmosphere processor. The marines head in to perform the rescue they came for, and matters swiftly go catastrophically awry. The colonists have all been cocooned by the aliens in close proximity to a corresponding quantity of their big, leathery eggs, and those of the terraformers who still live have been impregnated with embryos. The area is also crawling with adult aliens, but because their skins are virtually indistinguishable from the resinous secretions with which they line their lairs, and because their body temperature is too low for them to present a detectable infrared signature, they are all but invisible to anything but the motion trackers until they are within arm’s or jaw’s or stinger’s reach of their prey. Furthermore, the makeshift hatchery’s position underneath the reactor’s coolant system means that the marines can’t use the armor-piercing weapons capable of killing the creatures without risking a core meltdown. The result is an absolute slaughter. By the time Ripley seizes control from the thoroughly overwhelmed Gorman and organizes a withdrawal from the scene of the battle, only Hicks, Hudson, and Vasquez remain alive among the fighting marines, Gorman is incapacitated with a concussion, and the APC is an inoperative wreck. Meanwhile, one of the aliens finds its way aboard the dropship, and dispatches Dietrich and Spunkmeyer shortly after they take off to collect the survivors. That leaves Ripley, Burke, Bishop, Newt, and the last four marines stranded on LV-426 with no equipment save that which can be salvaged from the APC as night comes on, bringing with it the mass awakening of the primarily nocturnal aliens. And because of all that shooting underneath the coolant plant, the tattered remnant of Gorman’s expeditionary force will be facing seemingly certain death in a nuclear meltdown even if they manage to survive the aliens’ onslaught.

If Aliens has a weakness, it’s the somewhat excessive similarity between its final act and that of its predecessor. It may be an accidental reactor-core meltdown rather than a deliberate attempt to eliminate the aliens by blowing up their lair, but the protagonists’ efforts to escape from LV-426 still play out against the countdown to an unendurably vast explosion. Ripley postpones her flight to save Newt instead of Jones the cat, but either way, she winds up spending the final minutes before the earth-shattering kaboom on an un-planned-for rescue mission. The climactic escape again provides only a temporary reprieve due to one of the aliens stowing away aboard the small craft Ripley and her remaining companions use to take their leave of the doomed colony. Aliens even resets the terms of the final battle to Alien’s one-on-one by introducing the alien queen, a solitary threat that outclasses the heroes’ enhanced combat capabilities just as completely as the original creature outclassed the Nostromo crew’s. There are enough detail differences at each step of the way that the overarching sameness isn’t a major defect, but the familiarity of the proceedings remains quietly nagging nonetheless.

In every other respect, however, Cameron and company have succeeded more than admirably in following up a modern classic, creating one of those vanishingly rare sequels that deserve classic status in their own right. Aliens is really the movie that fulfilled the promise of The Terminator, to a much greater degree than the latter film’s own overblown, ill-conceived successors. It combines a confident enlargement in the scale of the action with the discipline instilled by recent experience with much lower budgets. Whereas later on, Cameron would display a marked tendency to ramble, and to allow himself to be counterproductively seduced by newly available technologies, at the time of Aliens, he was still committed to wowing audiences the old-fashioned way, with taut scripts, crisp pacing, and the careful manipulation of the viewer’s adrenal glands. A comparison with Alien is especially instructive here, for it demonstrates something the young James Cameron understood that has been lost on all too many other directors: a great action movie is every bit as dependent upon suspense as a great horror film. Both genres trade heavily on situations that, in the real world, would place intense demands on the fight-or-flight reflex— surely a battlefield outdoes any monster or murderer when it comes to inspiring raw, pants-shitting terror! Remarkably, there are more than a few instances of Cameron using exactly the same suspense-generating mechanisms as Ridley Scott had, and yet achieving a markedly different (albeit obviously related) effect. For example, compare the scene from Alien in which Dallas and the creature stalk each other through the Nostromo’s air ducts to the one here in which a small army of the things advance against the makeshift fortifications Ripley and the marines have erected to seal off Operations. In both cases, the oncoming menace is invisible to the threatened characters due to the aliens’ canny exploitation of the setting, their approach heralded only by the blips on the screens of the humans’ motion-trackers. Both scenes stretch the buildup as far as it will go, with the unseen monsters drawing steadily nearer while their prey struggles to figure out how in the hell they’re concealing their advance. The difference lies in what follows that buildup— the sudden and effectively uncontested demise of Captain Dallas in the horror-oriented Alien versus the pitched battle between humans and monsters in the action-focused sequel. A similar contrast obtains between the two movies’ otherwise very similar climaxes. When Ripley faced that first worker alien in the cockpit of the Nostromo’s lifeboat, she saw no alternative but to outwit it, seeking some means of destroying it without risking a direct confrontation. In Aliens, she fights the queen hand-to-hand, using one of those power-suit loaders she learned to drive on the Gateway docks to even the odds between her and the huge, heavily armed creature.

The other way in which Aliens builds on the legacy of The Terminator as well as that of Alien concerns the obvious care Cameron once again took in elucidating the movie’s fictional world, this time including a light dusting of retrospective social commentary sprinkled over the story— quite possibly by complete accident. Aliens shows a bit more of the society of future Earth than its predecessor had, and again the most interesting details are left to stand on their own in the background, for the audience to make of them whatever they will. The Weyland-Yutani company, for example, appears not so much evil as homicidally negligent now that we get a closer look at it. There seems to be no institutional memory of Special Order 937, or of the never-discussed discovery that must have underlain it. Far from seeking to use the aliens as a basis for bioweapons research, the current generation of Weyland-Yutani executives refuse to believe that the creatures exist in the first place. Burke, though he plays a role analogous to that of Ash in the earlier film, does so purely on his own initiative, in response to the information in Ripley’s report; whatever geniuses at the company’s weapons division wanted the LV-426 organism brought home 57 years ago must have taken everything they knew with them into retirement after the plan to divert the Nostromo from its original mission ended in calamitous and expensive failure. We also get a few oblique hints regarding the political structure of Earth at whatever date this is supposed to be. Although corporations like Weyland-Yutani are clearly very powerful, they have obviously not replaced governments as we currently understand them, or there would be no power struggle between Burke and Corporal Hicks after the mission goes horribly haywire at first contact. Also, some manner of political separation must still exist between the Anglo and Latino sectors of the Americas if one of Private Hudson’s quips about Vasquez is to make any sense. But the most significant aspect of Cameron’s world-building enterprise in Aliens is surely his treatment of the Colonial Marine Corps itself. Inexperienced and ineffectual junior officers leading resentful and frequently unprofessional foot-soldiers into pointless slaughter at the hands of an enemy whom the higher-ups have grossly underestimated due to ideological blindness and almost willfully faulty intelligence— simply put, this is the Vietnam War’s US military on its worst day, translated into sci-fi terms. Aliens thus takes a curious place in the pattern formed by more forthright 1980’s Vietnam movies ranging from Full Metal Jacket and Platoon, through Hamburger Hill and Good Morning, Vientam, and all the way down to Rambo: First Blood, Part 2 and Missing in Action. Mind you, I don’t really believe that this was something Cameron set out to do. Rather, I think it’s more a side effect of Hollywood having developed an almost feverish fixation on the war during the mid-80’s, coupled with the fact that Vietnam was still the most recent example of the American military’s conduct in combat— generals aren’t the only people who are always fighting the previous war. For that very reason, though, Aliens may actually have more to tell us about how Vietnam-derived assumptions continued to color American thinking about what could be expected in a limited war than any of its more obvious brethren. Even in a far-flung future when sleeper ships navigate the interstellar gulfs without guidance from human operators, and despite weapons that give a single man the firepower of an entire squad of William Westmoreland’s army, as clever and imaginative a filmmaker as James Cameron still couldn’t think beyond the haplessness and dysfunction of the Vietnam era.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact