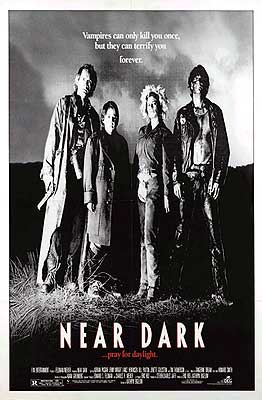

Near Dark (1987) ****

Near Dark (1987) ****

In 1987, after thirteen years of basically not giving a shit, I suddenly developed an intense interest in vampires. It was entirely the fault of two movies that came out that year, The Lost Boys and Near Dark. Those films changed my mind about the undead by abandoning all the baggage of the past hundred years to present a kind of vampire that Bram Stoker would barely have recognized. The furthest thing from decadent Continental European noblemen, these bloodsuckers were thoroughly modern, thoroughly American, and thoroughly low-class. Although The Lost Boys was the one that really fired my imagination, with its vaguely punky street hoodlum vampires (a natural source of appeal for a kid beginning to turn vaguely punky himself), it was obvious to me even then that Near Dark was the superior film. Furthermore, its brutal undead rednecks presented an even starker challenge to the genre’s status quo.

Teenaged 20th-century cowboy Caleb Colton (Adrian Pasdar, of Solarbabies) lives in the remote map-speck settlement of Fix, Oklahoma, with his veterinarian father, Loy (Tim Thomerson, of Zone Troopers and Metalstorm: The Destruction of Jared-Syn), and his little sister, Sarah (Marcie Leeds, from Wheels of Terror and Out of the Dark). No one ever mentions what became of the kids’ mom. One night, while he and a couple of his buddies are out on what passes for the town, Caleb spots a breathtakingly beautiful girl (Jenny Wright, of I, Madman and The Lawnmower Man), and drops everything to go flirt with her. It’s a strange evening the boy has in store for him. Although Mae seems to enjoy his company, and to want as much of it as possible, she’s visibly quick to shut down any attempt on his part to move things in a physical direction— except that she also visibly wants that just as much as he does, maybe even more. Caleb’s horse is terrified of her (so much for that approach to a romantic evening out on the range), which she says is pretty much normal for her and animals. She talks oddly, too, rhapsodizing over the brightness of the night and the loudness of the silence. When Caleb remarks that he’s never met a girl like her, she agrees in all seriousness, and then says the weirdest thing of all. Pointing to one of the stars, she tells him that the light leaving it will take a billion years to reach Earth— and the reason he’s never met a girl like her is because she’ll still be here to see that light when it arrives. Then, without warning, Mae begins panicking over the time, and demands that Caleb take her home at once. Evidently it’s vitally important that she not stay out past sunrise. The sky is gray with predawn twilight as the pair approach the trailer park which Mae identifies as their destination, but Caleb abruptly stops his pickup truck and turns off the engine maybe a hundred yards from the entrance. He says he’s not driving another inch until Mae kisses him. Once again, he gets more than he bargained for. Mae climbs into Caleb’s lap, and begins making love to his face with her lips. And then she bites him on the neck, hard enough to draw blood. With that as her parting shot, the enigmatic girl jumps out of the truck and races off at top speed into the trailer park, leaving Caleb to ponder what the fuck just happened. He’ll have plenty of time to think it over, too, because now his truck won’t start, and it’s a long way back to the Colton farm.

The sun is on its way back down again by the time Caleb gets within sight of home. Partly that’s because he had just that far to walk, but it’s also because round about midday, he started feeling sicker than he’s ever been before in his life, slowing his progress to an almost literal crawl. Loy and Sarah are justifiably alarmed when they see him staggering across their outermost expanse of fallow fields, but what happens next is even more alarming. A Winnebago, its windows all blacked out with duct tape and aluminum foil, pulls up on Caleb from behind, and whoever’s inside scoops the ailing boy up and makes off with him. The other two Coltons will not find the local law-enforcement officials terribly helpful in the immediate aftermath of the kidnapping.

You’ve probably guessed by now that Mae had something to do with Caleb’s abduction, and you’ve surely also figured out approximately what her deal is. What wasn’t apparent previously is that she’s just one of a whole pack of vampires who roam the Southwest like a band of malevolent Gypsies. Their leader is a scar-faced hard-ass called Jesse Hooker (Lance Henriksen, of Hard Target and Nightmares). He won’t say exactly, but he’s been at this for many years: “Let me put it this way— I fought for the South. We lost.” Jesse’s consort calls herself Diamondback (Jenette Goldstein, from Aliens and Star Trek: Generations); she throws a mean knife, and she’ll happily put one in you if you try to mess with her brood. Filling the de facto role of firstborn son is Severen (Bill Paxton, from Boxing Helena and Streets of Fire), who was probably meaner than a rabid weasel even before he became a vampire. And as for “little brother” Homer (Joshua Miller, of Halloween III: Season of the Witch and Class of 1999), don’t let his appearance fool you. Like another juvenile bloodsucker of our acquaintance would say, he’s been thirteen for a long time. Given their druthers, Jesse and the others would kill Caleb right now like Mae was supposed to last night, but the boy is turned by this point, and vampires killing vampires is apparently just not done. But while the pack may be stuck with Caleb, they expect him to start pulling his own weight after a few nights’ orientation. I gather there’s no taboo against vampires throwing vampires out on their asses to shift for themselves if they can’t get with the program.

Near Dark’s second act follows two parallel courses. On one side, it shows Loy and Sarah growing disgusted with what they perceive as official inaction, and setting out on their own to find Caleb and his kidnappers. Their search will take them all over Oklahoma, Texas, and Kansas, chasing down sightings of a teenager meeting Caleb’s description. And on the other, we have the frequently fraught process whereby Caleb reconciles himself to his condition, and earns the tentative trust and respect of Jesse and his clan. Understand that neither of those things are what the boy wants at first. He’s no killer, and isn’t interested in becoming one. Furthermore, apart from Mae, he finds his fellow vampires nothing but horrifying. For their part, the vampires (again, excepting Mae) have little patience for the new guy’s crisis of conscience, and they’re really not fond of the way his inability to complete a kill keeps opening them up to trouble. But the inconvenient fact remains that Caleb is a vampire now, and as the weeks pass, he comes increasingly to see that being undead is not without its advantages. Then, of course, there’s Mae, whom Caleb can’t help loving no matter how many truck drivers or night shift diner waitresses he sees her exsanguinate.

The turning point comes when the sole survivor of a massacre at a dive bar— a survivor whom Caleb was supposed to finish off— brings the full strength of some redneck desert-county police department down on the vampires while they sleep away the daylight hours in a middle-of-nowhere motel. Heavily outgunned, and with every bullet the cops fire admitting a ray of deadly sunlight into their flimsy bungalow, Jesse and company figure the game is finally up. But then Caleb does something dementedly brave. Wrapping himself in a wool blanket to keep as much of the sun off of him as possible, he hurls himself through one of the windows and runs to the gang’s van, catching bullets and crisping to charcoal all the while. Then he fires up the engine, and rams through one wall of the bungalow, giving the besieged vampires an avenue of escape after all. Whatever they think of his squeamishness in the face of murder, that rescue convinces Jesse, Diamondback, Severen, and Homer that Caleb is alright. And for a while, it looks like he’s going to become one of the clan for real. At the next motel where they stop, however, Caleb’s new family unexpectedly encounters his old one. Loy and Sarah’s search has finally led their path and Caleb’s to intersect, leaving the undead boy with a whole lot of heavy decisions to make.

My DVD copy of Near Dark is the edition from Studio Canal and Lionsgate, released in 2009. That’s the one with the pathetic Photoshop cover art designed to trick you into thinking Near Dark is a direct-to-video Twilight rip-off, and ridiculous as that is, I kind of love it. I imagine thirteen-year-old girls hungry for more vampire-on-human romance picking up this movie on the basis of that cover art and having their minds blown. Near Dark was mind-blowing enough at that age coming to it for another fix of The Lost Boys like I did. Either way, you’d be getting what you wanted from this movie, albeit on terms completely unlike what you expected. Near Dark really is a vampire-on-human romance, after all, just as it really is the story of a teen boy falling in with a pack of modernized vampires and having to weigh the allure of their power against the demands of his conscience. But Near Dark adds something to the mix that neither Twilight nor The Lost Boys has: its vampires are scary. Better yet, what makes them so has little to do with blood-drinking, enhanced strength, or ability to shrug off injuries that would instantly kill a human. Diamondback is like an undead Ma Barker. Severen is the apotheosis of the crazy redneck who likes to fight. Homer is a dirty old man trapped in a pubescent body, utterly unpredictable because of his constant need to prove himself. And Jesse is just a dead-eyed psychopath, a man whose every word and gesture alludes to the incalculable trail of bodies stretching out behind him. They’re the most terrifying horror movie vampires of their era because they’re among its most terrifying horror movie people.

At the same time, though, Near Dark’s vampires are charismatic as hell, and as seductive as any others of their kind going back to John Polidori’s Lord Ruthven. Let me emphasize, too, that I’m not talking just about Mae, who is portrayed as having a core of goodness to her that four years of preying on humans hasn’t yet effaced. Even the thoroughly corrupt and evil Jesse has a sort of musky virility about him, unrelated to sex appeal in the ordinary sense. It’s the attraction of sheer, savage, animal power. If you hung around with this bunch, if you could somehow be like them, then nobody would ever fuck with you again. I can’t imagine there’s anybody alive who hasn’t wanted that from time to time. So the choice for Caleb is harder than you might expect, even with his sturdy, small-town values (in the idealized sense of that phrase) bearing down on one side of the scale. To be invincible, to be unassailable— maybe that’s worth also being a monster. Again, that’s the same choice faced by Michael in The Lost Boys, but the options are much starker in Near Dark, with its vastly more menacing vampires, and without the gay metaphor to confuse the issue.

Mind you, Near Dark’s version of the scenario also carries more weight just because this movie was directed (and partly written) by Kathryn Bigelow instead of Joel Schumacher, and because she was able to rely on the ready-made ensemble of Lance Henriksen, Bill Paxton, and Jenette Goldstein, all of them fresh from the set of Aliens. In the years since this, her breakout film, Bigelow has become a pretty big deal, and as is generally the case with true top talent, the magnitude of her ability is already visible here. Near Dark shares with the other vampire movies of the 80’s an emphasis on the visual, but its look is not that of its competitors (even as the score by Tangerine Dream does its level best to convince you that you ought to be seeing the usual MTV-isms). Bigelow and co-writer Eric Red actually wanted to make a Western, but they knew there was no profit in that idea. So instead, they made the horror film that Sergio Corbucci might have, had he decided for some reason to offer a riposte to Billy the Kid vs. Dracula. Instead of fog and neon, Near Dark gives us dust and sweat and rotgut whiskey— a look and feel to match the Cramps cover of “Fever” that plays on the jukebox while Severen high-kicks the bartender’s throat open with the spurs on his cowboy boots. Near Dark also shows the knack for working with actors that subsequent Bigelow movies would prove to be one of her defining traits as a director. As I said, Henriksen, Paxton, and Goldstein practically were family by this point, having worked together for so long on Aliens, but the performances Bigelow got out of Adrian Pasdar, Jenny Wright, and Joshua Miller— all of them quite near the beginnings of their careers— are scarcely less impressive. And Tim Thomerson does more with this smallish part than he ever managed as the star of Charles Band’s inexplicably endless Trancers series. Thus, once again, do I rejoice at that stupid, hacky, aggressively cheap mock-Twilight cover. Because of it, somewhere in the world, a curious teenager is being hoodwinked into discovering a minor classic even as we speak.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact