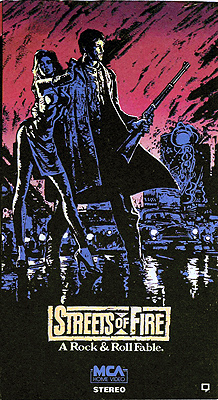

Streets of Fire/Streets of Fire: A Rock & Roll Fable (1984) ***

Streets of Fire/Streets of Fire: A Rock & Roll Fable (1984) ***

I would define a cult movie as a film that enjoys little if any commercial success in a given territory upon its initial release, but which subsequently (and in most cases very gradually) acquires a fair-sized following of fans whose loyal ardor makes up for their modest numbers. And by extension, I would say a cult filmmaker is one whose reputation (at least in certain circles) rests primarily on a foundation of cult movies. Most behind-the-camera movie careers last for decades, of course, and most writers, directors, and producers will face their shares of both success and failure over all that time; meanwhile, the nature of cult films is such that they frequently have more staying power than any but the biggest mainstream hits. As a consequence, it is well within the realm of possibility for one person to start off as a cult figure before evolving into a big-name hit-maker and vice versa. In fact, that phenomenon is the only way I can think of to account for Walter Hill. Hill, in his 1980’s heyday, was one of the driving forces behind that decade’s tiresome boom in violent buddy-cop movies, primarily on the strength of his hugely popular Nick Nolte-Eddie Murphy vehicle, 48 Hrs. I ask you, though: when was the last time you even thought about 48 Hrs., let alone Another 48 Hrs. or Red Heat? Blockbuster though it was at the time, Hill’s biggest score is just another old movie these days, and in the unlikely event that you find someone outside the industry who still recognizes the name Walter Hill, I can virtually guarantee you that they will know him more for a different and far less lucrative aspect of his career. Sprinkled in among the conventional crime thrillers and retro-Westerns that comprise the bulk of Hill’s output are a handful of extremely idiosyncratic action movies that are about as culty as it gets. The most notorious of these is undoubtedly his late-70’s youth-gang fantasy, The Warriors, but running that film a close second is one that is in some ways even more peculiar. You will doubtless have guessed by now that I’m talking about Streets of Fire.

What we have here is among the most eccentric manifestations of 1980’s pop culture’s fascination with urban decay and societal collapse, but as with The Warriors, a mere synopsis of Streets of Fire’s plot just barely hints at the true nature of that eccentricity. In a setting described only as “another time, another place,” Ellen Aim (Diane Lane, from Judge Dredd and Untraceable), lead singer of Ellen Aim and the Attackers, is kidnapped right off the stage at the Richmond Theater by a biker gang called the Bombers. Evidently it was the much-anticipated homecoming gig of a long and far-flung tour. Although Ellen’s release would obviously be worth a great deal to her boyfriend and manager, Billy Fish (Rick Moranis, of Ghostbusters and Little Shop of Horrors), extortion does not appear to be the Bombers’ aim. Rather, their chief, Raven (Willem Dafoe, from Shadow of the Vampire and Anamorph), harbors a personal fixation on the singer, and it scratches his itch for power and domination to keep her for a while as a plaything. As Raven puts it after he’s installed Ellen in an upstairs room at a rough nightclub in the lawless slum known as the Battery, “You act nice, you and me fall in love for a week or two, and I let you go. Nobody gets hurt.” Perhaps not. But who knows what nominally non-injurious degradations Ellen will have to suffer before Raven finally grows bored with her?

All is not lost yet, however. The diner across the street from the Richmond Theater belongs to a young woman named Reva Cody (Deborah Van Valkenburgh, from The Warriors and Phantom of the Ritz), and her little brother, Tom (Michael Paré, of World Gone Wild and Komodo vs. Cobra), is a major badass. An accomplished thief, brawler, and drag-racer, Tom recently finished a stint in the army, and now lives in Cliffside, supporting himself with a combination of petty crime and selling his services to those who urgently need somebody else’s ass kicked. Think of him as Snake Plissken, but with smaller hair and better depth perception. And as it happens, Tom used to date Ellen Aim back before her singing career took off and he joined the military. Reva sends her brother a telegram, asking him to come home and hinting at big trouble. Tom does indeed answer the summons, but he still carries enough lingering bitterness over the old breakup that he refuses to treat rescuing Ellen as anything more than just another job. (And yes, that does inevitably mean that the estranged pair will be in love again by the end of the second act.) Tom and Billy Fish negotiate the deal at Reva’s diner; for $10,000, Tom will spring Ellen from her captivity, but Fish (who knows the Battery well from his long experience as a show promoter— the best rock clubs are always in the worst neighborhoods) will have to tag along as Cody’s guide. Cody also ends up subcontracting to another vagabond ex-soldier, a woman called McCoy (Amy Madigan, from The Day After and The Dark Half), for more practical backup. (Incidentally, one of my favorite things about Streets of Fire is all the effort Hill devotes to establishing McCoy’s lesbianism without ever once uttering the word or violating mid-80’s taboos by putting her in a position to express romantic interest in another female.) The raid on Torchie’s (the bar where Ellen is being held) is only the beginning, though. For one thing, the ruckus Tom and company raise in the Battery is so great that not even the corrupt and demoralized cops who work the adjoining Ardmore district can ignore it, and those guys won’t be nearly as understanding as the tough-but-fair captain of the Richmond precinct (Richard Lawson, of Sugar Hill and Black Fist) if they catch up to Ellen and her rescuers. But more importantly, Raven wasn’t finished with Ellen yet, and he plausibly considers it an affront against his and his gang’s honor when Cody snatches her every bit as brazenly as Raven himself had. Raven, unlike the Ardmore cops, isn’t going to lose interest in Tom after the initial getaway, either. No, he’s much more likely to descend upon the Richmond district with the full force of the Bombers at his back, escalating the dispute over Ellen to the level of all-out war.

You see what I mean? To judge from the preceding two paragraphs, you’d think Streets of Fire was nothing more than another pedestrian takeoff on Escape from New York. To understand what makes it really special, you have to realize what Walter Hill means by “another time, another place.” A lot of people seem to assume that the setting is one of those post-apocalyptic futures that were so popular in the early-to-mid-80’s, and that looks at first glance like a reasonable enough interpretation. Whatever city we might take this funhouse-mirror version of Chicago to be has obviously not yet descended completely into barbarism, but it’s roughly as far along that road as Mad Max’s Melbourne. Appurtenances of civilization like mass transit, a police force, and a money economy are plainly in evidence, so we can tell that society is still functioning— it just clearly isn’t functioning very well when what used to be a major city’s industrial core has been completely surrendered to the control of criminals whose organizational style owes more to the Golden Horde than to the Mafia. And Raven is unmistakably a Toecutter/Lord Humungus figure, with his outlandish wardrobe (Black rubber overalls? Seriously?) and his penchant for theatrical gestures like challenging his enemies to duels with sledgehammers.

There’s more going on here than that, however, so that the superficially obvious reading of Streets of Fire as We Have Seen the Future, and It Sucks isn’t exactly right. Instead, the world of Streets of Fire would be better described as one where a crime-ridden dystopian future is happening concurrently not only with the 1980’s, but with the 1950’s and the 1930’s as well. Cody and McCoy look, dress, act, and speak like they wandered in from some hardboiled Depression melodrama pitting out-of-work factory hands against the mobsters who have taken over their neighborhood, and the persistence of 30’s-like prices for consumer goods is hinted at when McCoy ventures to prove her fitness to pay an all-evening bar tab by slapping a handful of loose change down on the counter. The automotive industry, meanwhile, is clearly frozen in the 50’s, with the cops all driving 1951 Studebakers, and the most recent motor vehicles to be seen anywhere (a Chevy Impala and a Buick LeSabre that each seem to have as many different owners as the Jeep in The Monster of Piedras Blancas) both dating from 1959. Similarly 50’s-bound are the greaser gang against whom Cody establishes his ass-kicking credentials upon his arrival in town, the doo-wop band whose tour bus Tom and the others commandeer on their flight from the Battery, and the mob of hopelessly square golf-pants-clad Richmondites who come to Cody’s aid in the final showdown with Raven and the Bombers. Come to think of it, even the racist Ardmore cops who make trouble for the Sorels (that doo-wop group I mentioned) are racist in a specifically 50’s way. The 80’s, meanwhile, are represented most vividly by Ellen Aim and the Attackers. Musically at least, Aim comes across as a female version of Meatloaf, all bombast, neon, and musical-theater pseudo-rock— which is only to be expected, given that both of the Attackers songs we get to hear in their entirety were written by Meatloaf Svengali Jim Steinman. The songs were recorded by another bunch of Steinman proteges called Fire Inc., although the band backing Ellen up onscreen is the Boston-based new wave combo, Face to Face (not to be confused with the later pop-punk band of the same name), whose frontwoman, Laurie Sargent, provides Ellen Aim’s singing voice. And last but not least, there’s a strong element of the 80’s aping the 50’s, as represented by the more up-to-date Motown-influenced sound the Sorels adopt when they come under Billy Fish’s management, by the Blasters (the retro-rockabilly act who are onstage at Torchie’s when Tom comes to Ellen’s rescue), and by the obscenely hypertrophic pompadour worn by McCoy’s nemesis, Clyde the bartender (Bill Paxton, of Near Dark and Weird Science). “Another time, another place” indeed.

Now you’ll notice the great emphasis I placed on music there. It isn’t for nothing that Streets of Fire bills itself as “A Rock & Roll Fable.” It would be an overstatement to call this movie a musical, but music plays every bit as big a part in it as it does in The Phantom of the Paradise or Rock ‘n’ Roll High School. We see Ellen Aim perform onstage twice, on television once, and once again in Tom Cody’s memories. The Sorels sing once in their original style on the bus ride through Ardmore, then again as the Attackers’ opening act in the final scene. Even the raid on Torchie’s is configured in such a way as to permit the Blasters two songs. It isn’t at all what one expects— or indeed normally wants— from a mid-80’s beat-’em-up/shoot-’em-up, and I gather that Streets of Fire’s not-exactly-a-musical status goes a long way toward explaining the lukewarm (at best) reception that greeted this movie when it was new, and which apparently put a stop to plans for a trilogy detailing the adventures of Tom Cody. In retrospect, though, it’s at least as vital a part of Streets of Fire’s strangeness as the unique and bewildering setting, and strangeness accounts for the lion’s share of this movie’s lasting appeal.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact