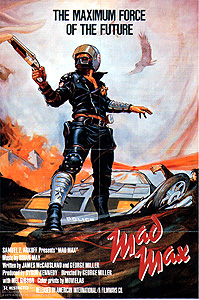

Mad Max (1979) ***½

Mad Max (1979) ***½

It isn’t very often that filmmakers from the Southern Hemisphere have much of an impact on the commercial cinema industry outside of their home countries. I mean, when was the last time you saw people lined up around the block to see the latest import from Peru or South Africa or Indonesia? Consequently, it was a watershed moment when Australians George Miller and Byron Kennedy knocked the action movie fans of the world on their asses with Mad Max. It put a previously unheard-of actor from New South Wales on the road to such gigantic stardom that he would one day be able to talk a Hollywood studio into releasing the world’s first fundamentalist Catholic gore movie. Its uncommonly aggressive approach to stunt driving, car chases, and multi-vehicle wipeouts is still being emulated today, albeit usually with the aid of computer graphics so as to spare the stuntmen of the 21st century from having to get whomped on the back of the head with skidding motorcycles. And in what might be the most telling point of all, Mad Max and its first sequel, The Road Warrior, inspired a feverish frenzy of plagiarism in Italy, lasting until the middle of the 1980’s— in those days, nothing said, “You’ve hit the big time now,” like having the Great Italian Rip-Off Machine take an interest in your work. Australian movies just didn’t get that kind of attention before 1979, nor (with a couple of exceptions) would they receive it again after the mid-1980’s, but for a few years there, Australian film was an export industry, in a way it never could have become on the strength of “serious” dramas alone.

In the vaguely defined but relatively near future, Australian society— and, we might safely conjecture, society most every place else as well— is tottering on the edge of total collapse. What’s worse, nobody really seems to understand why. The economy is in such desperate shambles that even vital government agencies are forced to operate out of buildings as dilapidated as any slumlord-owned tenement in Harlem, and the energy crisis has reached such dire proportions that auto manufacturers simply don’t bother to build performance-oriented cars anymore. The scarcity of both gasoline and powerful engines (combined, just possibly, with the certain knowledge that there’s a better-than-even chance that any given police cruiser is packing nothing more formidable than a turbo-charged slant-six) has perversely given rise to a counterculture of “glory-roaders,” lawless young thugs driving ostentatiously customized 20- and 30-year-old hot rods, and nomadic gangs roaming the countryside on similarly cranked-up Japanese motorcycles. Perhaps the most troubling symptom of societal decay, however, is the way in which the authorities seem to be keeping pace with their outlaw adversaries when it comes to violence, depravity, and wanton disregard for public safety. As we see when officers of the Main Force Patrol square off against a hot rod hooligan who calls himself the Night Rider (Vince Gil, from Body Melt and Stone), the main difference between a cop and a glory-roader is that the former has sirens and flashing lights on the roof of his superannuated and overworked Ford Falcon, and wears a little bronze badge on the breast of his black leather jacket to prove that he’s one of the good guys.

The Night Rider situation is a major embarrassment for the MFP. Rather than simply riding their bikes through town and terrorizing old ladies, the Night Rider and his girlfriend (Thirst’s Lulu Pinkus) have stolen an MFP Pursuit Special, an unmarked cruiser powered by one of the 5.7-liter V-8s usually reserved for the elite drivers of the Interceptor corps. As the Night Rider takes his stolen car on a rampage across both desolate countryside and populated territory, he attracts a veritable swarm of MFP pursuers, who between them manage to cause even more damage than the glory-roader they’re chasing. None of the regular cops have the horsepower to compete with a Pursuit Special, however, and it falls to Interceptor Max Rockatansky (an astonishingly young Mel Gibson) to run the Night Rider to ground. Due process of law is not the Main Force Patrol’s strong suit, and Rockatansky’s idea of apprehending the Night Rider is to force him to drive his stolen vehicle into the wrecked truck blocking the road ahead of him. If anyone notices that this has the undesirable side-effect of destroying the irreplaceable V-8 which he and his colleagues were so eager to recapture, nobody mentions it to Rockatansky.

It may be just another day in the life of a Main Force Patrol Interceptor, but that particular encounter is going to have grave repercussions not only for Rockatansky, but for practically everybody he cares about as well. The Night Rider wasn’t just a lone nut, you see. He was good buddies with a nomad biker called Toecutter (Hugh Keayes-Byrne, from Death Train and The Day After Halloween), and the gang which Toecutter leads essentially declares war on the MFP when word of the Night Rider’s death gets around. Toecutter and his minions turn out in force to meet the train carrying the remains of their comrade in arms (in a hilariously macabre touch, all that’s left of the Night Rider fits comfortably within a child-sized coffin), and then launch off on a major violence spree as if in celebration of his memory. They even make a point of chasing down a non-affiliated glory-roader who tries to sneak out of town with his girlfriend when things turn ugly. By the time Rockatansky and his partner, Jim Goose (Steve Bisley), arrive on the scene of the latter crime, the hot-rodder’s ‘59 Impala is nothing but a heap of chrome-bedecked scrap iron, his girlfriend is in a nearly catatonic state, and he himself gets picked up while fleeing, pantsless, from the site of his humiliation. Oddly enough, however, Toecutter’s newest recruit, the certifiably insane Johnny the Boy (Tim Burns), has been left behind for the Bronze to haul into custody. This may indeed be part of a deliberate attempt to frustrate the police, for much to the chagrin of everybody in the department, the MFP are forced to let Johnny go after Toecutter’s thugs intimidate all of the victims of and witnesses to their latest rampage into skipping out on the arraignment hearing.

It’s precisely that sort of thing that has Max Rockatansky just about ready to hand in his resignation. He knows better than anyone that he and his fellow cops are rapidly losing the battle against the rising tide of chaos, and he worries for his sanity every time he sees his comrades in action. MFP chief “Fifi” Macaffee (Roger Ward, of Turkey Shoot) knows he can’t afford to lose an officer of Max’s abilities, and he tries every trick he can think of to keep Rockatansky on the force. He appeals to his sense of pride; he spins endless cock-and-bull stories about “giving the people back their heroes;” he even surreptitiously orders the MFP’s head mechanic to modify the last V-8-powered car to be added to the motor pool into a 600hp, nitro-burning monster, and hints that this awesome machine will become Max’s primary ride if he’ll agree to stick around. But when Toecutter and Johnny the Boy lead Jim Goose into an ambush and burn him alive in an overturned pickup truck, Rockatansky tells Macaffee that he’s had enough, and he really means it this time. The best Fifi can do is to give Max a few weeks off to take his wife (Joanne Samuel) and child (Brendan Heath) on a vacation in the country, with the understanding that he’ll use the downtime to reconsider his decision to resign.

As it happens, Max does indeed change his mind, but not for any of the reasons Fifi had envisioned. He takes his family to stay with a relative (an aunt, maybe?) named May Swaisey (Sheila Florance) and her halfwit son, Benno (Max Fairchild, from The Blood of Heroes and Howling III: The Marsupials). One day, while Jessie Rockatansky is out shopping, she encounters Toecutter’s gang, and just barely escapes with her life. The bikers track her back to May’s ranch, where they lie in wait for a chance to resolve their unfinished business with her. After artfully diverting Max and Benno, Toecutter and his boys make their move; by they time they’re finished, Jessie is in a coma from which she is unlikely ever to emerge and Baby Sprog is roadkill with diapers. Max, who had so recently lamented to Fifi that life on the highways was steadily turning him into a “terminal crazy,” now embraces a level of madness that might give even his contentedly deranged fellow cops pause. He returns to work, climbs into his tricked-out new Interceptor, and hounds Toecutter’s gang to total destruction like an angel of vengeance with a Weiand supercharger in place of the traditional flaming sword.

The conventional explanation has it that Mad Max was such a big hit in the United States (and, to a lesser extent, in other export markets as well) because of its close kinship with the Western. Certainly there is much to be said for this interpretation. Toecutter and his gang could stand in equally well for a band of outlaw gunslingers or for a tribe of marauding Indians, and Max himself is— at least initially— well within the tradition of the mythic lawman. But at the same time, there’s another, possibly more fruitful way to look at Mad Max’s Stateside success. The US, like Australia, is a huge country which is held together by its highways more than anything else. As with Australia, America’s population density is greatest along its coasts, there are huge swaths of desolate land in the interior which are virtually uninhabited, and unless you live within the city limits of a major metropolitan center, there’s simply no way in hell you’re going to be able to make it without an automobile for any length of time. And not coincidentally, people in the United States are, in aggregate, every bit as car-crazy as the Australians. NASCAR, dragstrips, monster trucks, funny cars, hot-rodders, lowriders, the Indianapolis 500— what it all adds up to is that there is a sizable fraction of the American people for whom “torque” and “horsepower” might as well be the names of minor pagan deities, and on whom a phrase like “the last of the V-8 Interceptors” is going to exert an irrationally powerful emotional tug. American audiences responded just as strongly as those in George Miller’s home country to the personified, fetishistic— indeed, nearly erotic— way in which Mad Max presents its motor vehicles. When we see Toecutter and his boys tear the other glory-roader’s Impala to shreds, we understand that we’re not just looking at an act of vandalism— in the terms of the exaggerated car-culture of Mad Max, we’re looking at a rape. (While we’re on the subject, notice that the literal rape of the glory-roader’s girlfriend— and apparently of the glory-roader himself— happens off-camera, in such a way as to imply that the destruction of the car is the real violation.) We also instantly latch onto the symbolism of that black, unmarked Interceptor; by the time Max starts driving it, he is an officer of the Main Force Patrol in name only— his personal vendetta requires an equally personalized vehicle to serve as his instrument of vengeance.

That last point brings us to a feature of Mad Max that makes it strikingly different not only from the great majority of the action movies that preceded it, but indeed even from its own sequels. For both the glory-roaders and the Main Force Patrol, their vehicles aren’t just the main means of getting around and a convenient way to externalize their personalities; they’re also the weapon of choice in most situations. The preference which this film’s characters exhibit toward killing with their cars and motorcycles instead of their guns is every bit as noticeable and extreme as the oft-remarked-upon bias against firearms on display in the slasher movies of the 1980’s. Lots of people carry guns in Mad Max, but only rarely does anybody shoot one off, and almost never directly at another person. Rather, the standard form of attack is to run one’s opponent off the road, preferably at maximum speed and into some sort of roadside hazard. Alternately, a pedestrian might be flattened outright or dragged to death behind a speeding motorbike, and between the deadliest of adversaries, nothing short of a gas-tank cookout will do. Somehow this has the paradoxical effect of increasing the impact of the violence even as it depersonalizes it— it’s as if the transgression is made all the worse for having been committed with something that was not designed to be a weapon.

What interests me the most about Mad Max, though, is that it doesn’t quite fit into the pigeonhole which it did so much to create. Between them, this movie and its first sequel laid the ground rules for the 80’s post-apocalypse film, yet in Mad Max at least, the apocalypse has yet to arrive. This first time around, George Miller presents us not with the pathetic remnant of humanity squabbling over the corpse of Western civilization, but with a snapshot of that civilization just a few years prior to its death throes. For all the horrendous dysfunctionality of such institutions as the police force and the court system, those institutions do still exist, and are still trying gamely to perform their functions. People still have regular, paying jobs from which they periodically take vacations, which they still do by loading up the camper van or RV trailer and heading off to the country to stay for a week or two with their aunties. Mothers still go shopping at the market, children still cajole them into buying ice cream cones, mechanics still try to talk customers into paying for unnecessary repairs, and even the glory-roaders are as yet looked at as just one more frightening and incomprehensible youth subculture, not so much different from the greasers, hippies, bikers, and punk rockers who preceded them. As such, Mad Max is not really post-apocalyptic but pre-apocalyptic; there has been no discrete calamity— no nuclear war, no pandemic plague, no world-wrecking environmental catastrophe— but rather a world slowly and insidiously laid low by the Second Law of Thermodynamics. There’s nothing wrong with civilization but an extremely advanced case of entropy, but despite that, the dominant impression this movie leaves is that it will be an enormous mercy when the total collapse which is now faintly visible on the horizon finally gets here. The world of Mad Max is one which is longing to be put out of its misery.

Yes, you say, but is the movie any good? Oh yes, although it has its weaknesses, many of which were exacerbated by the unnecessary dubbing in the American version. Despite all the foregoing, Mad Max is not a very thoughtful movie, and Miller and his colleagues spend little time on exposition— even on exposition that bears directly on the central plot. Far more is implied than ever gets developed in detail, and the characters (including Max Rockatansky himself) are treated more as archetypes than as living people. The handling of characterization is rather curious, for apart from Jessie the Generic Young Mother, the folks who populate this story are a highly eccentric lot, less true archetypes than their Bizarro World doubles. The cops are, for all practical purposes, a government-sanctioned gang. The chief of police— the one who spouts off constantly about giving people back their heroes— looks like the bouncer at a gay bar. (In the US theatrical prints, which had the dialogue track overdubbed on the theory that all those Aussie accents would be bad for business, Fifi Macaffee’s cartoonishly gruff new voice makes him seem like even more of a leather daddy.) Max’s character arc is not a rise into heroism but a descent into sociopathy. But by handling these skewed and twisted figures as if they were familiar stock types, Miller creates a more compelling film than he might have either by going the purely traditional route or by directly addressing how far from the norm most of the characters really are, while simultaneously taking it easy on a cast with only limited acting experience. In essence, Mad Max uses cognitive dissonance to its advantage.

It also massages the adrenal glands like few movies before had even attempted. Because there was so little money available to pay for professionals, a considerable fraction of the stunt drivers used in Mad Max were volunteers, and a considerable fraction of those were real outlaw bikers. What the volunteers lacked in technical proficiency they more than made up in risk-taking, and the chases and crashes in which they participated have an edge of wild earnestness about them that has seldom been matched. The effect is further magnified by the way in which the driving scenes were filmed. Mad Max was the first car-wreck movie to make such extensive use of cameras mounted directly in and onto the vehicles, and it put audiences in the thick of the action to an unprecedented degree. Watching one of this movie’s set-pieces is like being one of the unfortunate bystanders who so frequently get caught in the middle when the Bronze and the glory-roaders square off against each other, and it is here that the influence of Mad Max upon subsequent action films is most evident. Other filmmakers were quick to absorb the lesson which Miller was teaching, and the techniques which he pioneered here would be the standard of the industry for the next twenty years. What’s more, even the biggest departure of recent years— the widespread use of computer graphics to enhance or create stunts that would be simply too suicidally dangerous to undertake in the real world— is really just an attempt to go further in the same direction, although I personally don’t feel that it has been a terribly successful one to date. This is one instance in which the Aussies can legitimately claim to have shown the rest of the world how it’s done.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact