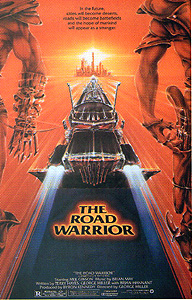

The Road Warrior/Mad Max 2/Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (1981/1982) ****½

The Road Warrior/Mad Max 2/Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (1981/1982) ****½

Of all the many nations that have developed an indigenous exploitation movie industry since the 1890’s, Australia is nearly unique in having one specific film that defines that industry in the eyes of most everyone who knows of its existence. Other products of the Aussie grindhouse have achieved some level of fame overseas, but The Road Warrior really is in a class all its own. More than just one of the elite handful of sequels that improve upon their predecessors, The Road Warrior is a sequel that fulfills its predecessor’s promise. Mad Max heralded the emergence of what has lately been dubbed “Ozsploitation” as a phenomenon of international significance, but The Road Warrior marked the emergence itself. It instantly became the proximate inspiration for a worldwide rip-off industry, its influence so lasting that riffs on its premise and iconography would still appear sporadically fifteen years later even despite the strip-mining it received from the Italians in the immediate aftermath of its release. And to a greater extent than even Mad Max, The Road Warrior still manages to thrill, effortlessly surpassing all but the best of the increasingly adrenalin-addled action movies that have appeared since.

The Road Warrior picks up from its predecessor in an unexpected way, by filling us in on some of the back story that we were denied except by implication in Mad Max. It turns out there had been a third world war after all, but one that was waged without recourse to the vast nuclear arsenals that had been stockpiled since 1945. This war caused a terrible drain on the world’s resources, so that it was an impoverished and exhausted planet that greeted its eventual end. We saw how that exhaustion affected Australia the last time around, and the decay has only accelerated since then. By now, an unknown number of years after Max Rockatansky (Mel Gibson again) gave up enforcing the law for the sake of bloody personal vengeance, civilization has disappeared from the island continent altogether. The nomad bikers and glory roaders have evolved into roving armies of scavenging savages, living precariously off of plunder and salvage. The exigencies of this lifestyle are such that there is no commodity the nomads prize more highly than gasoline, and that’s about where we stand when we are reintroduced to Max in the midst of a running battle against members of one such gang, on a highway somewhere in the desert of New South Wales.

Max still has the formidable Falcon XB GT interceptor he stole from the Main Force Patrol motor pool way back when, although he’s subjected it to a great deal of further customization in the intervening years. What he does not have is more than a few liters of fuel in his tanks, and the nomads chasing him are pretty well equipped themselves. Nevertheless, some clever tactics involving the wrecks of a huge tractor trailer and several lesser vehicles enable Max to winnow the forces arrayed against him to just their leader (Vernon Wells, of Fortress and Circuitry Man) and the much younger and much prettier leatherboy (Jimmy Brown) he has riding double on his bike. The last two marauders withdraw, leaving Max to replenish his fuel supply from the vehicles of his slain enemies. The rig and its associated junkers, on the other hand, have been picked over too thoroughly to offer anything of much value.

A while later, Max comes upon something much stranger than the derelict truck, a one-man autogyro that looks like it’s still in flying condition. While Max investigates (demonstrating his lightning-fast reflexes by snatching a venomous snake from its perch on the gyrocopter’s rotor shaft), he is ambushed by a crossbow-wielding man (Bruce Spence, from Cars that Eat People and Queen of the Damned) who had hidden himself beneath a patch of loose sand nearby. The gyro’s owner means to divest Max of his gas, but that won’t be quite as simple as he thinks. As Max smugly warns, his gas tanks are booby-trapped with a bomb, and anyone who doesn’t know how to disarm it isn’t going to like what they get should they attempt to siphon the fuel. Max also has a dog in the car with him, and while it’s neither especially big nor especially fierce, it’s enough to distract the pilot sufficiently for Max to gain the upper hand. The pilot still has one card to play in preserving his life, though. He knows of a settlement about twenty miles away, built around a functioning oil well and refinery. The place is fortified and heavily defended, but if anybody were going to figure out how to get inside, Max would be the one. And if he kills the pilot, he could spend years combing the desert without ever stumbling upon it. Max concedes that such information would be well worth sparing the pilot’s life.

Now, implicit in “fortified and heavily defended” is the notion that one does not just drive up and knock on the front door. As if to underscore the obviousness of that premise, Max and the pilot find the refinery settlement under siege from a horde of highway pirates when they reach the ridge overlooking the village. And whom should Max spy among the besiegers but the head of the gang he tangled with earlier? Conditions down on the plain suggest that the biker with the two-tone mohawk (we’ll discover later that his name is Wez) is merely the number-two man in this army, which has numbers, horsepower, and weaponry beyond Toecutter’s wildest dreams. The siege is in a state of stalemate (as sieges tend to be for most of their durations), but shortly after dawn on the second day of Max’s observations, the settlers launch an attempt at a breakout. Three vehicles charge off toward the southwest, pursued by nearly half of the besieging horde, while a fourth takes the opposite bearing, trailed by a much less powerful intercept force, the latter led once again by Wez. When it becomes clear that Wez and his men are going to catch their prey, Max thinks he sees a chance to ingratiate himself to the villagers. Although self-preservation demands that he not attempt a rescue until most of the brigands attacking the blockade runners return to the siege line, making him too late to save the woman driving the buggy from being raped and murdered, her male companion is still alive (albeit badly wounded) when Max arrives on the scene. He quickly overpowers the one warrior left behind to guard the captured vehicle and its cargo of provisions, then strikes a deal with the injured settler— Nathan (David Downer) is his name, by the way— according to which Max will receive as much gasoline as he can carry in exchange for ferrying Nathan back to the refinery.

The reception that greets Max when he sneaks through the pirates’ perimeter during a lull in the fighting is mixed, to say the least. Some of the settlers— one whom I take to be Nathan’s mother (Moira Claux), the girl who evidently handles most of the colony’s medical duties (Razorback’s Arkie Whiteley), the old man who appears to be the medic’s father (Syd Heylen)— are too busy worrying over Nathan to take much notice of the man who brought him home. Others, like the crippled mechanic (Steve J. Spears) or the woman who is arguably the refiners’ deadliest fighter (Virginia Hey), are openly hostile, and would like to toss Max out on his ass at once, appropriating his interceptor for the colony’s use. Pappagallo the leader (Mike Preston, from Metalstorm: The Destruction of Jared-Syn) mainly wants to know who Max is, how he made it through the nomads’ cordon, and what he knows about the fate of the seven scouts he didn’t have packed into his car. Max explains about the fuel-for-rescue bargain he made with Nathan, but when Nathan dies of his injuries, Pappagallo bluntly says that whatever arrangement they had died with him. Consequently, it’s rather a stroke of good fortune for Max when the barbarians renew their attack, giving his increasingly unwilling hosts something much more pressing to deal with.

Like I said, this lot makes Toecutter and his boys look like a bunch of pussies. Their chief (Kjell Nilsson) calls himself the Lord Humungus, and the name is more than apt. Imagine Jason Voorhees (complete with goalie’s mask) as the head of security at a gay bondage dungeon, and you’ll have the general idea. The Lord Humungus has a pretty deft touch with psychological warfare, too, delivering threatening speeches over the PA system built into his nitro-burning 6x6 while his minions skirmish along the compound walls. This time, he’s got something really good to hold over the settlers’ heads. His men took four of the eight blockade runners alive (they’re all tied to the front ends of the gang’s larger vehicles to substantiate the claim), and the Humungus now knows what their mission had been: to find a truck big enough to haul away the tanker trailer in which the villagers have been storing the gasoline they make, enabling them to pull up the stakes and escape from the Outback to someplace less hospitable to roving motorized raiders. Well, if the settlers want to leave so badly, that’s fine with the Humungus— so long as he winds up with their fuel and their refinery. Surrender now, he offers, and he will spare all their lives and guarantee them safe passage through the territory he controls. He gives them 24 hours to decide, then withdraws his army to the hills.

Here, then, are the considerations before the settlers: 1. The slow but steady attrition from the bandits’ raids has placed a clear limit on how long they can continue to hold the refinery, so abandonment of their colony is unavoidable one way or the other. 2. Accepting the Humungus’s terms would mean giving up their most valuable portable resource, leaving them without the basis on which they had planned to rebuild once they settled down again, but they are in no credible position to move the tanker as things stand. Quite a few of the colonists argue that giving the warlord what he wants while he’s still in the mood to grant them anything in return is therefore their only realistic chance of escaping with their lives. On the other hand, most of those who have been doing the fighting point out that they’d be placing themselves at the mercy of a man who has demonstrated time and again that he has none. Also, although no one within the walls has any way of grasping the true significance of this event, the last visit from the Humungus sparked a skirmish between some of his soldiers and a strange, feral child (Emil Minty) whom the settlers had taken in. Wez’s boyfriend was killed during the altercation (never fuck with a cave-kid who carries a sharpened steel boomerang), and the Humungus has promised his lieutenant a chance to exact his vengeance once the refinery is safely in their hands. I believe we can predict exactly how safe that “safe passage through the wasteland” is going to be, don’t you? Once again, though, the colonists’ misfortune is Max’s opportunity. They need a rig that will haul their tanker? Well, that truck he passed by two days ago should do nicely if he can get it running, and it looked like most of the damage it had suffered was confined to the trailer. With the aid of the autogyro pilot (who was still manacled to a substantial uprooted tree stump when Max left him, and who would no doubt be happy to perform another favor in return for the keys to his shackles), Max thinks he can deliver the rig to Pappagallo’s people before sunset tomorrow. The price he quotes seems quite reasonable, too, all things considered— they give him back his interceptor with the tanks topped off, together with all the spare gas he can carry. Pappagallo assents to Max’s bargain, and now all the Road Warrior has to do is make it through the Humungus’s blockade alive. Twice.

It’s amazing how little The Road Warrior suffers from the overfamiliarity generated by the likes of Steel Dawn and 2020 Texas Gladiators. Its plot of cinematic territory was plowed over subsequently by every bunch of nitwits with a movie camera, a fast car, and access to a little-used stretch of desert highway, but The Road Warrior is every bit as compelling today as it would be if none of those other post-apocalyptic crypto-Spaghetti Westerns had ever happened. What’s really strange is that this should be so even though writer/director George Miller and his co-scripters, Brian Hannant and Terry Hayes, followed precisely the template that can normally be counted upon to produce the very worst, most imbecilic sequels. They basically just made a movie that was more of whatever Mad Max had been. The Road Warrior has bigger and more complex action set-pieces, a faster pace, an even weirder cast of characters operating within a setting of even greater dysfunction and hostility, and stunts that have raced on past the merely dangerous into the country of the nearly insane. I think the reason it works here despite its near-perfect record of failure otherwise is because it dovetails so neatly with the movie’s premise. Mad Max was about a man fighting a losing battle against entropy in a society doing the same on a larger scale. The Road Warrior shows what happens after entropy has triumphed, both in Max’s life and in the world he inhabits. It stands to reason that all of the things that served in the first film as signs and symptoms of social and psychological disintegration— the violence, the disregard for human life and safety, the personal freakishness of nearly everyone who passed in front of the camera— should take on monstrously exaggerated forms now that the forces of chaos and decay have completely slipped their leashes. Of course, it also doesn’t hurt that Miller has had two more years in which to think about how to do this sort of thing, or that the astonishing profitability of Mad Max made the sequel look like a safe enough bet to justify a nearly tenfold budget increase. Miller had plenty of time to figure out what he was going to do for an encore, and he didn’t have to cut any corners in making it happen.

Another point in The Road Warrior’s favor is its astute expansion of its predecessor’s already exceptionally credible fictional world. World War III had figured in virtually every apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic sci-fi movie since the mid-1950’s, but The Road Warrior is the first such film I can think of to contemplate a purely conventional future world war, just as Mad Max was the first in my experience to envision a slow and gradual end to civilization. It should be obvious, too, that an intense, prolonged, and widespread bombs-and-bullets conflict would be the surest way to set in motion the lingering apocalypse by exhaustion that Miller and Byron Kennedy had already posited. The gradual nature of the world’s end is also the key factor underlying the visual style of The Road Warrior, which permanently codified the production design esthetic that I like to call “garbage tech.” Later movies adopted it basically because it looked cool, but here, it’s a logically consistent outcome of the initial premise. No nuclear exchange or global geological catastrophe means no irreparable wholesale physical destruction, so all the products of modern civilization remain available to be scavenged and repurposed— albeit in steadily dwindling quantity, as the struggle for basic survival increasingly supercedes all other considerations. This paradoxical combination of plentitude and scarcity can be seen most readily in the arms and armor used by both the Humungus’s army and the defenders of the refinery. Firearms, in essence, have become luxury weapons, desirable for their great lethality but impractical due to the difficulty of obtaining appropriate ammunition. Some aluminum doweling, some heavy-duty tin-snips, and a steel file, and you’ve got yourself the ingredients for a quiver-full of crude but serviceable arrows; making .44 caliber magnum loads, on the other hand, requires specialized knowledge, tools, and materials. Among the raiders, only the Humungus himself carries a gun, and with just five bullets to his name, he has to be very careful about when and how he uses it. Apart from the central importance of motor vehicles, combat in The Road Warrior consequently has a decidedly medieval character, with crossbows, melee weapons, and improvised firebombs pitted against suits of armor scraped together from biker leathers, sports equipment, and random scraps of quilted padding. Pappagallo’s people show similar ingenuity in the design and construction of their compound, especially in the armored school bus that serves as the main gate and the ungainly contraption (apparently made out of an engine block hoist and a squadron of bicycles) that enables the paraplegic mechanic to get around and render his vital services to the colony. Under the circumstances put forward here and in Mad Max, this is exactly what you’d expect life after the end of the world to look like.

There’s one last thing I want to mention about The Road Warrior, a striking bit of characterization that might be taken to apply the “like Mad Max, only more so” principle to an element of the first movie’s subtext. A lot of commentators have interpreted Toecutter’s gang as a marauding band of homosexuals, mainly because they wear a lot of leather, because they have no women in their orbit apart from the Night Rider’s girlfriend, and because Toecutter blows up a female mannequin with a shotgun when he gets tired of watching his men amuse themselves by molesting it. I’ve never really bought that myself, although I can certainly see the reasoning behind it— I’ve just known way too many leather-clad straight boys who regarded females as an inscrutable and occasionally terrifying alien lifeform over the years to settle for such indirect implications. But Wez carting the blond guy around on the back of his motorcycle, fastened to his belt with a chain and a padlocked dog collar? Having the Lord Humungus tell Wez, “I understand your pain— we’ve all lost someone we love,” while holding him back from charging in to wreak immediate revenge after the blond guy’s slaying? Now that’s the kind of implication I’ll buy. The really interesting thing is that, assless leather pants notwithstanding, Wez is not the slightest bit stereotypically faggy. He is far and away the toughest, bravest, fiercest, and most all-around capable warrior the Humungus has in his employ, and to a greater extent even than the Humungus himself, Wez is Max’s nemesis in this adventure. I can’t think of any other movie from the early 1980’s— hell, I’m not sure I can think of one today— that features a more or less obviously gay villain who is nevertheless defined more by his villainy than by his gayness, and whose gayness is not presented specifically as part of what makes him a villain. I’m sure if I looked hard enough, I could still find some grumbling essay by one or another of the Role Model Police, condemning The Road Warrior for portraying homosexuals as aberrant, sadistic sociopaths, but you know what? Fuck those whiners. Good or evil, I say it’s time we had some more totally bad-ass queers around here, and anybody who wants to try writing such a character could learn a lot from Wez.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact