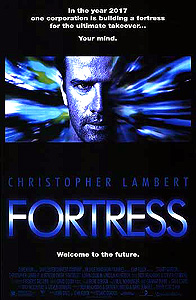

Fortress (1993) ***Ĺ

Fortress (1993) ***Ĺ

If thereís any genre that fared worse in the 1990ís than low-budget horror, itís dystopian sci-fi. The Italians had bled the Road Warrior formula white in the preceding decade, while American dystopia came to be defined increasingly by the films of Albert Pyunó and Cyborg was as good as those ever got! If I see one more movie that sticks a third- or fourth-string action hero in an abandoned steel mill or an Arizona junkyard, and then tries to convince me Iím looking at somebodyís nightmare vision of an all-too-possible future, Iím going to Fedex the producers a large jug of my own urine. So Iím sure you can imagine why I was leery going into Fortress, an early-90ís US-Australian co-production that stars Christopher Lambert as a man unjustly confined to a brutal, futuristic prison. I mean, does that sound like the recipe for agony, or what? What I had failed to take into consideration in that analysis was director Stuart Gordon. Gordon could make a good movie even with Charles Band looking over his shoulder, and Fortress, though often looked down upon, is much better than we have any right to expect from a film of its type.

The first smart move Gordon makes is to forego the usual opening crawl or voiceover exposition. He just drops us into the movie and leaves us to fend for ourselves. Our heroes are a married couple named John and Karen Brennick (Christopher Lambert, of Highlander and Beowulf, and Loryn Locklin from Night Visions), who are currently waiting in a long line of cars at the American border. Evidently the world of Fortress is one in which The Population Bomb proved a rather more accurate prediction of future trends than was the case in ours, because the totalitarian government that now controls the US has laid down rigid laws limiting the number of children a household is permitted. Wherever it is that the Brennicks had gone, they presumably did some serious fucking while they were abroad, because Karen is now illegally pregnant, and therefore not allowed to reenter the country. Her husband is a captain in the army, though, and the Brennicks hope that by wearing Johnís flak jacket under her coat, Karen will be able to sneak past the sonic scanners that are an invariable part of the customs inspection at the border. They very nearly make it through, but then one of the border guards notices the gleam of Johnís brass rank insignia poking out above Karenís collar, and the couple are busted. John attempts to save his wife by drawing the maximum possible attention from the guards, but itís really no use.

The next we see of Brennick, heís on his way to the Fortress, an underground supermax detention facility located deep in the most inhospitable section of the Southwestern desert. (Actually, itís Australiaó evidently the American producers didnít think their own deserts were picturesquely awful enough.) We donít hear just how long John has been sent up for, but it seems a safe bet that itís going to be a fucking long time. The Fortress has all the amenities one expects from a sci-fi movie prison. The cells are closed off not by bars, but by flesh-vaporizing laser beams. Inmates are watched 24 hours a day by roving computerized security cameras mounted on tracks in the ceiling. And the prisoners are, of course, kept in line with electronic pain-inducement devices that turn lethal in the event of an escape attempt. (Kudos to the filmmakers, however, for coming up with something other than the usual exploding collars. Instead of that hoary commonplace, Fortress uses gizmos called ďintestinators,Ē which are implanted in each prisonerís gut upon arrival at the prison.) There are other wrinkles to the security regime in the Fortress that we havenít seen before, however. The prison is patrolled by heavily armed cyborg soldiers, and all the exits are covered by computer controlled particle beam turrets whose rays destroy organic matter while leaving the steel and concrete of the surrounding structure unharmed. Furthermore, from his control room in the very core of the prison, Fortress commandant Poe (Kurtwood Smith, from RoboCop and Boxing Helena) can keep tabs not just on his prisonersí movements, but even on their dreamsó main computer Zed-10 (voiced by Carolyn Purdy-Gordon, of Re-Animator and Robot Jox) is able to read the inmatesí brainwaves, and alert Poe whenever one of them is dreaming of a prohibited subject like sex or escape. But as always, the prison authorities are only the beginning of a new inmateís troubles.

Like most US prisons even today, the Fortress suffers from massive overcrowding, and John winds up sharing his tiny, two-bunk cell with four other men. One of these, Nino Gomez (Witch Huntís Clifton Gonzalez Gonzalez), is a new jack like himself. The other three have been in for a long time, and look likely to be staying in for a longer time still. Abraham (Lincoln Kilpatrick, from Soylent Green and The Omega Man) could very well be the least troublesome man in the entire facility; heís a trustee prisoner with a parole hearing coming up, and he doesnít want to do anything to get on Poeís bad side. The only trouble techno-wizard D-Day (Jeffrey Combs, of The Pit and the Pendulum and The Phantom Empire) is likely to make is directed at his overseers. But Stiggs (Tom Towles, from Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer and House of 1000 Corpses) is a different story. Stiggs is tight with Maddox (Vernon Wells, from The Road Warrior and Space Truckers), the psycho hard-ass par excellence of the Fortress, and together with Maddox, he considers himself to have presumptive rights to the rear ends of attractive young new guys like Nino. Brennick begs to differ. In fact, not only does he face down Stiggs in their cell, when he sees Maddox trying to rape Gomez on work detail a day or two later (all the male prisoners spend their days laboring to enlarge the Fortress to accommodate the steady inflow of new inmates), Brennick steps in again to protect his cellmate. The resulting fight earns everyone involved an intestination, after which Maddox, Brennick, and Gomez are put in solitary confinement until one of them gives in and rats out the man who started the fight. Brennick confesses when Nino starts to crack; he figures the boy can count on enough trouble from Maddox as it is.

The false confession gets Brennick his first meeting with Poe, who supplies him with the information that his wife is also confined in the Fortress, in the uppermost section reserved for illegally pregnant women. Abortion being also proscribed by law, the contraband babies are brought to term, after which they officially become the property of the Mentel corporation, which owns and operates the Fortress. (Note that the privatization of the US corrections industry was only just beginning in 1993, when this movie was made.) The commandeered infants are then converted into cyborgs like the Fortress guards and even Poe himself. Poe tells Brennick all this in the hope that it will make him more controllable if he knows Karen is imprisoned with himó the implication being that anything could happen to Karen if John ever pushes the commandant too far. But in point of fact, it ends up working the other way around, with Poe using Johnís fate to extort concessions from Karen. Maddox seeks Brennick out as soon as he is returned to the regular section of the prison, and the rematch between the two men ends with Maddox being gunned down by a particle beam emplacement while a thousand or more prisoners chant Johnís name in a manner that Poe finds most disturbing. Looking to head off a potential revolt before it starts, the commandant subjects Brennick to the dreaded Mindwipe procedure, sending him back to his cell several days later as little more than a human vegetable. Heíd have had it even worse, too, had Poe not realized the enormous blackmail potential of the situation. Poe brought Karen Brennick down to his office to witness her husbandís ordeal, and told her that it would end if she agreed to accept trustee status herself, becoming in effect Poeís concubine. Karen, however, seems to have relented too late to save her husbandís mind.

Or did she? After getting Poe drunk one night (cyborgs evidently canít hold their liquor), Karen sneaks into the Fortress control center, and uses the brainscan capabilities of Zed-10ís roving cameras to draw her husband out of his catatonia. Meanwhile, she begins working on Abraham, trying to make him see that his diligent ass-kissing is an exercise in futilityó Poe will vote against his parole no matter how well Abraham behaves. Then, back in his cell, Brennick gives D-Day the intestinator he snagged from what was left of Maddox after their brawl, with instructions to figure out how it works and how the ones still inside the rest of them might be deactivated. D-Day does better than that; he discovers a way to use the devicesí natural magnetism to remove them from the menís bodies altogether, leaving Brennick and his cellmates (even Stiggs) free to use the intestinatorsí destructive properties to aid in an audacious escape attempt.

My favorite thing about Fortress is that its dystopian sci-fi elements are really just window dressing. Rather than being yet another Road Warrior, Blade Runner, or 1984 rip-off, Fortress is instead a prison movie in the classical style at heart. The intestinators and cyborg guards and dream-peeping computers are merely props that give Stuart Gordon a fresh way to retell a story that is as old as the modern penitentiary system. In John Brennick, we have the quietly unbreakable man who is gradually forced by the evil of his keepers to step beyond his stoicism and take up arms against the corrupt authorities. Nino and Abraham give us the characters who rise above their weakness and complacency to become indispensable allies to the hero. And in Stiggs, we see the thug who is inspired to redeem himself by the heroís courage in the face impossible odds. All are not so much cliches as archetypes, and itís difficult to imagine an action-oriented prison story without them. And because archetypes speak for themselves, it doesnít much matter that Christopher Lambert, Clifton Gonzalez, Lincoln Kilpatrick, and Tom Towles are actors of limited ability. Even archetypes get old, however, and the shift into sci-fi territory does much to revitalize the ones employed here. The futuristic setting also helps by creating opportunities to work in story elements that would require painfully obvious contrivances if Fortress had been set in the present day. The most obvious of these is the role that Karen Brennick plays in the story; in a present-day prison, where total gender segregation is the norm, this important plot thread simply wouldnít be possible except via the most egregious cheating. This way, the Evil Warden gets to have something unusually awful to hold over the head of our hero, and the story doesnít have to twist itself into pretzels for him to do so. The Mindwipe machine is another example of how the filmmakers use the sci-fi trappings to breathe new life into a cliche. In Fortress, it serves the same dramatic function as the stint in the hole or the trip to the torture dungeon would in a conventional prison flick, but it serves that function in a way I havenít seen before. Iíve always been a sucker for movies/books/TV shows/whatevers that find a new and interesting way to tell a well-worn story, and tell it well. And despite its inauspicious appearance, Fortress is most assuredly that.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact