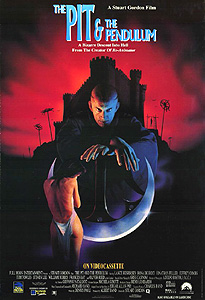

The Pit and the Pendulum/The Inquisitor (1990) ***½

The Pit and the Pendulum/The Inquisitor (1990) ***½

Back in the 80’s, when there was still a theatrical market for cheaply made movies, Charles Band produced a handful of decent films, and even one brilliant one. His track record in the direct-to-video market has not been so good, however. For the most part, I steer well clear of anything bearing the imprints of Full Moon Video, Torchlight Entertainment, and their sister labels, having long ago learned that those outfits have little if anything to offer me. There was a brief period during the early 90’s, though, when that little Full Moon logo was not necessarily synonymous with depressingly amateurish crap. In those days, Charles Band still had a bit of money to throw around, and his company’s financial situation was not yet tailor-made for driving anyone with the slightest modicum of talent out of the Full Moon fold. In the early 90’s, Full Moon even had a distribution deal with Paramount, and Band’s movies were likely to find a wide enough audience that they could still make a healthy profit without having to pare back their budgets to AIP-TV levels. It was during this lamentably short period that the studio which would eventually transform itself into little more than a factory for cranking out ever-cheaper Puppet Master sequels released what must surely be the crown jewel of its catalogue: Stuart Gordon’s The Pit and the Pendulum.

I’ve talked before, in the context of AIP’s Poe movies from the 60’s, about the obstacles confronting any filmmaker who decides to try his hand at bringing Poe to the screen. In my copy of The Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe, “The Pit and the Pendulum” takes up a mere eight pages. It might manage twelve in a mass-market paperback edition with larger print and wider margins. The action is confined to two settings, can be divided into all of three scenes, and concerns only one character who does anything more than read a death-sentence off of a piece of parchment. Film what Poe wrote, and you’ve got maybe ten minutes of screentime— ten boring minutes, too, when you take into consideration the fact that those eight pages worth of story unfold over the course of several days, and that the titular pendulum actually descends at a rate of perhaps two inches per hour. Roger Corman and Richard Matheson got around this obstacle by essentially grafting the pendulum vignette onto the end of a remake of their earlier The Fall of the House of Usher. Stuart Gordon and screenwriter Denis Paoli attack the problem in a rather more logical manner, leading up to the scene from which their movie takes its title with a plot that hearkens back to the wonderfully sleazy witch-burning movies of the late 60’s and early 70’s.

In Toledo, in the year 1492, the Grand Inquisitor Torquemada (Lance Henriksen, from Near Dark and Pumpkinhead— an actor no present-day Band production could possibly afford) leads a group of noblemen, soldiers, and Inquisition hangers-on into the crypt of a long-dead don, whom the Inquisition has belatedly concluded was in league with Satan. Professional thugs Gomez (Stephen Lee, of Black Scorpion and RoboCop 2) and Mendoza (Mark Margolis, from Tales from the Darkside: The Movie and Pi) open up the don’s sarcophagus, and Torquemada pronounces sentence upon the withered old corpse: the property of his house is to be confiscated and handed over to the church, while he himself is to receive twenty lashes. We are then treated to the amazing spectacle of Mendoza whipping the don’s dried-up body until it literally falls apart!

After a quick pause for the opening credits, the filmmakers introduce us to a debt-ridden baker named Antonio Alvarez (Jonathan Fuller) and his beautiful young wife, Maria (Rona De Ricci, in the last of her two measly screen appearances— if the Great Italian Rip-Off Machine hadn’t gone belly-up about five years back, this girl could have become a big deal in exploitation-movie circles). Maria is doing her damnedest to keep her husband’s mind off the bread he’s supposed to be baking (De Ricci can distract me from my job any time she wants...), and with understandable reasons— Antonio means to sell that bread at the auto de fé that afternoon, while Maria would best be described as a conscientious objector to those odious orgies of Church-sanctioned bloodshed, had anyone yet thought of the term in the late 15th century. Antonio’s businesslike mind is made up, though, and a few hours later, both he and his wife are out in the street, hawking their bread while holding their metaphorical noses at the moral ramifications of exploiting the suffering of the Inquisition’s victims in order to make a peseta. The couple’s idea is to sell all their loaves and then leave, getting home before the crowd moves off to the main square, where the auto de fé proper is to be held, but it doesn’t quite turn out that way. Complications stemming from the activities of a few shoplifting boys result in Antonio and Maria getting swept up in the crowd as it rushes through the narrow streets, and both of them thus wind up in the square when Torquemada takes the stand to oversee the burning of a “witch” (apparently the mummified don’s daughter) and the public flogging of her pre-teen son. Inquisition chancellor Francisco (Jeffrey Combs, from Re-Animator and Phantom Empire) reads the indictment, and the ghoulish spectacle begins. And because Maria just can’t seem to keep her big fucking mouth shut, she manages to get herself arrested on charges of witchcraft and Antonio clouted over the head and left for dead by Don Carlos, Torquemada’s captain of the guards (Tom Towles, of Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer and Tom Savini’s Night of the Living Dead remake).

This is just as bad as it sounds. Maria is taken before the Inquisition, at which point she is stripped and her body searched for “Satan’s mark” by Francisco, Don Carlos, and smirkingly lecherous Inquisition surgeon Dr. Huesos (William J. Norris, from Castle Freak and Campfire Tales). Once Don Carlos figures out that any sort of skin blemish could be considered a witch’s mark, he takes to pinching Maria savagely, passing off the welts he raises as the kind of marks the Inquisition seeks. But it isn’t until Torquemada himself examines Maria that the anvil really drops on her. The Grand Inquisitor, let us remember, has been a monk all his adult life. He has never once gotten laid, and now his line of work requires him to look over and handle the nude body of a radiantly beautiful girl— I believe Beavis and Butt-Head would have phrased it, “Boi-oi-oi-oi-oinnng!!!!” And you just know a sexually repressed, religious psychopath like Torquemada is going to take that hard-on as proof that Maria has cast a spell over him, don’t you? Sure enough, Maria is locked in a cell with a very real witch named Esmerelda (Frances Bay, from Arachnophobia and In the Mouth of Madness) just a few minutes later.

Meanwhile, Antonio has recovered from that blow to his head, and is doing his damnedest to get Maria released. When his initial attempt to appeal to Torquemada directly as a character witness on Maria’s behalf fails, Antonio bribes Gomez into sneaking him into the dungeon, so that he can break Maria free himself. But Gomez is a tricky bastard, and he leads Don Carlos and a squad of harquebusiers straight to Antonio the moment the latter man has found his wife’s cell. Torquemada’s intervention saves the Alvarezes from immediate death, but given the choice between being shot down by Don Carlos’s men and having my body gradually unmade by Mendoza and Gomez, I think I’d probably opt for the hail of bullets, myself.

Antonio, of course, is going to wind up under the titular pendulum before all is said and done, but standing between us and that scene is one of the most complicated plots ever to be put on the screen with Charles Band’s money. We’ll get to see a Conqueror Worm-like extortionate “romance” between Torquemada and Maria; a riff on Poe’s beloved catalepsy theme; a delightful, “Cask of Amontillado”-inspired subplot involving a cardinal (Oliver Reed, from Spasms and The Brood) sent by the Pope to reign in Torquemada’s excesses; an utterly unexpected side-trip through Richard III/Tower of London territory; and, of course, a whole lot of torture scenes cribbed from Mark of the Devil (albeit presented with none of that movie’s lecherous sadism). Not only that, there’s even a bit of the mordant humor Stuart Gordon displayed earlier in Re-Animator, courtesy of Gomez, Huesos, and (as is only fitting) Francisco.

But for me, what really makes The Pit and the Pendulum is Lance Henriksen. This is one of the very few times Henriksen has been cast in the part of a truly evil character, and he makes a terrific showing for himself. He certainly isn’t as smooth as Vincent Price would have been in the role (Henriksen’s performance would suggest the comparison even if this weren’t a semi-remake of one of Price’s best-known movies), and he seems to lack the confidence in his own overacting that would have been necessary for him to pull off some of his more outrageous scenes, but when the script lets him stick to “warped and obsessed” (as opposed to “flamboyantly diabolical”), he really shines. I can perfectly well imagine the historical Torquemada not having been that far removed from the character as Henriksen portrays him. (The real Torquemada was, of course, the father of the Spanish— as distinct from the Papal— Inquisition, and was by all accounts a right fucking bastard. And if ever you wanted to convince me that there is such a thing as Fate, you should start your case with him. “Torque” means “twist” or “hurt” in Latin, while “quemada” is Spanish for “burned”— that “a” at the end implying that the one being burned is a woman, specifically!)

There is one thing about this movie that bugs me, though. Oliver Reed’s character is supposed to be an emissary of the Pope, who has come to shut the Inquisition down. In the real world, not only was the Vatican 100% behind Torquemada, it had a bureaucratically separate Inquisition of its own which was every bit as brutal. The only meaningful difference between the two Inquisitions, as far as their victims needed to be concerned, was that Torquemada’s was organized in such a way that it was especially vulnerable to political corruption, and after Torquemada’s death, it rapidly evolved into something very much like a secret police agency for the Spanish crown, a sort of Renaissance Gestapo. Considering how honestly The Pit and the Pendulum deals with the Inquisition and its history in other respects (for example, Francisco’s explanation that only confessions under torture are acceptable— because a prisoner might otherwise confess falsely in order to avoid torture— really was the official position of the Church on the subject), this particular instance of “artistic license” stands out in a most annoying manner.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact