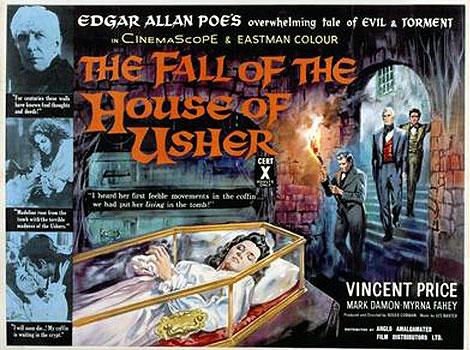

The Fall of the House of Usher / House of Usher (1960) ***½

The Fall of the House of Usher / House of Usher (1960) ***½

The Fall of the House of Usher/House of Usher was the first of seven (eight, if you want to count The Haunted Palace) films that Roger Corman directed for American International Pictures, based on the writings of Edgar Allan Poe. It’s not only one of the best entries in that loosely constituted series, but also easily the most faithful adaptation of any Poe story every to light up a movie screen. In addition, the film was a big success for the studio, and it is hardly a shock to see that AIP continued producing Poe movies long after Corman got sick of directing them.

The movie tells of Philip Winthrop (Mark Damon, from Black Sabbath and Crypt of the Living Dead) and his efforts to rescue his fiancee, Madeline Usher (Myrna Fahey), from the clutches of her mad brother, Roderick (Vincent Price). When Philip arrives at the fortress-like Usher mansion, he has at first no idea that Madeline is in need of rescue; he has merely come to enjoy his girlfriend’s company. The first sign of trouble comes when Bristol (Harry Ellerbe, of The Magnetic Monster and The Haunted Palace), the Ushers’ butler, refuses him entry into the house. The old man says his orders are to let no one in under any circumstances, especially if it’s Madeline they want to see. Apparently the girl is sick, and her brother has her under some kind of quarantine. But Philip Winthrop is not a man who takes no for an answer, least of all from a servant, and he bullies his way into the house anyway, finally winning an audience with Roderick. This is where the second sign of trouble comes in. Roderick calls his sanity into question the moment he opens his mouth. He insists that Winthrop talk at a level scarcely above a whisper, that he refrain from lighting candles or opening the curtains, and even that he remove his riding boots and go about the house in soft-soled slippers instead. The reason for all this rigmarole, or so Roderick claims, is that he has a rare congenital disease of the nerves that elevates his senses to superhuman heights of acuity. Stimuli of all but the lowest amplitudes are unendurable to him. Not only that, Roderick says that Madeline has the condition too, but that her case is not so advanced as his because of the significant difference in age between them. And if Roderick is to be believed, rare nervous disorders are only the beginning of his sister’s ailments, which she now has in such abundance that she is actually dying of them.

This comes as news to Philip, who found Madeline in quite good health the last time he saw her, some months ago when they were at college together. And considering that the girl herself appears in the room mere moments after her brother’s assertion that she is bed-ridden, Philip tends to think Roderick holds an exaggerated opinion of her condition. But strangely enough, Madeline seems to agree, for her part, with Roderick’s assessment of her health, and she refuses to leave the mansion and come away with Philip to be married. Worse yet, it seems that Roderick has convinced Madeline that she lives not just under the shadow of wasting illness, but under some sort of preternatural curse as well— something about evil and madness being inborn into the Usher lineage. Roderick has all manner of old family stories at his disposal to support his claims, enough tales of crime and craziness to fill an entire evening. But all Roderick’s yarns convince Philip only that his brother-in-law-to-be is a bad influence on Madeline.

His conviction that the girl must be removed from the old house posthaste is further intensified when Philip notices the huge crack in one of the mansion’s load-bearing walls, which stretches from below ground-level nearly to the roofline. It’s bad enough that Madeline should live with a morbid crazy man who wants her to believe that she is both terminally ill and accursed. Having her do so in a house that’s ready to come crumbling to the ground at any moment is simply ridiculous. But on the very night that Philip finally convinces Madeline to leave with him, the girl drops dead in the middle of an argument with her brother. Roderick’s hurry to get her interred in the family crypt initially seems less suspicious to Philip than the manner of her death, but the distraught young man changes his mind when Bristol tells him in some detail about the kinds of nervous disorders that run in the Usher family. If you have any familiarity at all with Poe’s writings, you’re going to see this coming a mile away: among other things, the Ushers tend to be cataleptic! Sure enough, Madeline claws her way out of the tomb a couple of nights later, and when she does, she’s more than a little annoyed with her dear old brother...

A lot of people are going to find The Fall of the House of Usher a bit slow for their taste. Richard Matheson’s script tends to wander, and most of the film’s running time is devoted to building up an oppressive atmosphere. Given that this is a Poe movie, however, I would contend that this quality is actually something of a selling point. Poe was all about atmosphere, to the extent that his stories often seem like disembodied climaxes set in great cobwebby masses of florid descriptive text. This has the effect of making his work very difficult to film, and it is thus understandable to some extent that few of the movies based on his writings are in any sense faithfully adapted. But with “The Fall of the House of Usher,” prospective filmmakers have a small advantage, in that it is among the most substantial of the author’s short stories, at least in terms of word count. Even so, the original tale has a miniscule cast of characters, and scarcely any real narrative at all. The whole point is to make the reader feel broody and stifled before hitting him over the head with the tomb-breaking, house-collapsing climax. So fans of Poe should be pleased to discover that that is how Corman and Matheson approached this movie as well, mounting a hard-hitting climax at the far end of 80 minutes of gloom and doom. On the other hand, the movie’s low budget is quite obvious, and the acting is a bit weak. Mark Damon’s performance is regrettably colorless, while Vincent Price breaks new ground by inventing a hitherto unimagined style of bad stagecraft: over-underacting— it’s really the sort of thing you just have to see for yourself. But even so, I think The Fall of the House of Usher is well enough written and well enough handled by its director to stand tall in the face of such shortcomings, fully rewarding those with the patience to see it through.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact