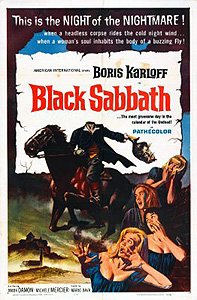

Black Sabbath / Three Faces of Fear / Three Faces of Terror / I Tre Volti della Paura (1963/1964) ***

Black Sabbath / Three Faces of Fear / Three Faces of Terror / I Tre Volti della Paura (1963/1964) ***

The horror anthology movie is something of a lost art. Scads of the things came out during the 60’s and 70’s, and even the 80’s saw a few, but the only theatrically released anthology flick I can think of from the past decade is the mostly forgettable Tales from the Darkside: The Movie. I suppose I shouldn’t be too surprised. After all, the horror anthology film seems to have been primarily a delayed offshoot of the horror anthology comic book, which despite periodic revival attempts has been pretty much extinct since the rise of the Comics Code Authority killed off the EC line back in the mid-1950’s. Today, the sort of hungry, young filmmakers who create most horror films are demographically unlikely to have any first-hand memories of Tales from the Crypt, Vault of Horror, Haunt of Fear, and the rest, while the more recent retro-EC magazines generally either lacked the circulation figures to reach many impressionable young minds (like Twisted Tales, for instance), or were so unbelievably bad that no one could possibly have been inspired by them in the first place (like DC’s miserable Weird War Tales). It’s a shame, though, because a horror anthology done right can be a wonderful thing. And despite a few puzzling defects (which may have been the fault of US distributors American International Pictures, anyway), Mario Bava mainly did it right with Black Sabbath/Three Faces of Fear/I Tre Volit della Paura.

The first story (in the AIP version anyway; I’ll go into as much detail as I’ve been able to find out about the differences later) is called “A Drop of Water,” and it purports to be based on a tale by Anton Chekhov. Nurse Helen Corey (Jacqueline Piereux) receives a phone call in the middle of the night, asking her to come at once to the home of an old woman who worked as a medium (Harriet Medin, from The Horrible Dr. Hichcock and The Whip and the Body). When Helen arrives, the old woman’s maid (Milly Mignone) tells her that her boss has died in her sleep. The maid is not only too frightened of the corpse to permit it to stay in the house even a moment longer than necessary, she can’t even bring herself to come near it to put on its funeral dress. While she shows Helen to the dead woman’s bedchamber, the maid cautions her not to disturb anything in the room but the body itself; the mistress of the house has laid a curse upon anyone who messes with her stuff.

The maid’s warning is enough to deter Helen from tampering with the tarot deck and such, but the nurse forgets all about it when she sees the gargantuan sapphire ring on the dead woman’s finger, and she removes the ring while she dresses the body. A couple of things happen immediately that I’d like to think would change my mind about committing such a theft, but the fact of the matter is that I’m such an incorrigible rationalist that they’d probably have no effect on me at all. First, the ring slips out of Helen’s fingers the moment it clears its owner’s last knuckle and falls to the floor, where it seems consciously to resist Helen’s efforts to reclaim it. Helen knocks over a mostly empty glass of water from the bedside table (she nearly takes out the table, too) while she scrambles for the ring, and no sooner does she get a grip on it than the dead medium’s hand falls from its place on the corpse’s chest onto Helen’s shoulder. Even creepier, in its understated way, is the huge bluebottle fly that insistently comes to rest on the medium’s hand, exactly where the ring had been, no matter how many times Helen shoos it away. The whole business makes Helen more than a little wiggy, and she’s almost as happy as the superstitious maid when at last she completes her task and is able to leave the spooky old house.

But you and I both know what a bad idea it is to countermand the wishes of the dead in a horror movie, and sure enough, Helen does not rest easy when she gets back to her place. First, she finds that her house has acquired a visiting bluebottle as well, and this one is attracted just as magnetically to her finger as the other one was to the medium’s. Then, all the faucets and spigots in her house start dripping, just like the water trickling out of the glass Helen spilled while she scrabbled for the ring. Finally, while Helen frantically runs around turning off the disobedient taps, she begins to feel as though she isn’t alone in her house. She’s not...

“The Telephone” starts out as your common, garden variety telephone harassment horror story, a la When a Stranger Calls and a zillion others. Rosy (Michele Mercier, of And Comes the Dawn... But Colored Red) is getting ready for bed after what looks to have been a difficult day when the phone rings. There’s nobody there when she answers, however. A bit later, it rings again, and as before, nobody responds to her greeting when she picks up. The third time, as Rosy emerges from the shower wrapped in a carelessly arranged towel, the mystery caller at last deigns to speak, and what he says is decidedly unnerving. He likes the way Rosy looks in that towel, he says, but he’d appreciate it even more if she ditched the towel, and just hung around her apartment in the nude. His subsequent calls are just as scary, revealing as they do that the caller can somehow see her everywhere in the apartment. And what’s more, Rosy thinks she recognizes the voice on the other end of the line— the trouble is, the owner of that voice is supposed to be dead!

Rosy immediately calls her friend Mary (Lidia Alfonsi, from Hercules and Messalina vs. the Son of Hecules) to tell her what happened. It seems these two haven’t spoken to each other for some time, and that the ostensibly dead prank caller had something to do with that. It also seems that Rosy was somehow the cause of the caller’s supposed death. Though she doesn’t really believe Rosy is receiving calls from a dead man, Mary agrees to drop in and keep watch over her friend. Mary gives Rosy some tranquilizers before she goes to bed, and after Rosy is sound asleep, the other woman begins composing a letter. It’s addressed to Rosy, and it concerns Mary’s belief that what Rosy needs is a good psychiatrist. But while she’s writing, somebody sneaks into the apartment from behind her, brandishing a pair of pantyhose like a makeshift garrote...

As is customary with these movies, Black Sabbath has saved the best— “The Wurdalak”— for last. On his way to the city of Jassy, the young Count Vladimir D’Urfe (Mark Damon, from Schoolgirl Killer and The Fall of the House of Usher) passes by a black horse, racing like mad with a headless body in the saddle. D’Urfe stops the horse, and his inspection of the body turns up a beautifully crafted dagger in its back. Hoping to learn who the dead man is, who might have killed him, and why, the count takes time out from his trip to search the surrounding hills for any sort of dwelling. At the first house he finds, he receives a none-too-warm reception from its owner, Gregor (Deep Red’s Glauco Onorato), at least until he produces the dagger from the corpse’s back. Gregor completely changes his tune when he sees that. The dagger belonged to Gregor’s father, Gorca, and to judge from the clothes on the body (which Gregor’s brother, Peter [Massimo Righi, from Planet of the Vampires and Maciste in the Land of the Cyclops], runs through with a sword the moment he sees it), the headless man is a notorious Turkish bandit called Alibeg. Gregor and Peter both want to know if D’Urfe found any sign of their father, who had gone out into the mountains nearly five days before with the specific aim of finding and killing the brigand, but from whom they have heard nothing since. Alas, D’Urfe can’t tell them a thing.

As hospitality demands, Gregor and his family offer D’Urfe a place to stay the night, but they also make it perfectly clear that they think the count would be better off if he didn’t take them up on it. Gregor, Peter, their sister, Zdania (Susy Andersen, from Thor and the Amazon Women and Labyrinth of Sex), and Gregor’s wife (The Secret of Dr. Mabuse’s Rika Dialina) all seem to think something very bad is going to happen at 10:00 that night, which will mark the exact five-day point from the time their father went out after Alibeg. Eventually, Vladimir is able to extract an explanation. Rumor had it that Alibeg was more than just a highwayman— he was also said to be a wurdalak, or vampire. Now Gregor’s father had said that he would be back within five days, or not at all. What the family fears is that the old patriarch died fighting Alibeg, and that he will be returning at 10:00 as a wurdalak himself; apparently, the wurdalak always tries to claim those it loved in life as its first victims.

Sure enough, Gorca (Boris Karloff) comes tramping home at the stroke of ten, with what looks for all the world to be a knife-wound in his heart. He acts human enough, though, so his kids don’t quite know what to think, and with great trepidation, they allow him into the house. They’re right to be worried. After everyone goes to bed, Gorca kills both Peter and Gregor’s young son before he is chased away from the house. Count Vladimir at last sees the sense in Gregor’s suggestions that he’d be better off not spending the night, and starts getting ready to split. But he doesn’t want to go alone; he’s fallen in love with Zdania, and he insists that she go with him. After much cajoling, Zdania agrees.

Zdania therefore misses the next nasty turn of the screw, when Gregor’s dead son comes back from the grave, calling for his mother to let him in. The distraught woman is unable to resist the fantasy that her little boy isn’t really dead, and she opens the door, allowing both the boy and Gorca ingress. Gregor and his wife last about 45 seconds after that. Finally, the wurdalaks track Vladimir and Zdania to the ruined cathedral they had been using for shelter since fleeing the family homestead, and attempt to press the point that family comes first, even after death...

At least in its American guise, Black Sabbath is a strangely uneven movie, which seems to bear the marks of extensive tampering by AIP’s editors. To begin with what I have been able to confirm having been done to the film, the original Italian prints open with “The Telephone” and end with “A Drop of Water.” I’d say the Arkoff and Nicholson crew chose wisely in reordering the stories; “The Wurdalak” is so much better than the other two that it really needs to go last. I have also learned that “The Telephone” was cut substantially to eliminate all but the faintest hint of the lesbian relationship between Rosy and Mary, and that “A Drop of Water” was trimmed down, too, for some reason. Knowing this makes some sense of one of the movie’s stranger structural quirks: at over 50 minutes, “The Wurdalak” dwarfs the other two stories, which run scarcely twenty minutes apiece. Other changes look to have been made, but I have been unable to track down anything conclusive about them. For example, I’m not at all sure “The Telephone” was supposed to have a supernatural angle at all. Rosy’s “dead” ex-boyfriend seems far from ghostly when he puts in his appearance at the tale’s climax, and if the story as originally written had Rosy leaving him for Mary (which seems to have been the case), the jilted man’s jealousy would have been enough to drive the story all by itself. I’m also tempted to speculate that Bava’s version did not include the short framing sequences in which Karloff introduces each story. Though the visual esthetic is the same, the overall tone of these scenes is utterly at odds with that of the movie as a whole. Their feel is one of light-hearted comedy, far removed from the gravity of the individual stories, or even from the gallows humor of the EC horror hosts, and all the introductory sequences come across as an intrusion into the film.

But despite the damage wrought by AIP’s tinkering, Black Sabbath remains a solid example of both its peculiar subgenre and work of its director. “The Telephone” is rather weak (although it probably worked better in the Italian version), and “A Drop of Water” seems a bit rushed, but “The Wurdalak” is a fine piece of cinema. Karloff puts in one of the finest performances of his career (and an impressively physical one, given his extremely advanced age at the time) in his only role as a vampire, while the unabashedly folkloric treatment given the monster makes for a welcome change from the usual Stokerisms. That the vampires preferentially attack their loved ones is an especially intriguing touch. Another point in the movie’s favor is the bleak endings of all three stories. We’re in Tales from the Crypt territory here, after all— facile happy endings would be most inappropriate. The main strength of the film, though, is Bava himself, who directs Black Sabbath with a meticulousness that his emphasis on visual style makes easy to miss. Black Sabbath may look loose and dreamy, but examine it closely, and you’ll see that Bava put a tremendous amount of work into giving it that appearance. The style may be similar to that of Corman’s Poe films, but the technique used to produce it is far more considered, leaving nothing to accident.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact