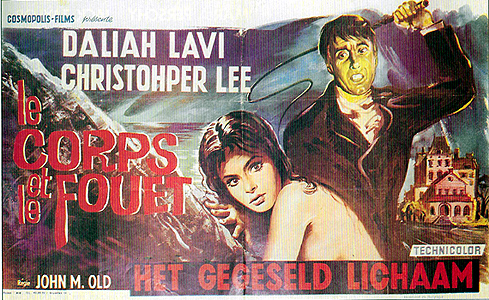

The Whip and the Body / The Whip and the Flesh / Night Is the Phantom / What! / Son of Satan / La Frusta e il Corpo (1963) ***

The Whip and the Body / The Whip and the Flesh / Night Is the Phantom / What! / Son of Satan / La Frusta e il Corpo (1963) ***

I believe VCI Video may be well along the road to atonement for releasing the TV edit of The Night Evelyn Came Out of the Grave and pretending it was the real thing. Of all Mario Bavaís many movies, The Whip and the Body/La Frusta e il Corpo has long been among the most difficult to find. It doesnít seem to have lasted too long in the theaters (the US ones, anyway), its subject matter didnít exactly lend itself to an afterlife on late-night broadcast television (although a severely cut version did air occasionally), and even the advent of home video at the turn of the 80ís (which, as we well know, caused the resurrection of thousands of forgotten stinkers from around the world) wasnít enough to bring it back into circulation. But now the folks at VCI have decided the time has finally come to do something about that, and in marked contrast to their handling of The Night Evelyn Came Out of the Grave, they have committed themselves to doing it right. Not only is the recent VCI edition of The Whip and the Body the first English-language home video release for this movie (hell, it may be the first home video release period), itís also the first chance anyone outside of Italy has had to see the film as Bava intended. Thereís a downside to that in this case, though. Generally, when you hear that somebody has set themselves to the task of dragging the long unseen uncut version of an Italian horror film out of whatever musty crypt itís been reposing in, you build up certain expectations as to the nature of the previously censored content. This is doubly so when the movie has a title like The Whip and the Body. But because The Whip and the Body was originally released in 1963, thereís just no way itís going to live up to the usual expectations; I mean, sureó the Italians were more laid-back about sex and violence than we were in those days, but their movie industry was still pretty straitjacketed. So donít come to The Whip and the Body expecting Twitch of the Death Nerve; expect something like a full-length version of one of the stories in Black Sabbath instead.

Also expect your attention span to get a workout. Bava may drop us right into the middle of something, but itís going to take an awfully long time before it becomes apparent what that something really is. A woman named Georgia (Harriet Medin, from Blood and Black Lace and Death Race 2000) stands in front of a bell jar which contains a red rose and a bloodstained dagger, talking bitterly to nobody in particular. The artifact before her is evidently a sort of shrine to her dead daughter, Tania, who stabbed herself with the dagger as a result of something a man named Curt did to her. Another woman, much younger than Georgia, who goes by the name of Katia (Ida Galli, of Seven Notes in Black and Hercules in the Haunted World), tries to calm her down without much success. This scene is being played out in the castle of Count Menliff (Gustavo de Nardo, from Black Sabbath and The Evil Eye), for whom Georgia works as a maid; Katia, it seems, is one of the countís in-laws. As for the despised Curt, he is the elder of Menliffís two sons, and he has just returned home from a long sojourn abroad. And given that heís being played by Christopher Lee (who vexingly was not hired to dub his own dialogue in the English-language version), Iíd say thereís a very good chance that heís just as potent an avatar of Trouble as Georgia thinks. The other members of the family donít like him any better, either. Curtís father visibly fears him, and has disowned and disinherited him. Little brother Christian (Tony Kendall, from Return of the Blind Dead and The Loreleiís Grasp) not only ended up with Curtís birthright, but with Nevenka (The Return of Dr. Mabuseís Dahlia Lavi), Katiaís cousin and the woman Curt was meant to marry, as well; Christian thus has good reason to be on his guard around Curt. But nobodyís past history with the man is so fraught with potential for bad business in the present as is Nevenkaís.

The day after Curtís return, he catches up with his sister-in-law on the beach overlooked by the castle. Never the sort of man to accept a loss gracefully, Curt begins working on Nevenka the moment he has her attention, plying her with the expected round of I-know-what-you-really-needs and it-was-always-me-you-loveds. Incensed at her exís presumptuousness, Nevenka takes a swing at him with her whip (she had ridden down to the beach on horseback); Curtís reaction is not, one assumes, quite the one she was expecting. Catching the whip in midair and wresting it away from Nevenka, Curts snarls, ďThatís right... You always did love violence,Ē and begins beating her mercilessly. And to judge by the quiescent manner in which she lies there on the sand and takes it, Iím inclined to suspect that Curt knows what heís talking about when it comes to Nevenka and what she does and does not love. It must be some workout Curt gives her, too, because she still hasnít dragged herself home from the beach come nightfall, and everybody else in the castleó that is, everyone but Curtó is worried sick about her and talking about putting together a search party. Curt, as if you couldnít guess, does not join Christian and the others, and it is here that he makes his fatal mistake. While the castle is thus empty but for him (or supposedly so, at any rate), somebody stabs Curt in the throat with that dagger Georgia was mooning over.

Under the circumstances, virtually everyone looks like a suspect. Nevenkaís behavior out on the beach was ambiguous, to be sure, but mightnít her desire to avenge her humiliation be all the stronger if she secretly enjoyed it? Christian, meanwhile, was arguably in a precarious position in regard to his inheritance as long as his older brother was around, and he had let on a couple of times that he was more than a little jealous of Curtís prior relationship with Nevenka. We also know the old count hated Curt more than anybody... well, anybody except Georgia, I suppose. But the question of who killed Curt is soon eclipsed in our attention by the fact that the dead man seems not to care much for staying in his grave; Nevenka begins seeing him in or just outside her room nearly every night. At first, Curtís ghostó if indeed that is what weíre dealing withó is content to spy on her through the window or make menacing gestures at her while standing beside her bed, but before long, Curt gets up to his old tricks. Christian, Katia, and the count may not see the muddy footprints Nevenka swears Curt leaves behind him when he comes into her room, but the welts his whip leaves on her flesh are undeniably the real deal. All the same, Christian still thinks the most likely explanation is that his wife is losing her mind, and he finds comfort in the arms of Katia, who had loved him since she was a little girl. When Nevenka finds out about that, she suddenly seems a little less eager to put a stop to Curtís nocturnal visitations.

Then somebody kills Count Menliff in his bed, using the same familiar dagger, and the murder mystery angle looms up again. But by this time, Curt has begun leaving permanent physical traces behind, and Christian has begun to suspect that, somehow, he may not really be dead after all. As Christianís hunt for both Curt and his fatherís killer (who may or may not be the same person, after all) intensifies, the clues that pile up point in a bewildering array of directions. And, of course, since this is as much a Gothic mystery as it is a horror flick about kinky sex from beyond the grave, we ought to take seriously the possibility that none of those directions is the right one.

I spent the first half of The Whip and the Body thinking Mario Bava was the last person on Earth who should have directed it, and the second half thinking he was just about the only one who could possibly have pulled it off. On the one hand, this is, in the old Gothic tradition, an extremely slow-moving film, and Bavaís ponderous, deliberate style makes the first 45 minutes next to impossible to sit through. The next 45 minutes, however, are another story. After the death of the count, the pace picks up a bit, and as the confusing clues start to pile up, the sort of heavy-handed atmospherics that Bava favored are exactly what is needed for ratcheting up the tension a few notches. And thereís one point on which even this movieís most strident detractors are forced to give the director creditó start to finish, The Whip and the Body is beautiful to look at. That may not be enough to last most people through to the second half, but Iím enough of a sucker for this kind of heavily stylized cinematography that it sufficed to hold my attention until the real story kicked in.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact