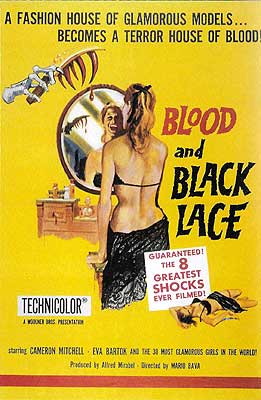

Blood and Black Lace / Six Women for the Murderer / Fashion House of Death / Sei Donne per l’Assassino (1964/1965) ***½

Blood and Black Lace / Six Women for the Murderer / Fashion House of Death / Sei Donne per l’Assassino (1964/1965) ***½

I talk a lot about the origins of the slasher movie, and about its relationship to the giallo— the genre of bloody and highly stylized Italian murder mysteries that are frequently indistinguishable from slasher movies except by the well-practiced eye. What I have yet to do, however, is to discuss the origins of the giallo in more than the most cursory way. Let’s correct that oversight now, shall we? The story really begins with a movie that I’m not comfortable considering a giallo at all, Mario Bava’s semi-comedic Hitchcockian thriller, The Evil Eye. That film established a combination of character types, thematic concerns, and plotting tropes that would remain central to the Italian cinema of serial murder until the 1980’s, when the currents of influence between Italy and North America reversed themselves again. But in style, tone, perspective, and emphasis, The Evil Eye was very much its own thing, little imitated by the mature gialli of the 1970’s. Bava’s follow-up, Blood and Black Lace, was another matter. Although recognizably building upon the foundation laid by its predecessor, Blood and Black Lace represents a nearly complete rethinking of the purpose behind the murder mystery, and in overall effect as complete a break with pervious suspense cinema as any other movie I know of.

Countess Christina Como (Eva Bartok, of Spaceways and The Gamma People) has done quite well for herself since her husband died under somewhat mysterious circumstances a few years back. Together with her lover, Max Marian (Cameron Mitchell, from Island of the Doomed and Gorilla at Large), she runs the Christian Haute Couture fashion salon out of the ancestral Como villa, an enterprise which has brought her a modicum of fame as well as adding to her already considerable riches. Inevitably, however, there’s rot just below Christian Haute Couture’s seemingly glamorous surface. Como’s salon is a veritable cesspit of vice, dissipation, and illegality, where everyone has something to hide and blackmail is a regular part of the social environment. Starting at the top, Christina got together with Max before she became a widow, which tends to make one curious about how she became a widow. Designer Cesare Losarre (Luciano Pigozzi, of Naked You Die and Werewolf in a Girls’ Dormitory) is a hateful old fuck who seems to have something against all of his coworkers. Marquis Richard Morrell (Franco Ressel, from The Sinful Nuns of St. Valentine and Star Odyssey), another designer, gambles with money he doesn’t have. His model girlfriend, Greta (Lea Lander, of Goliath and the Rebel Slave and Rabid Dogs), is a gold-digger who doesn’t realize that the marquis’s wealth does not remotely match his impressive title. Among the other models, Tao-Li (The Hyena of London’s Claude Dantes) is a lesbian, Nicole (Ariana Gorini) is a cocaine addict, and Peggy (Mary Arden, from Revenge of the Gladiators) is covering up an illegal abortion. And then there’s Isabella (Francesca Ungaro). She’s having affairs with both Richard and antique dealer Frank Sacalo (Dante Di Paolo, from The Evil Eye and Atlas in the Land of the Cyclops)— who, by the way, is also dating Nicole, and selling her most of her drugs, too. Isabella keeps Morrell supplied with gambling money, enabling him to maintain the fiction of his playboy nobleman lifestyle. But most of all, Isabella is a keen observer and a careful diarist. She knows every shady thing that goes down in and around the salon, and it’s a safe bet that she’s written all about it in her journal. So when Isabella is murdered on the villa grounds one night by a gauze-masked assassin in black rain gear (now I know where Fantom Kiler got the look for its title character), the possible suspects include almost literally everyone who knew her. Inspector Silvestri (Thomas Reiner) has his work cut out for him.

Of course, there’s one piece of evidence that would probably crack the case wide open all by itself, but Silvestri never sees it. It’s Nicole who finds Isabella’s diary among the possessions she left at the salon, and although Nicole makes a big production of volunteering to take it to the police, any fool can see that she has no such intentions. No one else wants the cops to get their hands on the incriminating book, either, and a dizzying and deadly game of keepaway ensues. As the gauze-masked killer exterminates Christina’s modeling staff, Silvestri battens onto the plausible but mistaken theory that he’s looking for a sadistic sex maniac, and eventually arrests all the men of Christian Haute Couture simultaneously. Even that fails to stop the murders, however, which leaves us with three possibilities: (1). the killer is one of the few women who still remain alive at this point in the story; (2). the killer is someone we’ve never seen before, or have seen so briefly that there’s no credible reason to suspect them; or (3). Mario Bava is so far ahead of the game that there’s more than one killer on the loose already in this, the very first true giallo.

Considering the developmental ties between Blood and Black Lace and The Evil Eye, it would be natural to assume that this movie too took its inspiration from Alfred Hitchcock, making it something like Mario Bava’s Psycho. But Blood and Black Lace actually springs from a different substrate altogether, displaying barely any recognizable Hitchcock influence. Much of the funding for this movie came from the German firm Gloria Filmverleih AG, and by the time Inspector Silvestri is finished with his first round of interrogations, it’s glaringly obvious that Gloria had hired Bava to make them a Krimi. Look at the bizarrely disguised killer, who could easily take his place among the Frog, the Wizard, the Strangler of Blackmoor Castle, and the Monk with the Whip. Consider the tangled web of malfeasance linking the characters, virtually all of whom are guilty of something, so that the only conventional red herring in the cast is the dour and sinister housekeeper (Harriet Medin, from Black Sabbath and The Murder Clinic) who works for several models who share an apartment in an obviously expensive building. That’s an Edgar Wallace trick all the way. Listen to the manic jazz theme music, which sounds more like the work of Krimi mainstay Willy Mettes than anything heard in previous Italian horror movies. And of course, the bare fact that Inspector Silvestri is the closest thing Blood and Black Lace has to a hero (even if he ultimately fails to unravel the mystery) situates this movie in the Krimi tradition, rather than that of Hitchcockiana or any other preexisting strain of suspense picture. That last point is particularly interesting to me, because it makes the police inspector and his role an evolutionary signpost trait, like the toes of prehistoric horses. In a Krimi, the inspector or his private detective equivalent is the hero of the story, who solves the crimes and brings the perpetrator to justice. In a giallo, the cops or detectives are there, but they don’t normally accomplish much. And in a full-blown slasher movie, there’s little to no law-enforcement presence at all.

Still, while it may have been Bava’s brief to make a Krimi, what he actually did was to invent something new. A certain amount of that innovation came simply from Bava being Bava. Take the color cinematography, for example. Bava was a painter before he turned to filmmaking, and lurid use of contrasting colored light to create stylized, otherworldly imagery had been a signature technique of his ever since Hercules in the Haunted World. Blood and Black Lace arguably took it further than his previous work, but in the context of Bava’s career, the difference is merely one of degree. However, if we shift focus to consider Blood and Black Lace not as a Mario Bava movie, but as a murder mystery, a suspense thriller, or a psychological horror film, then we’re very much talking about a difference of kind. There had quite simply never been a film in any of those genres that looked like this one. Hitchcock’s use of color was almost entirely conventional. The black-and-white of the post-Psycho thriller cycle was virtually devoid of recognizable visual style in most cases. Film noir, although highly stylized, used monochrome stock almost by definition. And the look of the Krimis was basically just film noir with umlauts (which makes sense, since noir was basically just modernized German Expressionism without umlauts). Furthermore, Blood and Black Lace applied its surreal, painterly beauty to situations of almost unprecedented ugliness. Seven murders were a lot for 1964, and these weren’t just simple shootings or stabbings of the sort that crime films had traded in since the beginning. Isabella suffers one of the most brutal stranglings on record. Nicole has her face smashed in with the spiked gauntlet of a Medieval suit of armor after a first-person shot establishes that the spikes are pointed straight at her eyes. Peggy is forced face-down against the red-glowing housing of a heating stove. It was as if the audience were wrung through the Psycho shower scene— the standard-setter in those days for cinematic mayhem, except perhaps among those sufficiently hardcore to have seen Blood Feast— at regular intervals throughout the entire film. And on top of it all, there is from beginning to end a gleeful misanthropy on display here, which was equally new to the silver screen. It isn’t just that there are no innocents in Blood and Black Lace— there’s nobody here who wouldn’t sell his or her grandmother to the glue factory for a hot meal. That, too, became something of a running theme in Bava’s work, reaching its stunning apogee in his final giallo, Twitch of the Death Nerve. Taken together, these factors give Blood and Black Lace a malign power that transcends the typical Italian weaknesses of shoddy dialogue, uneven acting, logical lapses, and narrative loose-jointedness. Even today, this movie has bite. Imagine what it felt like in 1964!

Actually, we can do a little better than to imagine it. I’ve long wondered why there are so few recognizable gialli from the 1960’s when Blood and Black Lace is so highly regarded today. Well, it turns out that it was much less so in its own time. Indeed, at home, Blood and Black Lace was a flopasaurus, recouping less than half of its production cost. Beyond that, American International Pictures, which had handled the US distribution of practically every Mario Bava movie since Black Sunday, shied away from this one, considering it far too intense for the teen market that accounted for most of their ticket sales. The film was picked up instead by Woolner Brothers, who were then experimenting with importing edgier material. Where Blood and Black Lace really made its money, perhaps unsurprisingly, was in West Germany. There, it was a big enough hit to bend the Krimi genre in its direction. Most conspicuously, it was only after this movie entered the fray that the dominant Krimi studios, Rialto-Film and CCC, began using color cinematography for their own offerings. The Germans soon started taking other hints from this movie, too. The body counts in Krimis crept upward. Their violence became more graphic. Their villains became more twisted and sadistic. Eventually, another pair of German-Italian co-productions, What Have You Done to Solange? and Seven Bloodstained Orchids, effaced the boundary between giallo and Krimi altogether. But that’s a story for another occasion.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact