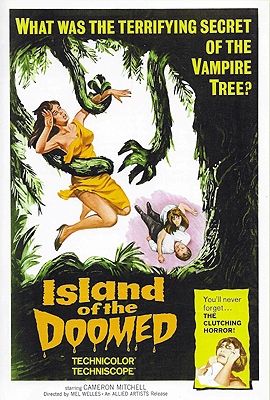

Island of the Doomed / Maneater of Hydra / La Isla de la Muerte / Das Geheimnis der Todesinsel (1967) -***

Island of the Doomed / Maneater of Hydra / La Isla de la Muerte / Das Geheimnis der Todesinsel (1967) -***

It doesnít happen very often, but itís possible for a movie to be both ahead of and behind its time simultaneously. Obviously the rarer an occurrence is, the harder it is to speak definitively about its causes and mechanics. However, it does seem that this strange state of affairs is encouraged by transitions in regimes, so to speak. As old rules, systems, and sets of expectations wither away or come apart at the seams, it is frequently not apparent whatís going to take their places, and creators working under those conditions might be expected to cling to certain familiar forms or techniques even as they push the envelope in other respects. Island of the Doomed makes for a fair illustration of the point. In 1967, when it was made, film industries all over the developed world were entering a period of rapid and drastic change. The fitful, gradual relaxation of censorship standards that had been underway since the early 1950ís (even, by some measures, in Communist countries) was accelerating into something much more sustained and profound. Even so, it would have taken a truly prescient filmmaker to appreciate how quickly the retreat would become a genuine rout, and the onset of the late 60ís was thus attended by considerable uncertainty. This Spanish-German co-production (directed by, of all people, longtime Roger Corman hanger-on Mel Welles) reflects the perplexities of its era by subjecting a shopworn premise to a treatment that anticipatesó but merely anticipatesó the unleashed sleaze and bloodshed of horror movies in the decade to come. Its story of a mad scientist in an isolated hideout devoting himself to the pointless creation of ever more lethal monsters would have seemed familiar to audiences fifteen, 25, even 35 years earlier, but the relish with which Welles depicts the antisocial behavior of monster, creator, and victims alike is more a foreshadowing in milder form of the nasty and amoral 70ís.

The mad scientist here is Baron von Weser (Cameron Mitchell, from Nightmare in Wax and The Toolbox Murders, looking for all the world like a freshly-ironed Jack Palance). Weíre supposed to pretend like we donít immediately know that, but come on. This is a horror movie, and heís a scientistó specifically, a botanistó with a noble title who lives virtually alone on a secluded island. What the hell else would he be doing out there if not building monsters? (Incidentally, the title of the American TV version implies that von Weserís retreat is the Greek isle of Hydra, but I can find nothing in the film itself to support that.) For reasons even more unfathomable than usual, the baronís solitude is about to be intruded upon by a veritable mob of outsiders. These are David Moss (The Invincible Gladiatorís George Martin), a smug jerk-ass who practically cries out to be played by John Ashley; Beth Christiansen (Elisa Montes, of 99 Women and Samson and the Mighty Challenge), who could serve no imaginable purpose but to be Davidís love-interest; James Robinson (Rolf von Nauckhoff, from Liane, Jungle Goddess and Jungle Girl and the Slaver) and his hard-drinking trollop of a wife, Cora (Kay Fisher, of Hard Times for Vampires and The Monster of London City); Professor Julius Demarist (Hermann Nehlsen), a botanist of rather more conventional stripe; and Myrtle Callahan (Matilde MuŮoz Sampedro), noxious comic-relief photographer. Evidently theyíre some manner of tour group, and their guide/driver, Alfredo (Ricardo Valle, from The Awful Dr. Orlof and Hercules Against the Sons of the Sun) has chosen von Weserís island chateau as the next stop on their itinerary. I canít decide whether it counts as good luck or bad that the baronís attitude toward uninvited guests is closer to Charles Gerardís than to Travis Andersonís. Being sent back the way they came from the get-go would surely have disrupted what looks to have been a pretty enjoyable vacation thus far, but then so does all the violent death that ultimately results from von Weserís hospitality.

That death falls first upon someone outside the tour group, however. Not far from the castle, the vacationers encounter a strange, 60-ish man (Deadly Sanctuaryís Mike Brendel) who is clearly in a bad way. Heís much too pale, for one thing, and his jerking, lurching gait can betoken only the most serious of illnesses or injuries. Also, he has lesions on his face in the form of asterisks about the size of a small coin. The man keels over beside the road scarcely five minutes after Alfredo has offered up the curious tidbit that all of the inhabitants save the baron and his household fled the island years ago in a superstitious panic over vampires, and any fool can see both that heís dead and that the most likely cause is blood-loss hugely disproportionate to the size of his admittedly vile-looking open sores. What was that about vampires again, Alfredo? Far be it from this bunch of knobs to let a thing like that put more than a temporary damper on their holiday, though. Or maybe theyíre just taking after their host, who reacts with vague nonchalance to the news that his gardener or whatever just dropped dead of Unexplained Exsanguination Syndrome. Indeed, the visitors all seem much more freaked out by the discovery that the dead man has an identical twin (also Mike Brendel) who up until recently shared the caretaking chores than they are by the mysterious demise of Baldiís unnamed brother per se.

Two matching deaths among their own number are another matter, however. The vacationers retire to their rooms following a stroll around the chateau and a crash-course on the baronís work with the breeding and hybridization of carnivorous plants, but Alfredo beds down right in the front seat of his limousine. Maybe heís afraid raccoons will steal it if he leaves it unattended. In any case, something gets him in short order, without eliciting any notice at all from inside the house. Meanwhile, Cora, Myrtle, and Professor Demarist all get up in the middle of the night for various reasons. Myrtle does so essentially to serve the needs of a future plot point, as we shall see. Demarist means to pester the baron about his hybridization experiments, but gets detoured into pestering Myrtle about nothing in particular instead. Cora, too, has designs on von Weser, but she has no interest in botany. Rather, she wants to charm her way into her hostís bed, much as she had spent the drive to the castle making passes at Alfredo. The baron isnít interested, though, and Cora sullenly, drunkenly stumbles back upstairs, where she meets the same fate as Alfredo not a dozen feet from her slumbering husband. In fact, so unobservant is Mr. Robinsonó and so thoroughly accustomed to Coraís hangoversó that he doesnít notice whatís become of her until the following afternoon. The circumstances of the two deaths are classic murder-mystery bullshitó Alfredo in a locked car with only a few inchesí worth of rolled-down window permitting ingress, and Cora in a similarly locked room nearly 50 feet off the groundó and Myrtle jumps immediately to a bullshit murder-mystery conclusion: Professor Demarist must be the culprit, because he was up and about late at night, and because everyone knows you canít trust a scientist. David prefers to suspect Baldi, becauseÖ well, just look at him. James, for his part, latches onto the rumors that drove away all the islandís villagers, and starts ranting about vampires. Beth entertains no suspicions at alló I told you she was no good for anything. The only one of the travelers who comes anywhere near the truth is Demarist. His analysis of a few of von Weserís hybrids (conducted strictly out of general curiosity, you understand) leads him to fear that one of the baronís experiments has had unforeseen and unrealized results, so that somewhere on the castleís grounds grows a plant (or plants) that has covertly developed a taste for human blood. Demarist is right about the nature of the threat, but fatally mistaken about how it came into existence. Baron von Weser is much too careful in his work to lose control of an experiment the way Demarist envisions, and the night-blooming anthropophagous tree in the reclusive botanistís garden is doing exactly what its creator intended it should.

My fellow B-Master, Liz Kingsley, and I have often lamented the demise of truly mad science in the horror films of recent yearsó of obviously and outrageously deadly research projects with only the most tenuous basis in real-world physics, chemistry, or biology, and with absolutely no practical application that any sane mind could devise. Consequently, Iím thrilled to discover in Island of the Doomed another movie that will hit the spot directly when thatís the sort of mood Iím in. Itís a film that makes no apologies whatsoever for being dumber than the bloody dirt that Demarist spends so much time peering at through his microscope, in a way that you almost never see anymore. Modern sci-fi and sci-fi-inflected horror movies might be every inch as stupid as Island of the Doomed, but more often than not, todayís is a cagier breed of stupidity. Its perpetrators would like to be mistaken for people who have the second clue what theyíre talking about, and thus they generally do sufficient research to acquire the first clue for real. The resulting pictures annoy because they go through the motions of seeking plausibility, but do no more than that. The makers of Island of the Doomed, on the other hand, did not give a ratís hemorrhoidal ass for plausibility as we know it. ďScienceĒ to them was a magic word that could cover for any absurdity. How does Baron von Weser make a blood-drinking tree that can wave its branches around like tentaclesó and more importantly, why? Easyó itís SCIENCE!

Obviously thatís very much an early-30ís mindset, and thus Island of the Doomed displays its spiritual kinship and continuity with the likes of Doctor X and The Vampire Bat. Itís in the presentation that this movie distances itself from that school, and declares its alliance to the harsher, scummier stuff that was just then beginning its rise toward dominance. Take, to begin with, the characterization of the Robinsons. This goes a great deal beyond the old standby of the bickering married couple; what James and Cora bicker about is overtly her debauched infidelity and implicitly his impotence. On the very rare occasions when anything resembling their relationship had been presented in the old days, it was handledó indeed, was required to be handledó with the utmost circumspection and subtlety. You will find only the tiniest trace amounts of either of those qualities anywhere in Island of the Doomed. Now letís look at Myrtle Callahanís and Baron von Weserís death scenes. Nowhere outside of a Herschell Gordon Lewis movie would anyone have seen more lavishly explicit carnage in 1967. In fact, Cameron Mitchell, who thoroughly disapproves of onscreen gore in horror movies, cites Island of the Doomed among the films he acted in that he refuses to see. Nor is it simply a quantitative matter of all the buckets of stage blood being slurped up by the pistils of the killer treeís flowers. Thereís a feeling of sick glee in those scenes, much like in the two killings that constitute the finale of The Brain that Wouldnít Die. And finally, thereís the matter of Baron von Weserís relationship with his creation. Plenty of mad movie scientists are fiercely proud of their monsters, but von Weser is far more twisted that. Thereís a vague but unmistakable note of eroticism in the baronís utterances whenever he speaks to or about his vampire tree, notable most especially in the final scene, as they inevitably go down in death together. Simply put, the experiments that created the tree arenít half as unnatural as von Weserís feelings for it now that itís here. All in all, I see now why I thought at once of John Ashley the first time David Moss caught the cameraís attention. With its artless combination of old-fashioned subject matter and newfangled sleaze, Island of the Doomed is practically a European counterpart to the cheap, lurid horror films that Ashley was headlining over in the Philippines around the same time.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact