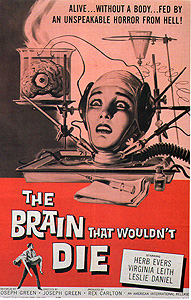

The Brain that Wouldn’t Die/The Head that Wouldn’t Die (1959/1962) -****

The Brain that Wouldn’t Die/The Head that Wouldn’t Die (1959/1962) -****

This is another one of those films that have the power to transform ordinary, respectable people into slavering B-movie maniacs. I first saw The Brain that Wouldn’t Die on “Creature Feature, with Count Gore DeVol” when I was about five years old; amazingly enough, WDCA-20 aired an uncut print, and I was absolutely blown away. There is almost nothing you could ask for in a late-50’s mad scientist movie that The Brain that Wouldn’t Die doesn’t deliver, and as if that weren’t enough, it throws in a bunch of other stuff that you’d never think to ask for in the first place. It’s hard to believe producer Rex Carlton had to shop this flick around for more than three years before he could secure a distribution deal that was to his liking.

We begin by establishing the credentials of our mad scientist. A surgeon named Dr. Cortner (Bruce Brighton) has just failed to save one of his patients. The moment Cortner decides to call time of death, however, his partner in the surgery— who turns out to be his son, Bill (Herb Evers, who appeared in Fer-de-Lance and Claws under the name Jason Evers)— asks to try again using a technique of his own. The elder Dr. Cortner resists for a bit, but is eventually persuaded by the argument that since the patient is already dead, an experimental approach could do him no further harm. The younger Cortner sets his father to massaging the dead man’s heart and applying direct electrical stimulation, while he himself opens up the skull and begins pumping electricity into the motor regions of the patient’s brain. After just a few minutes, the supposedly dead patient is registering a strong and steady pulse, and his heart continues beating even after the doctors cease administering the electricity. Cortner Sr. is forced to concede that his son’s experiment has panned out, although he inexplicably continues to express disapproval of the line of research that led Bill to it. The burgeoning dispute is cut short, however, when the two men are interrupted by nurse Jan Compton (Virginia Leith, who had previously appeared in much more sober films like On the Threshold of Space), Bill’s aggressively amorous fiancee. Apparently it’s quitting time on Friday, and Jan is eager to hear what Bill has planned for the weekend; in particular, she’s curious as to whether Bill is finally going to take her out to his family’s “old country place,” where he has recently been in the habit of making solo weekend retreats. Cortner Sr., as it happens, doesn’t approve of that, either. It’s enough to make you wonder whether there’s anything that does meet with the old grump’s approval!

Through a series of unexpected events, Jan is indeed about to see the house in the country at long last. While she and Bill are on their way out of the hospital, another nurse snags them, and tells Cortner that somebody named Kurt (Leslie Daniels) has called for him, saying that something terrible has happened, and that Bill is needed at the country house right away. (Incidentally, we never will learn just what pressing calamity has Kurt so riled up.) It isn’t exactly what Bill had in mind, but given that he’s already got Jan with him, he may as well bring her along on his enigmatic errand. Such is the urgency with which Cortner drives, however, that he loses control of his car while rounding a bend perhaps a quarter of a mile from his destination. The car crashes through the guard rail, and Bill is thrown from the cabin; he’s just lucky the slope of the embankment where he lands is made of soft ground. Jan has not been so fortunate, though. The car is on fire when Bill reaches it, and since the object he wraps in his jacket and pulls from the wreckage is much too small to be a woman’s body, I’m thinking Jan is pretty well screwed. The strange thing, however, is that Bill’s first words to Kurt (who we can now see to be Cortner’s assistant in that research his father doesn’t like) after sketching out the accident are, “I have to save her!” Leaving Jan to burn in the ruins of the car would seem to be rather counterproductive to an such enterprise, wouldn’t it?

Perhaps, but then again, we haven’t yet seen what Bill salvaged from the car. Inside the bundle of his jacket is Jan’s head, which was severed in the crash. With the help of his newly perfected adreno-serum, Bill believes he can keep his girlfriend’s head alive for a good 50 hours, more than enough time, or so he reckons, for him to find her a new body and perform a transplant. Cortner has said nothing about it to anyone else, but out at the country house, he and Kurt have made enormous strides in the science of tissue grafting and organ transplantation— and, as we have already seen, emergency resuscitation measures— and damned if Jan’s head doesn’t come right back to life once Bill has it set up in a pan full of electrified, chemically treated blood. Jan herself is none too pleased to be restored to life as a disembodied head, but sometimes we all have to settle for less than we want, I suppose.

In any case, Bill now has about two days to hook Jan up with a new chassis, and I for one don’t see any female cadavers lying around in Cortner’s basement laboratory. (For that matter, I don’t see much in the way of lab equipment, either…) As you’ve probably guessed, this means that Bill is going to have get a new body the hard way, from a donor who is not necessarily ready to part with it yet. His first stop is a strip club called the Moulin Rouge— obviously we are dealing here with a man who cares enough to give the very best. For a while, he thinks maybe the blonde stripper (Bonnie Sharie) who took a pronounced interest in him the moment she saw him standing at the bar is the girl he’s looking for, but then another dancer (Paula Maurice) gets jealous, and tries to muscle in. Whichever girl Cortner were to pick, the other would surely remember him, and would probably make the connection very quickly when her rival failed to show up for work the next day. Thus Bill gives up on them both, and makes his exit from the Moulin Rouge— leaving the two strippers locked in a furious catfight as he does so.

The next day, Bill runs into Peggy Howard (Frankenstein Meets the Space Monster’s Marilyn Hanold), a former nursing intern who used to work at the hospital with him, and again thinks he’s found the body he’s looking for. But no sooner has Peggy hopped into the car with him than her friend, Donna Williams (Lola Mason), comes walking up the street, and Bill finds himself right back where he was the night before (except without the catfight). On the other hand, both women are supposed to be acting as judges that night for a local beauty pageant, which seems like as good a place to go body-shopping as any. What’s more, Peggy mentions in passing an old and hitherto forgotten acquaintance of Bill’s, a model named Doris Powell (Adele Lamont), who has the most beautiful body either one of them can remember seeing, but who has become an almost total shut-in ever since her face was scarred by a psychotic ex-boyfriend in a fit of jealous rage. If Bill is seeking a looker nobody would miss, he couldn’t do a whole lot better than her.

But while Bill is out trying to pick up chicks, something is going on back at the homestead that he really ought to know about. The chemicals he’s using to keep Jan’s head alive and receptive to transplantation have had an unexpected side-effect, in that they have left her able to communicate telepathically with anyone else that has been exposed to them. That might seem a trivial development at first, but that’s only because I haven’t yet mentioned the closet in the basement lab. Locked behind its stout, oaken door is a thing that Kurt describes as “the sum total of all Dr. Cortner’s mistakes.” This creature, which started out as nothing more than “a mass of transplanted tissue” before Cortner brought it to life, was animated using an earlier, less perfect form of the treatment Bill used on Jan, meaning that she now has the ability to link minds with it. Whatever else their differences, she and the Closet Monster are in full agreement in their hatred for the man who gave them their respective mockeries of life, and both are just itching for revenge. Kurt is the first to feel their wrath. After being toyed with and terrorized from the moment Jan first establishes contact with the thing in the closet, Kurt is goaded into an act of carelessness while bringing the creature its dinner. The thing reaches out through the open hatch in the door to its prison, seizes Kurt by the right arm, and rips the limb from its socket. The irony here is that Kurt’s entire reason for collaborating with Cortner is that their research seemed to promise to restore the use of his other arm, the withered condition of which prematurely ended his own career as a surgeon. When Bill comes home with Doris and finds Kurt’s dismembered body in the basement, he begins to see just how far out of hand things have gone in his absence. Little does he realize that they’re about to go further out of hand still.

One of the most fascinating things about The Brain that Wouldn’t Die is the marked thematic resemblance it bears to another mad doctor movie from 1959, Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face. What makes the similarity so remarkable is that it is almost certainly a total accident; Franju can hardly have influenced writer/director Joseph Green, because Eyes Without a Face didn’t make it to the United States until 1962— the same year The Brain that Wouldn’t Die finally escaped from distro limbo! The same basic setup— a guilt-crazed doctor does the unspeakable to repair a grievous injury he accidentally inflicted upon somebody he loves, irrespective of her wishes— drives both films, but for once, the American version came out sleazier and more exploitive than the European. The Franju movie is brooding and somber, and mostly works through understatement. The Brain that Wouldn’t Die is gleefully crass, with a pervasive atmosphere of loutish, leering sexuality that far outstrips the likes of Atom-Age Vampire or The Awful Dr. Orlof, even without any actual nudity, and a take-no-prisoners attitude toward gore and violence that would not be exceeded in the West until Hershel Gordon Lewis unleashed Blood Feast in 1963. And to top it all off, The Brain that Wouldn’t Die features plotting and dialogue so insane that it can easily play in the same league as any of its counterparts from France, Spain, or Italy.

To begin with the sex, The Brain that Wouldn’t Die suggests what might have happened if Hugh Hefner had financed a horror movie at the turn of the 1960’s. It isn’t just the cat-fighting strippers, the photographic feeding-frenzy that accompanies the introduction of Doris Powell, or the meat-market vibe given off by the beauty contest, although all of those things are major contributors. Everything from Jan’s blatant come-ons in her first appearance onscreen to the smarmy manner in which Bill charms his way past Doris’s “I hate all men!” act (that’s a straight-up quote, by the way) to seduce her to her intended doom makes this movie feel as though it had been left to steep for days at a stretch in the essence of late-50’s men’s magazines. Then there’s the music. Most of the score is just unusually well-chosen library music, but Bill’s hunting scenes are always accompanied by an original piece called “The Web,” by Abe Baker and Tony Restaino, which features some of the most unctuous porno-sax to be heard in any film prior to the 1970’s. There may not be much in the way of bare flesh on the screen, but the tone of this movie is almost unbelievably smutty for its time.

As for violence, it’s no wonder American International Pictures cut out the two big gore set-pieces when they gave The Brain that Wouldn’t Die its first go-round in 1962. The appallingly grotesque monster makeup for the thing in the closet and the open-brain surgery in the first scene were pretty strong stuff for those days, but nothing you couldn’t see in a Hammer Frankenstein flick. The death-scenes of the two mad scientists are another matter, however. When the Closet Monster yanks Kurt’s arm off, it takes him an incredible two solid minutes to finish dying; he spends those minutes staggering all over the house in an apparent effort to smear his copiously bleeding stump across every wall, floor, and furnishing in it. Cortner’s death goes even further, in its way, in that after the monster rips out his throat with its teeth, it makes a point of holding a clot of mangled, bloody flesh up to the camera for the audience’s approval. Now do you see why it awes me in retrospect that my local UHF station would broadcast an intact print of this film back in 1979?

Finally, the grindhouse precocity of The Brain that Wouldn’t Die is mated to a script that might as well have been imported from another planet. What else are we to make, for example, of Bill Cortner’s glib assurance to Kurt that the police won’t be showing up to ask questions because Jan’s body was burned to a crisp in the car? I don’t know about you, but where I come from, charred, headless bodies by the side of the highway attract a fair amount of attention from law-enforcement professionals of every stripe. Then again, since we never do see a single cop in this movie, I guess Cortner knows what he’s talking about after all. The dialogue, meanwhile, is nearly Shakespearean in its top-heavy excess. Take a gander at what Kurt has to say in response to Jan’s questions about what lives in Bill’s closet: “There is a horror beyond yours, and it’s in there, locked behind that door! Paths of experimentation twist and turn through mountains of miscalculation, and often lose themselves in error and darkness.” I hasten to remind you that the audience for this pronouncement is a woman’s severed head, surrounded by scientific widgetry and sitting in a pool of blood in a dissecting tray— few things I’ve seen have been more surreal. Yet somehow, Green manages to keep a sense of humor at the same time, as evidenced by the ongoing conversation between Bill and Doris. Doris’s dialogue may be as stilted and lumpish as anything in Swamp Women, but Bill gets some brilliantly ironic one-liners, which Herb Evers delivers with the perfect deadpan tone. All in all, The Brain that Wouldn’t Die comes across as a movie made by lunatics whose moments of lucidity are even more alarming than the incoherent rantings they punctuate. Small wonder that it has become one of the world’s few legitimate cult classics.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact