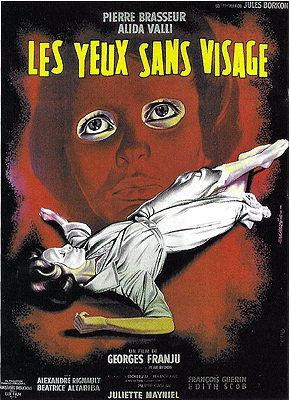

Eyes Without a Face / The Horror Chamber of Dr. Faustus / House of Dr. Rasanoff / Les Yeux Sans Visage (1959/1962) ***½

Eyes Without a Face / The Horror Chamber of Dr. Faustus / House of Dr. Rasanoff / Les Yeux Sans Visage (1959/1962) ***½

Here’s a possibility to ponder: What might have happened if The Brain that Wouldn’t Die hadn’t been stupid? No, really; think about it. The idea of a man who has accidentally done something unspeakably awful to a person he loves, for whose sake he now deliberately does even more unspeakable things to strangers while the object of his twisted benefice can only look on in impotent horror is a potentially powerful one. Imagine if writer/director Joseph Green had aspired to make more than a nasty little exploitation movie, had hired himself a cast of actors whose skills were equal to a more serious treatment, and had devised a screenplay that offered something a tad more sophisticated than Closet Monsters and Jan in the Pan. It might raise a few hackles for me to do so, given this movie’s elevated reputation, but allow me to suggest that a smarter The Brain that Wouldn’t Die might have come out looking a lot like Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face/Les Yeux Sans Visage.

I’ve always liked it when a movie begins with a scene that seems to say, “Something really awful is going on here, but don’t you go expecting us to tell you what it is yet,” and Eyes Without a Face starts off with a stellar example of the form. A shifty-eyed blonde woman (Alida Valli, from Eye in the Labyrinth and Suspiria) drives her crappy little Citroen down an otherwise deserted road in the middle of the night. There’s someone in the back seat, slumping motionless and bundled up completely in an overcoat and fedora. Eventually, the woman reaches the banks of the Seine, at which point she gets out of the car and pulls her passenger from the seat. Judging from the smooth, pasty-white legs sticking out from under the hemline, I’d say the passenger is a young woman, and I’ve also got a sneaking suspicion she’s naked under that coat. I’m also going to go out on a limb here, and suggest that she’s probably dead, too. Yup. In fact, Ms. Shifty Eyes has driven out to the river with the express purpose of dumping her lifeless passenger into it.

The police find the body a few days later, and it is revealed that the night’s activities were even more sinister than they had appeared. Ms. Shifty Eyes had that fedora pulled down over the dead girl’s face in order to conceal the fact that she didn’t have one! This, of course, makes identifying the body rather complicated. The cops call in two men, both of whom have teenage daughters who had gone missing at about the same time that the medical examiner believes the mystery girl died. One of these is just some guy; the other is a respected surgeon named Dr. Genessier (Pierre Brasseur), who was brought in specifically because his AWOL daughter had previously been maimed in a terrible auto wreck— her face was literally torn from her skull by the shards of the shattered windshield. Genessier has one look at the body in the morgue and knows that it’s his Christiane.

But is it really? When Genessier comes to his daughter’s funeral, he brings with him not only Christiane’s fiance, Dr. Jacques Vernon (François Guerin), but his own secretary, Louise, as well. And Louise, as you’ve probably guessed, is Ms. Shifty Eyes herself. Our suspicions are confirmed when the camera follows Genessier and Louise back to the doctor’s house, a big, creepy mansion just a few thousand feet from the hospital where he works. Upstairs in one of the bedrooms is a teenage girl (Edith Scob), lying on her bed with her face buried in the pillows. Both Genessier and Louise make an effort to comfort her, saying that they are sure it will work next time, and that she’ll be beautiful again, just like she was before the accident. And yeah, that means exactly what you think it means.

The reason why the otherwise decent Dr. Genessier has begun stealing the faces off of pretty girls is because he was driving the car when the disfiguring crash occurred. What’s more, he was driving like a fucking maniac, and he knows it. Thus overcome by guilt, he is now focused singlemindedly on repairing Christiane’s ravaged face, as he once did for Louise. Christiane is in significantly worse shape, though, so a simple graft here and there just isn’t going to cut it; the only thing for it would seem to be hooking her up with an entirely new face, all in one go. Your average teenage girl is rather, well, attached to her face, however, so Genessier isn’t terribly likely to have volunteers beating down his door. And thus we have his arrangement with Louise, who goes around befriending girls in downtown Paris only to lead them into the doctor’s clutches.

Louise’s next target is named Edna (Juliette Mayniel). Louise accosts her in line at a theater, claiming that the friend with whom she had planned to see the show hasn’t shown up, and that she therefore has a spare ticket. Edna can have it, if she wants, and she needn’t even pay for it. A few days later, once Louise has learned that Edna is looking for a room to rent, she brings her back to Genessier’s place, where the doctor’s hospitality includes a chloroform-soaked rag and a locked room in the cellar. The subsequent face-flaying scene hits about as hard as anything would be permitted to in 1959; in fact, I’m amazed it didn’t end up on the cutting-room floor when Eyes Without a Face made it to the States three years later. (And while we’re on the subject of this movie’s American release, I’ll never understand why the US distributors decided to re-title it The Horror Chamber of Dr. Faustus. Sure, that’s an okay exploitation title, but Eyes Without a Face is so much creepier…) At first the operation appears to be a success (although Edna is understandably so despondent over what has happened to her that she throws herself to her death from a top-floor window as soon as she is able to escape from her cell), and it seems that Christiane will have no more use for the porcelain mask she’s been forced to wear in the months since the accident. But after a couple of weeks, it becomes obvious that her body is rejecting the graft after all, and Genessier is forced to remove the secondhand face on the 20th day after the initial surgery.

Meanwhile, the police have noticed Edna’s disappearance. Sure, she was from out of town, but she had at least one friend in Paris, and that friend was present on at least one occasion when Edna met up with Louise. Edna’s friend is thus able to tell Inspector Parot (Alexandre Renault) about the missing girl’s relationship with a somewhat older woman who always wore a choker-style necklace composed of several strings of pearls. (The pearls are Louise’s stylistic trademark, if you will. She wears them at all times to conceal the one scar that Genessier couldn’t do anything about.) This may not seem like much to go on, but Parot gets lucky. He and Jacques Vernon became friends while the former was investigating the disappearance of Christiane Genessier, and the young doctor still drops by to talk to the detective every once in a while. One of these visits happens to coincide with Parot’s interview with Edna’s friend, and Vernon gets a funny feeling when he hears that Edna had gotten into the habit of hanging out with a pearl-necklaced blonde woman a good decade older than her. The description sounds an awful lot like Dr. Genessier’s secretary to him. Now the case of Genessier’s last victim is still officially unsolved (we know she’s been substituted for the supposedly dead Christiane, but the police don’t), and it swiftly occurs to Parot that Edna and the other missing girl are about the same age, and were both described as being good-looking, with dark blonde hair. This gives him the idea that the two disappearances are related, and thanks to Dr. Vernon, he’s even got a suspect. Serendipity smiles on Parot again when one of his beat cops brings in yet another girl in the same age bracket on shoplifting charges. Her name is Paulette (Beatrice Altariba), and Parot offers to drop the charges against her if she’ll agree to help him crack the case of the vanished girls. All she has to do is dye her hair the right color, and pretend to be sick.

Well, that and take the risk of having whoever is doing the kidnapping set his or her sights on her. In fact, that’s really the entire point of the exercise. Paulette checks herself into the hospital where Genessier and Louise work, complaining of strange, severe headaches. As Parot is hoping, this does indeed bring her to Louise’s attention, but she and her boss move too fast for the policeman. No sooner has Paulette been released from the hospital than she is offered a ride into town by Louise, who then takes her instead to the Genessier house. But fortunately for Paulette, neither Louise nor Dr. Genessier has banked on Christiane. Her recent experience with the failed graft has convinced her that she’ll never be normal again, and she doesn’t want to see any more innocent girls futilely sacrificed on her behalf. And since Christiane is the only one in the house who’s ever been nice to all those huge, caged dogs her father’s been using as experimental animals, her opinion on the subject is something that Genessier really ought to take into consideration.

Like I said, if The Brain that Wouldn’t Die hadn’t been stupid… You’d expect quality work, though, considering that the screenwriters also wrote the novels on which Vertigo and Diabolique were based. The story moves a bit too slowly for its own good, but everything else about Eyes Without a Face is so right that it’s no wonder one European filmmaker or another seemed to make a ripoff of it about every three months during the 60’s. (And Jesus Franco, bless his heart, was still at it as late as 1988!) It was supposedly Georges Franju’s intention to steer well clear of just about anything that had previously been done in the horror genre, and though he wasn’t entirely successful in that endeavor, he did at least put a noticeable new spin on everything he did borrow from somewhere else. To begin with, there’s nothing about Dr. Genessier that makes you say, “That man is a mad scientist.” Genessier is soft-spoken, professional, and obviously very attached to his daughter. Too attached, as it happens. Whereas most mad movie scientists are motivated by a desire for glory or by some quixotic drive to make the world a better place, Genessier just wants to make amends for his stupid mistake which has cost Christiane so dearly. His guilt-fueled obsession becomes so strong that it blinds him not only to the moral ugliness of his actions in its pursuit, but even to the fact that its supposed beneficiary is more opposed to those actions than anybody.

That brings us to Christiane. In this movie with no heroes in the conventional sense, she ends up being the focus of attention, even though she’s only rarely onscreen. After all, none of this would be happening if it weren’t for her and her mutilated face. She’s also the eeriest thing in the movie, a virtual living ghost. With her reclusive ways and her nearly weightless walk and her huge, dark eyes staring with equal measures of sorrow and reproach from the sockets of her expressionless porcelain mask, she really does seem almost like a supernatural presence. And it would be entirely fair to say that she haunts the rest of the characters. In addition to driving her father to madness simply by existing in her present form, she also exerts her influence over Jacques Vernon. Almost every night, she calls him on the telephone and listens silently to his increasingly exasperated “Hello? Hello?!” She can say nothing to him, of course, for she is supposed to be resting quietly in her tomb, but Jacques nevertheless seems to suspect at some subconscious level who his tormenting caller is even before the night when Christiane forgets herself and whispers a single word to him. She is also, morally speaking, the most complex character in the film. For despite her oft-professed disbelief in her father’s ability to restore her appearance, and despite the revulsion she obviously feels at the methods by which he seeks to do so, Christiane never lifts a finger to stop him until two other girls have died and a third is set up to follow them. And, really, why would she? Who wants to go through life with nothing but a huge, featureless scar for a face— especially when a chance, no matter how remote, exists that the damage can be repaired? We can therefore feel pity for her, but she’s as menacing as she is sympathetic. That porcelain mask and the barely-glimpsed horror that lies behind it give Christiane a terrible dignity, and it seems foreordained from her first appearance that she will be the one to unleash the violence we know must come in the end. (Incidentally, Franju made a very smart move regarding Christiane’s real face. We do get to see it, and at quite close range, but because the scene is shot from the perspective of the drugged Edna, it is far too blurry to expose the shortcomings of the makeup effect. All we can see for certain is that Christiane’s face is dark and raw and seamy, contrasting starkly with the vivid whites of her eyes. It’s the best of both worlds, providing the necessary horror film money shot while also implying far worse things than could be realized within the limits of 1950’s budgets and technology.) Every movie ought to have something— an image, a scene, an exchange of dialogue— that no attentive viewer can ever forget, and Eyes Without a Face has that in the form of its not-quite-title character.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact