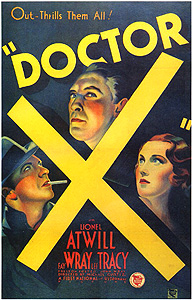

Doctor X (1932) **

Doctor X (1932) **

It’s tempting to speculate about what might have been had one of First National’s 1928 projects gotten off the ground. First National is a studio that nobody much remembers today, but it had been a fairly major player during the silent era; the pioneering Willis O’Brien monster film The Lost World had been a First National production. The company fell on hard times soon thereafter, however, and by 1928, its finances were in such a state of shambles that its owners would decide to sell out to Warner Brothers. Things might have turned out very differently, though. Just a little while before First National went bust, the studio had hired O’Brien back to help them develop a feature-length film version of Frankenstein (the first in American release since the lost and mostly forgotten Life Without Soul more than a decade before). Just imagine a Frankenstein movie with an O’Brien-animated monster— man, that would have been cool! And I bet it would have made a shitload of money, too— possibly enough to stave off fiscal disaster and keep First National in the big leagues during the decade to come. But for some reason, the Frankenstein project never came together. First National didn’t entirely cease to exist, however. Instead, it passed on into a strange afterlife as Warner Brothers’ semi-independent B-unit, and when horror movies started to look like the wave of the future after Universal’s success with Dracula and Frankenstein, Warner released most of their efforts in the genre under First National’s imprimatur. The first such film, little seen until comparatively recently, was Doctor X.

Doctor X is an odd little movie. It exhibits a peculiar mix of the daring and the dated that imparts to it a certain level of interest despite its shambling, structurally awkward script, somewhat haphazard direction, and annoying cheater ending. On the one hand, Doctor X features a surfeit of corny comic relief and a great many hokey, naive “scare” scenes that would seem more appropriate in a 4-H Club haunted Halloween hayride than in any remotely serious horror flick. Then again, it also has serial murder, cannibalism, some of the ickiest mad science of the 1930’s, and a hell of a lot of scantily clad (at least by the standards of the era) Fay Wray. And— amazingly, considering that it was made by a B-division in the depths of the Great Depression— it was originally shown in two-strip Technicolor, although many reissue prints are in black and white.

The first character we meet is a reporter named Lee Taylor (Lee Tracy); hardened veterans will find this alarming because in horror movies of this vintage, the first character introduced is nearly always the central player, while the reporter is almost invariably the comic relief. Few things in this business are more annoying than movies where the comic relief is allowed the hero’s share of the screen-time. Anyway, this Lee Taylor is poking around in the vicinity of the city morgue, to which a pair of police detectives (Willard Robertson, from Supernatural and The Monster and the Girl, and Thomas E. Jackson, from Valley of the Zombies and It Conquered the World) are escorting the latest victim of the Moon Killer. The Moon Killer, in case you couldn’t guess, gets his name from the fact that he strikes only on nights of the full moon; Taylor will later repeatedly assert that the murders are the biggest story to hit town in the last six months, and he is understandably determined to find a way into the morgue to eavesdrop on the police. Eventually, Taylor manages to sneak in disguised as a cadaver himself, and he thus has a front-row seat to the show while the detectives talk the case over with Dr. Xavier of the Institute for Medical Research (Lionel Atwill, of The Vampire Bat and Son of Frankenstein, in the role that started his fifteen-year career as a second-tier horror star).

Upon examining the body of victim number six, Dr. Xavier gives his opinion that the dead woman was first strangled, then stabbed in the back of the neck with some sort of surgical instrument, and that the large hunk of flesh that was removed from her shoulder was neither cut nor torn out, but rather eaten. Apart from the specific nature of the crime being discussed, this looks to be a fairly ordinary cops-and-medical-examiners scene, but then the two detectives do something completely unexpected, and begin grilling Dr. Xavier as if he were a suspect himself! In fact, he is. You see, the police have their own medical examiner, and he has determined that the neck wounds found on all the Moon Killer victims were made by a “brain scalpel,” an instrument so specialized that in all the country, only Xavier’s institute is known to use it. And backing up that odd piece of evidence is the fact that all six Moon Killer murders occurred within mere blocks of the Medical Research Institute. Combine those two details with the extraordinary precision with which the scalpel wounds were inflicted, and it makes for a strong circumstantial case that either Xavier or one of his fellow researchers is the culprit.

Eager to deflect blame away from himself and his organization, Xavier agrees to introduce the two policemen to all of his colleagues. As it happens, this has an effect almost precisely opposite to the one Xavier intended. Dr. Wells (Preston Foster of The Time Travelers) might have a hard time in the strangling business, what with his missing left hand, but he is an avid student of cannibalism, and he does things like keep human hearts alive in tanks on his workbench. Doctors Haines (John Wray) and Rowitz (Arthur Edmund Carewe, from The Mystery of the Wax Museum and the 1925 The Phantom of the Opera) were both shipwrecked together on an island near Tahiti, and the third member of their party disappeared mysteriously before they could be rescued— think one of those guys might have a copy of The Donner Party Cookbook on the shelf above his stove? And to make matters even worse, Dr. Rowitz and another scientist named Duke (Murders in the Zoo’s Harry Beresford) are currently studying the effects of moonlight on abnormal psychology! The detectives go back to the station suspecting everyone, and Xavier is able to avoid having the lot of them hauled off to jail only by promising to conduct an investigation of his own.

Meanwhile, Lee Taylor has left his hiding place on the shrouded gurney and snuck out onto the fire escape to spy on the conversation more effectively. This brings him into contact with Xavier’s daughter, Joanne (Fay Wray, from King Kong and The Most Dangerous Game), who happened to be on her way to talk to her old man when the reporter climbed out the window. Joanne doesn’t buy Taylor’s story that he’s a building inspector, and she sends the reporter packing at gunpoint. So you can imagine how pleased she is to see him the next day when he gains entry to the Xavier mansion on false pretenses in order to steal photographs of the doctor and his offspring. Taylor gets rebuffed again, but this time, the girl knows who he really is— his paper ran a story under his byline reporting the suspected link between Xavier’s institute and the Moon Killer in its morning edition. The reporter gets what he really wants, though, in that Joanne lets it slip out that her father has gone to his summer home at Black Shoals with his four colleagues. Taylor makes the connection that his unwitting informant does not, and realizes that Xavier wants to use the privacy of this remote dwelling to facilitate the investigation the cops want him to perform; Taylor is cab-bound for Black Shoals in no time at all.

And now, oddly enough, Doctor X turns itself into something very much like an old-fashioned locked-room mystery. Xavier’s plan is to hook all of his colleagues up to what amounts to an extra-snazzy polygraph, and subject them to the sort of stimuli he believes trigger the Moon Killer’s psychotic episodes. The experiment is to be conducted at night, by the light of the full moon, and will have as its centerpiece a reenactment of one of the crimes performed by Xavier’s butler, Otto (George Rosener, of Sh! The Octopus), and maid, Mamie (Mark of the Vampire’s Leila Bennett). Taylor— unbeknownst to the doctor, of course— will be sneaking around backstage while all this goes on, sniffing for a scoop. He gets one, alright. At the climactic moment of the servants’ performance, the lights suddenly go out, and somebody kills Dr. Rowitz! Even the reporter, who is discovered hiding in a closet in the subsequent search of the area, saw nothing, as he had been gassed into unconsciousness right before the blackout. The upshot of it all is, Xavier and his colleagues now know for certain that one of them is the Moon Killer, but they’re not really any closer to determining which of them it is.

Thus it is that Xavier repeats his experiment the following night, and this time, an answer is forthcoming. Understandably reasoning that the one-handed Dr. Wells is beyond suspicion, Xavier exempts him from the test, and has him run the show instead; the other doctors want to make sure Xavier is tied down just like the rest of them— after all, he could just as easily be the killer himself. There’s a second difference this time, too. Mamie wants nothing more to do with Xavier’s experiment after what happened last night, so Joanne volunteers to play the victim’s part. But while she and Otto and the other scientists are getting everything together, Dr. Wells sneaks back to his room where, slipping off his artificial hand, he opens up a cabinet and removes a second, far less artificial-looking one. “Synthetic flesh...” he moans contentedly in a voice I more commonly associate with Homer Simpson rhapsodizing about beer or donuts as he slips the new forearm over his stump, and then gets to work molding himself a new face with more of his “synthetic flesh”— which in this case looks just like a big vat of cheap-ass putty makeup. (Gee, do you suppose that’s what it really could have been?) Thus equipped, Wells heads back to the experimental chamber, coldcocks Otto, and then takes his place in the murder vignette. The idea here, obviously, is that Wells means to kill Joanne for real, but he is foiled when Lee Taylor comes bursting into the room. The reporter and the mad scientist have one of those typically unconvincing 30’s/40’s action-movie fights, and in the end, Dr. Wells goes plunging to his death from an upstairs window. And because this is 1932, Taylor gets the girl, even though there’s no real reason why he should.

It’s easy to get the impression, watching Doctor X, that nobody involved in its creation was quite sure what they were doing. The big character-exposition scene involving the doctors is numbingly repetitive, and seems to go on for days. A handful of scenes intended to justify that kiss in the final shot feel as though they were filmed as afterthoughts and then wedged into the movie wherever they could be made to fit. What suspense there is by the final reel is generated not by any respectable means, but by the dishonest expedient of a misleading title: the movie’s called Doctor X, the villain is a doctor, and there is also a doctor involved whose last name starts with an “X,” but the suspect thereby designated ends up having nothing whatsoever to do with the crimes. Then there’s the extraordinary ambivalence that the filmmakers display toward their scare tactics. On the one hand, there’s a lot of the usual “spooky old house” crap, with lots of skeletons and taxidermized animals and menacing butlers popping up all over the place, and most of that stuff is basically played for laughs. But at the same time, we’ve got this lunatic running around strangling and eating people, and somehow it’s all tied into his incomprehensible research into the creation of “synthetic flesh”— itself an awfully ghoulish concept by 30’s standards.

There is an upside, though. The climactic scene really is awfully good, at least until Taylor shows up to save the day, and the makeup effects for Dr. Wells’s false face are quite well realized. The biggest and most pleasant surprise comes from Fay Wray, though, who demonstrates that she really could act, if only anyone would bother to write her a part with some worthwhile dialogue. It’s almost worth having to put up with Lee Tracy’s clownish and stereotyped performance as the reporter for the several scenes in which Wray’s quick-witted, sharp-tongued character cuts him down to size. It’s also fascinating to compare this movie with the following year’s The Mystery of the Wax Museum, uncharacteristically released directly under the Warner Brothers label. Warner would hire virtually the entire cast of Doctor X back to work on that movie, which like this one involves a madman with a false face, human bodies put to uses their original owners would surely not approve of, and a fast-talking comic relief reporter in an entirely too-central role. Both films also used two-strip Technicolor in their initial release, and both include the embarrassing spectacle of living extras pretending to be wax dummies. Of the two films, Doctor X is by far the less skillfully crafted, but it is also a bit more enjoyable to watch due to its harder-hitting scare scenes and uncommonly grisly premise. My instinct is to read that extra aggressiveness as a hangover from the days of First National’s independence; at the very least, I’ve consistently found the horror movies Warner released through First National to be just a little bit edgier than those they circulated under their own name, despite the relative unprofessionalism that accompanied the B-unit’s lower budgets and tighter shooting schedules.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact