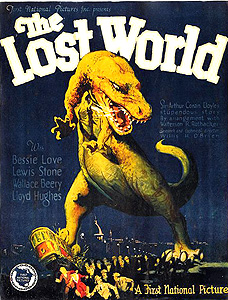

The Lost World (1925) **˝

The Lost World (1925) **˝

To me, one of the most fascinating facts of early movie history is that virtually every form of trick cinematography in use today had already been developed, in principle if not in specific technique, by about 1915. Most species of sleight-of-camera— double exposure, forced perspective, matte composition, and a host of others— were the brainchildren of French fantasist Georges Melies, but the technique of stop-motion animation rather quickly became identified with the name of a different cinematic pioneer, the American Willis O’Brien.

In the beginning, the similarity between the two men’s careers was greater than it might appear today, for though O’Brien is best remembered for his feature films, he got his start with precisely the sort of spectacle-driven shorts that made Melies famous. These were not narrative films of the sort to which we are now accustomed; even when there was a story being told (as in Melies’s A Trip to the Moon), that story was used solely as a flimsy framework on which to hang the fantastic and seemingly impossible images that were the film’s real reason for being. This approach to moviemaking, which film historian Tom Gunning has dubbed “the cinema of attractions,” was in fact the dominant one during the first decade and a half of the 20th century, as seems more or less inevitable given the technology of the time. After all, with running times generally limited to ten minutes or less, there was precious little room for plot or theme or characterization in the typical motion picture circa 1905. Beyond that, audiences that wanted to see a play could always go to the stage theater, so what most directors focused on in those days was using their new medium to create images of a sort that only film could deliver. O’Brien’s early shorts, like The Dinosaur and the Missing Link and The Ghost of Slumber Mountain, fit neatly within this tradition, featuring the barest skeleton of a story, which served only to set up an excuse for the captivating scenes of battling prehistoric beasts that got the tickets sold and the seats filled in the first place. And even after the movies began to compete directly with the stage by dealing in stories worthy of the name, the cinema of attractions still held powerful sway. Perhaps the starkest illustration of this point is O’Brien’s first feature-length production, First National’s The Lost World. The Lost World was, in fact, the first feature film to make extensive use of stop-motion, period; O’Brien got the job because his name was virtually synonymous with the technique, and had proven value as an audience draw. The Lost World is also something very much like The Ghost of Slumber Mountain writ large. Despite being nominally an adaptation of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s novel of the same name (and beginning with a brief introduction by the author as a sort of public endorsement), it is really little more than a spectacle short on the Melies model, but with a running time bloated out to almost two hours.

Newspaper reporter Edward Malone (Lloyd Hughes, from The Drums of Jeopardy and the 1929 version of The Mysterious Island) has a problem on his hands. His girlfriend, Gladys (Alma Bennett), has figured out that he’s a great big wimp, and she refuses to marry any man who has never looked death in the face on some grand and heroic adventure. Needless to say, adventures— even of the petite and mundane variety— are in rather short supply in 1920’s London, and Malone is entirely at a loss for an answer to his fiancee’s challenge.

Fortunately for him, working at the offices of the London Record-Journal means that he’ll be among the first to hear about it in the event that an adventure should happen to breeze into town. And as a matter of fact, an adventure is about to do just that in the form of the aptly named Professor Challenger (Wallace Beery). Challenger is a biologist of the maverick stripe that always seems to show up in tales of this sort, and the reason for his current state of disfavor among his more conservative colleagues is what he claims to have seen on his last expedition into the jungles of the Amazon basin. If Challenger is to be believed, somewhere up one of the great river’s forgotten tributaries is a plateau ringed by cliffs 150 feet high, the interior of which is home to a thriving population of dinosaurs! Most listeners are disinclined to believe him, however, for the only evidence he has to back up his extraordinary assertion is a handful of blurry, water-damaged photographs which, in their present condition, could plausibly be said to depict just about anything. And since none of Challenger’s companions on this mission returned alive, he doesn’t even have any witnesses to corroborate the fantastic yarn. Edward hears all this when he surreptitiously covers the story of Challenger’s return for his newspaper (surreptitiously, because the professor has explicitly banned all reporters from the lecture hall for the night of his presentation to the Royal Scientific Society), and he stands up to volunteer when Challenger asks if anyone among his audience is willing to accompany him back to Brazil to document the discovery in a more acceptable manner. That should do nicely for “looking death in the face,” don’t you think? Challenger refuses to have him at first (Malone stupidly admitted that he was a reporter when the professor asked him what he did for a living), but he comes around when he hears that the Record-Journal might be persuaded to fund the expedition if it were presented as a rescue mission for celebrated explorer Maple White, who was separated from Challenger on his previous venture, and whose fate remains unknown. With the newspaper footing the bill, Challenger sets off some weeks later, together with Malone, White’s daughter Paula (Bessie Love), big game hunter Sir John Roxton (Lewis Stone, later seen in The Mask of Fu Manchu and 1937’s remake of The Thirteenth Chair), and coleopterist Professor Summerlee (Arthur Hoyt), the latter of whom views the whole business as the perfect opportunity to expose Challenger for a shyster and a scam artist.

Summerlee’s wrong, of course. There is indeed a cliff-ringed plateau, and there are indeed dinosaurs. There’s also some sort of protohuman, who spends the entire duration of the Brits’ venture on the plateau skulking along behind them in company with a chimpanzee. No, I’m afraid I don’t understand that last part, either. In any case, the whole of the plot for the next hour or so consists of the following five events: A Brontosaurus dislodges the tree trunk the explorers had used as a bridge between the sheer-sided plateau and the rather more scalable pinnacle of rock beside it, cutting off their only route back to the outside world. Edward Malone and Paula White fall in love, neatly removing Malone’s entire reason for coming on the trip. Roxton finds a skeleton wearing a locket containing Paula’s portrait and inscribed with the monogram “MW.” And the volcano at the center of the plateau erupts, imparting a certain urgency to the efforts of the two porters encamped at the foot of the plateau to fabricate a rope ladder whereby the explorers might escape. When it comes, said escape attempt will be facilitated by Challenger’s pet, Jocko the Plot-Point Monkey, and opposed by that sneaky Australopithecine, who was beginning to look like he never would have anything to do with the story. Apart from all that, it’s just dinosaurs, dinosaurs, dinosaurs, one of which— another Brontosaurus— eventually makes its own contribution to the plot by falling from the edge of the plateau into a prodigious mud-pit below.

That dinosaur’s sacrifice is truly a heroic one, too, for it gets us to the best and most memorable part of the film. The Brontosaurus, though badly injured, is still alive when Challenger and company escape from the lava flows, and the professor makes history as the first movie character ever to mistake the transportation of a prehistoric monster to a civilized population center for a good idea. When he and his companions ship out for England about a month later, it is with the dinosaur caged in the hold, and you can just imagine Challenger gloating the whole way home about the looks he’s going to see on the other scientists’ faces when he presents them with a real, live sauropod. That’s not quite how it turns out in practice, though. There is an accident at the dockside with the machinery that hoists such heavy loads out of the holds of ships, and the dinosaur bursts out of its damaged cage to make a tremendous nuisance of itself in downtown London. The Brontosaurus is understandably none too impressed with the Bobbies and their billyclubs, and it is only through the animal’s own unfamiliarity with urban living that the city is spared truly large-scale destruction. Evidently the engineers of the Tower Bridge never anticipated that it would be asked to bear so massive a weight concentrated through the relatively tiny area of a sauropod’s four feet, and the landmark’s center span collapses, dumping the monster into the Thames, whence it swims out to sea, never to be heard from again save through a few scattered reports of sea-serpent sightings.

You will note the considerable resemblance between the above plotline and that of O’Brien’s subsequent King Kong— intrepid explorers penetrate unknown territory, fight gigantic monsters, and foolishly bring one home with them when they return to civilization. The difference between the two movies that makes King Kong a classic while The Lost World remains a mere curiosity is that the makers of the former film did a much better job of integrating narrative and spectacle than did those of the latter. In fact, so divorced are the story elements of The Lost World from the special effects sequences that it was possible for Warner Brothers (who acquired First National and The Lost World along with it in 1928) to reissue this movie as a supporting feature, with its running time shaved down to a mere 62 minutes— almost all of it dinosaur footage. (Indeed, up until just a few years ago, this drastically edited version was the only one available.) Even with the human story reduced to “six men and a woman go to the jungle and bring home a Brontosaurus,” the movie more or less made sense. To say that a film is put together such that it is reasonably forgiving of cutting on so vast a scale is in no sense a form of praise, nor is it a positive commentary to note that a viewer who finds himself bored with one side of The Lost World or the other can safely pass the time between “good parts” with other activities, secure in the knowledge that nothing he has missed will have any bearing on what he’s waiting around to see. The fact that Warners cut what they did when they had the chance also shows that they knew enough to recognize the cinema of attractions when they saw it.

Which brings me back to Willis O’Brien, and to the reason why those few of us who do so still remember this movie. I’ve already said that The Lost World is no King Kong, and that’s true even from the narrow perspective of a stop-motion enthusiast. Part of the problem may be the difference in film-speed standards between the sound and silent eras. Sound films are projected at a rate of 24 frames per second, while silents generally ran significantly slower— as little as 16 fps in the earliest days. (This, incidentally, is why modern-day presentations of silent movies often have that strange frenetic quality about them. They look like they’re running too fast because they are.) Frame rate would obviously bear directly on the fluidity of any form of animation, and that difference may be a contributing factor to the extreme jerkiness we see so much of here, but that’s obviously not the full explanation. I say that because, while most of the dinosaur scenes are so jumpy they look more like a montage of stills than real animation, everything involving the Brontosaurus is much, much better. The climactic attack on London is almost as good as its more famous counterpart from eight years later, even if the dinosaur lacks Kong’s charisma. I wonder if what we’re really seeing here is an attempt by First National to hedge their bets. Remember, this isn’t one of the top Hollywood studios we’re dealing with, although First National was fairly important at the time. Remember also that no feature-length film like The Lost World had ever been attempted before 1925, and that the producers were taking a real gamble in releasing this one. Given the labor-intensive and therefore inherently expensive nature of stop-motion animation, it may be that O’Brien was operating under instructions to cut corners in the “lesser” set-pieces, saving his time and energy for the big London rampage, which is what most viewers were going to leave the theater remembering most vividly anyway. In any case, First National’s gamble did indeed pay off. The Lost World was a success, and the studio would engage O’Brien at least twice more over the course of the decade. (Although it’s worth pointing out that no subsequent O’Brien project for First National ever made it anywhere near completion.) For us today, the matter is a simple one: The Lost World is a vital piece of monster movie history. The extent to which that matters to you is also the extent to which you should seek out a chance to give it a look.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact