The Drums of Jeopardy/Mark of Terror (1931) **

The Drums of Jeopardy/Mark of Terror (1931) **

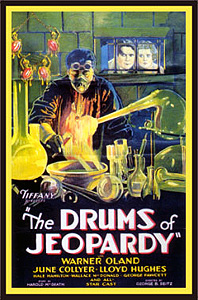

When Universal scored big with Dracula in February of 1931, other studios were quick to perceive that there was money to be made in the fright business, but by no means were all of them so fast to spot the thing that made Dracula different from any previous American horror film. Paramount got the hint early, as did the Halperin brothers, but most of the other production companies in Hollywood continued to focus on purely human horrors, rather than taking up Universal’s supernaturalist innovations, until after the wave had crested in 1933. Tiffany’s The Drums of Jeopardy is an interesting example of Poverty Row’s first-generation horror talkies. Like many films of its era, it was a remake of a profitable silent, and in what would become a common Poverty Row ploy, it casts as its main villain an actor whom the majors generally relegated to character parts. And although it makes one token gesture early on toward creating a Universal-like atmosphere of gothic morbidity, it quickly abandons the experiment in favor of more familiar mad genius and spooky house tropes. Even in 1931, The Drums of Jeopardy probably looked pretty old-fashioned.

The second-tier actor getting the star treatment here is Warner Oland, whose highest-profile gigs for the majors to date had been the title roles in Paramount’s The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu and The Return of Dr. Fu Manchu. That’s surely no coincidence, for apart from the villain being Russian instead of Chinese, The Drums of Jeopardy might as well be a Fu Manchu movie itself. See if this bad-guy origin story sounds at all familiar. Anya Karlova (Florence Lake) is in a bad way. She attempted suicide a few hours ago, and while she may not have enjoyed instant success, it’s plain enough that the girl is on her way out; maybe she took some slow-acting poison. In response to the developing tragedy, the family maid has dispatched Peter (Misha Auer, of The Monster Walks and Condemned to Live), another servant whose specific function is not quite clear, with an explanatory note to give to Anya’s father, Boris. Yes, that’s right— Boris Karlov. Incredible though this may seem, that was actually the character’s name in the novel from which The Drums of Jeopardy ultimately derives, leaving us with an intriguing, if minor, mystery. William Henry Pratt’s first screen credit as Boris Karloff was for 1920’s The Deadlier Sex, released not quite three months after the Saturday Evening Post began its serial publication of The Drums of Jeopardy, but he had been acting onstage in Ontario since 1909. Reports conflict as to exactly when Pratt adopted his famous pseudonym, however, so it remains unclear whether we’re looking at a strange coincidence or an act of conscious emulation on Karloff’s part— although we probably can rule out the possibility of author Harold MacGrath naming his villain after an obscure Anglo-Canadian stage actor. Anyway, the maid’s message reveals that Anya had learned that she was pregnant, and that it was the attendant shame that led her to take her own life. Anya refuses to reveal the man’s identity, however, least of all to her enraged father. Still, Boris gets a pretty good idea when he finds, hidden under his daughter’s pillow, a necklace that he recognizes as an heirloom of the princely Petroff family, the famous Drums of Jeopardy. It may not offer quite the specificity of a love letter, but it certainly narrows down the list of possible suspects.

At that very moment, old General Petroff (George Fawcett) is throwing a dinner party, and he was just telling his guests the story of the priceless necklace. It’s of Indian origin, brought back by the general’s great-grandfather from one of his military campaigns, and legend has it that there’s a dormant curse attached to it. The chain bears four gold-and-ruby pendants, in the form of fakirs playing drums, and the story goes that if someone detaches a pendant, anyone they give it to is doomed to die. One of the guests asks if she could see the necklace, so Petroff tells his grandson, Gregor (Wallace MacDonald), to go fetch it from the safe. Gregor claims to have forgotten the combination, but something tells me he really remembers it very well indeed. The young man won’t keep his chicanery with the family jewels hidden that easily, though, for the general merely sends his other grandson, Nicholas (Lloyd Hughes, from A Face in the Fog and The Mysterious Island), in Gregor’s place. Nicholas— to say nothing of the general and his son, Ivan (The Soul of a Monster’s Ernest Hilliard)— is most alarmed to see the safe empty, but the Petroffs and their guests are about to have a more pressing disturbance yet to contend with. No sooner has the disappearance of the Drums of Jeopardy come to light than Anya Karlova (barefoot and dressed only in her nightgown despite the cold of a Russian winter’s night) bursts in through the French doors from the veranda to warn her lover of his danger. Gregor is just lucky the cold finishes what the poison (or whatever it was) had started before Anya is able to reach him, for Boris is in hot pursuit of his daughter. Karlov leaves the Petroffs unmolested for the moment, but vows his revenge upon whichever one of them it was who brought Anya to her ignominious end.

That was all before the Revolution. Russia having become a very bad place to hold a noble title in the years since, the Petroff family has moved steadily westward, driven by the knowledge that Karlov, now a man of some importance among the Bolsheviks, has all the resources he could possibly need to find them and trap them if ever they settled down in one place. Even so, Karlov and his agents have kept sufficiently close tabs on the Petroffs to corner and kill the old general. In desperation, Ivan has made contact with the United States government, seeking political asylum. Martin Kent (The Most Dangerous Game’s Hale Hamilton), of the Secret Service, has been assigned to the case, and he makes clandestine arrangements to bring the Petroffs across to New York City. Kent’s efforts at secrecy are no match for Karlov’s spies, however, and the fugitives nearly fall into their enemy’s hands at the very dockside. Ivan, Nicholas, and Gregor slip out of the trap, but it’s clear enough that simply fleeing to America will not suffice to keep them from harm. Ivan did just receive a note from Karlov containing one of the accursed pendants from the Drums of Jeopardy, after all, just as his father did before him.

The Petroffs face another attempt on their lives immediately upon their arrival in New York. The three fugitives become separated while dodging the assassins, and Nicholas is injured by one of Karlov’s men. Bleeding badly from a headwound, he nevertheless loses his pursuers by scaling an apartment block’s fire escape, and letting himself in through a penthouse window. This puts Nicholas in the bedroom of Kitty Conover (June Collyer, from Murder by Television and The Ghost Walks), a feisty American girl such as his late mother had been. Kitty keeps a pistol in her nightstand, and while she’s willing to cooperate when the obviously injured stranger begs her to phone Martin Kent, she keeps Nicholas covered the entire time. Nicholas passes out while talking to Kent, and breaks the telephone handset when he hits the floor; Kitty is thus forced to send her blustery old aunt, Abbie Krantz (Pillow of Death’s Clara Blandick), out to fetch him a doctor, rather than summoning one the easy way. Naturally, the first person Abbie asks for assistance out on the street is Karlov’s henchman, Peter, who immediately draws the appropriate conclusions from her strange and somewhat muddled story. The doctor he brings to the apartment is none other than Boris Karlov (who really is a chemist or a pharmacist or something, so Peter isn’t exactly lying when he introduces Kitty and Abbie to his boss). Luck is with Nicholas again, however, for Kent arrives on the scene only minutes later, and the Russians find themselves too busy fighting their way out of Kitty’s penthouse to worry much about accomplishing their real mission.

Obviously, what the Petroffs need at this point is a safehouse, and Kitty magnanimously suggests her family’s country manor upstate. Kent is somewhat reluctant to involve Kitty and her aunt, but an offer like that is difficult to refuse under the present circumstances. The trick will be to prevent Karlov from uncovering the hideout— and since Kent lays out the plan within earshot of the skulking Peter, that game is pretty well lost before it’s even begun. The remainder of the movie detours pretty far into traditional spooky house territory before getting back to its Sax Rohmer-ish business, and facing the Petroffs and their American allies with a succession of deathtraps that would make any Republic serial villain smile.

If you’re among the vast majority of even old-timey horror fans who have never seen The Drums of Jeopardy, you may rest assured that you aren’t missing very much, although the movie certainly does get off to a strong start. For one thing, it is remarkably frank about the sexual shenanigans that set the plot in motion, even to the extent of having the forbidden word, “pregnant,” peeking down from above the frame in the close-up when Karlov reads the maid’s note. (Production Code? Ha! The Drums of Jeopardy has your Production Code right here.) There’s also a great double misdirect in our introduction to Boris Karlov. We first see him toiling away in the classic mad lab he has set up in the dungeon-like basement of his dacha, but then the scene shifts gears to reveal him as a concerned and loving father, instead of the evil genius we’re expecting. Of course, Karlov really will be embarking on a career as an evil genius by the time the next scene wraps up, proving the audience’s knee-jerk assumptions about him correct after all. And of perhaps the greatest importance, the whole first half is so stuffed full of action that there isn’t a spare moment in which to register the presence of all the usual forms of early-30’s creakiness. They’re all there, you understand, but chances are you’ll be too busy trying to keep abreast of an hour’s worth of plot squeezed into perhaps half that much time to pay them any mind. But then the setting shifts to the Conover estate, and The Drums of Jeopardy collapses, wheezing and clutching its chest, into the usual rut. Lights go out, windows blow open in the wind, women scream at nothing in particular, wounded men fall through doorways and expire dramatically after delivering one last, portentous line, and through it all, Karlov and Kent keep finding excuses to make speeches at each other. The central gimmick of the “curse-bearing” necklace gets short shrift indeed after the change of venue, leaving you to wonder why the filmmakers ever made such a big fuss about it in the first place. Suspense is generated primarily by expository cheats, and the cheating goes on right in front of the audience’s faces. Only during the last few minutes does The Drums of Jeopardy regain its footing, with a climax that tries— albeit with notably imperfect success— to remind you of what had been so appealing about the early sections of the film. Until that point, about the best thing I can say for the second half of The Drums of Jeopardy is that it actually wrings a certain amount of payoff out of the odious comic relief.

Thanks to Liz Kingsley for furnishing me with a copy of this film.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact