The Mysterious Island (1929) ***

The Mysterious Island (1929) ***

In his introduction to the latest Signet paperback edition of The Mysterious Island, Bruce Sterling posits that the key to the novel’s greatness lies in its freedom from the constraints of geography, in the biological and ethnological senses of that term as well as the physical. Unlike, for example, Five Weeks in a Balloon or Around the World in 80 Days, or so Sterling says, the premise of The Mysterious Island liberated Verne from his self-imposed tyranny of realism, permitting his imagination to run wild in whatever direction he saw fit. This is an interesting point, and bears returning to frequently as one reads the book, and encounters the fruits of that free-range imagination. For who, having once experienced it, can forget the pulse-pounding thrill of the grouse-hunting scene? The nail-biting tension of the latitude fixation scene? The epic triumph of the egg-roasting scene? Hard indeed is the heart that is not moved by such mellifluous dialogue as:

“Do you know the first principles of geometry?” he asked. “Slightly, captain,” replied Herbert, who did not wish to put himself forward. “You remember what are the properties of two similar triangles?” “Yes,” replied Herbert; “their homologous sides are proportionate.” |

One can only conclude that Sterling possesses a highly developed sense of irony. Despite what he says to the contrary, The Mysterious Island enters the country of “pure fantasy” only during its occasional descents into the utterly preposterous, as when Cyrus Harding, the chief of Verne’s five Robinson Crusoids, astoundingly succeeds in producing some six liters of nitroglycerine from the body fat of a slain dugong. (It might also qualify as an indulgence in pure fantasy to maroon a young boy in the middle of the South Pacific with four older men, and yet not have his pubescent ass immediately become the most sought-after commodity on the island once the necessities of life were fully seen to, but polite authors didn’t write about that sort of thing in 1874.) Otherwise, The Mysterious Island is as stultifyingly schoolmarmish as any work of fiction ever composed, and by the time it finally gets around to revealing itself as a sequel to the only slightly less tedious 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, the damage has long since been done. It is thus small wonder that the makers of the best known film adaptation, Charles Schneer’s 1961 version for Columbia, felt compelled to dress the story up with both a sexy girl and a menagerie of Ray Harryhausen monsters. But just as Columbia was not the first Hollywood studio to bring The Mysterious Island to the screen, neither were they the first to do so by garbling the story (actually, “improving” might be closer to the mark) beyond hope of more than the faintest recognition. In fact, in the case of MGM’s version from 1929, even faint recognition is highly unlikely.

Far from Richmond during the climax of the American Civil War, this Mysterious Island begins in the imaginary kingdom of Hetvia, during no definite period of human history whatsoever. Certain plot points can be taken to imply a physical setting somewhere along the coast of the Baltic Sea and a temporal setting sometime between the publication of The Communist Manifesto and the appearance of the first practicable self-propelled submarines in the mid-1880’s, but that’s as close as we’re going to get. Hetvia is a bitter land, ruled by a despotic king and wracked by peasant uprisings and palace coups. Just off its coast, however, is a mysterious island (called, imaginatively enough, Mysterious Island— although at no point do we ever see any indication of what’s supposed to be mysterious about it) governed by the self-exiled nobleman scientist Count Andre Dakkar (Lionel Barrymore, from The Devil Doll and Mark of the Vampire). Dakkar is as benevolent as the king is tyrannical, and the political system of his island is fiercely egalitarian in content, if not always in form. (Dakkar has not renounced his title, after all, nor divvied up ownership of his lands among the peasants who work them.) But rather than serving as a hotbed of revolutionary fervor, Mysterious Island is instead a haven for introverted intellectuals who simply want to be left alone to pursue their studies. Consequently, it is rather inconvenient that Dakkar’s closest friend on the mainland, Baron Hubert Falon (Montagu Love, of The Cat Creeps and The Haunted House), happens to be preparing to usurp Hetvia’s throne. Falon wants Dakkar’s backing, but the count cares nothing for politics. All he’s interested in is the unusual convection current that flows through the volcanic chimney at the center of his island, bringing with it curious objects from the deepest part of the sea. As Andre explains to his increasingly inattentive friend, that current has put him in possession of a set of bone fragments which appear to have come from a humanoid creature currently unknown to science, and it is Dakkar’s belief that the depths of the sea harbor a race of intelligent beings who are the forgotten cousins of mankind. Falon gives him the old, “That’s an interesting theory— but you’ll never be able to prove it,” routine, to which Dakkar responds by saying that the workers in his shipyard are currently busy on the construction of a vessel capable of traveling to the ocean’s floor and back. That, finally, gets the baron’s undivided attention. Especially once Dakkar mentions that his submarine will carry weapons with which to defend itself against whatever dangers it may encounter in the abyss, Falon latches onto his friend’s project as the ultimate means of seizing and consolidating power over Hetvia, having little patience for Andre’s contention that the wondrous vessel is meant for exploratory purposes only.

Falon manages his revolution even without a submarine, but that doesn’t mean he loses interest in the military potential of the exotic ship. As Diving Ship 1 nears completion, the new king drops in on Mysterious Island to observe the vessel’s trials. In doing so, he incidentally demonstrates first that he lusts after Dakkar’s sister, Sonia (Jacqueline Gadsden, who appeared alongside Barrymore previously in West of Zanzibar and The Thirteenth Hour), and second that his fusty sensibilities are shocked by the girl’s romantic interest in the count’s low-born chief engineer, Nikolai Roget (Lloyd Hughes, from The Lost World and A Face in the Fog). (Dakkar, putting his money where his egalitarian mouth is, openly encourages the pairing.) Falon’s ulterior motive for the visit becomes apparent once Nikolai and the sub are safely out at sea; while everyone on the island is following Diving Ship 1’s trials, a regiment of Falon’s hussars overruns Dakkar’s stronghold, killing the workers indiscriminately and taking the count and his sister prisoner. This betrayal avails Falon little, however, for Sonia’s last act before being arrested is to hide all of the papers relating to the development and construction of the submarines. Thus not only does the usurper not get what he came for, he can’t even torture the desired information out of Count Dakkar. And even when he thinks to try torturing Sonia instead, she holds out long enough to go into shock rather than reveal a single thing to her captor.

Nikolai, meanwhile, has figured out that something is desperately amiss back home, and he keeps the submarine prowling the waters around Mysterious Island awaiting an opening to counterattack. At the earliest opportunity, he and his men stage a daring raid on the island to rescue Count Dakkar, but he is unable to locate Sonia that first time around. Then he and Dakkar receive a transmission from Sonia on the ship’s underwater radio, informing them that she has escaped, and will meet them on a rocky promontory at midnight. It’s all a trap, however. That voice on the radio was not Sonia, but rather another female captive impersonating her under threat of torture. And while Sonia is out on the rocks come midnight, she’s tied to them, and the high ground overlooking the cape is bristling with Falon’s artillery. Diving Ship 1 gets blown to shit the moment it surfaces, and the crippled sub embarks on a voyage to the ocean floor under circumstances rather different from those its creator had originally envisioned.

Falon hasn’t won yet, though. Leaving aside the fact that he still doesn’t have his hands on the secrets of creating or even operating Dakkar’s diving ships, he’s about to lose even the one realistic means by which he might gain those secrets. Among the residents of Mysterious Island who survived the usurper’s initial onslaught is Mikhail (Harry Gribbon, from the first talkie version of The Gorilla), the foreman of the shipyard, and he’s not at all happy about the recent change of management. Mikhail sneaks out onto the rocks while Falon is engrossed in watching Diving Ship 1 sink, and he not only unties Sonia, but leads her down to the shipyard, where Diving Ship 2 lies at anchor with its crew aboard. Mikhail fights his way through the soldiers guarding the ship, and makes so much headway in organizing the crew to get the vessel underway that Falon and his flunkies accomplish little but to get themselves trapped inside when they rush aboard in response to the commotion. Mikhail is killed in the ensuing fighting, but Sonia is resourceful enough to turn the tables on Falon all by herself. Reasoning that the game is up for her either way, Sonia tosses a hand grenade at Diving Ship 2’s air compressor, destroying it completely. Without the compressor, there’s no way to blow the sub’s ballast tanks, and thus no way to return to the surface, arrest the dive, or even adjust the sub’s trim so that it sinks on an even keel.

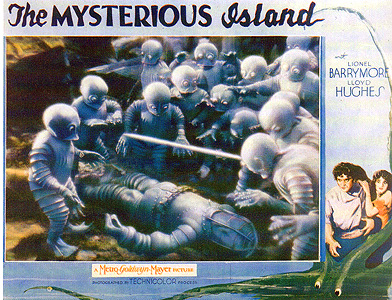

So what, then, do you suppose the two vessels are sinking toward? You remember that curious skeleton Dakkar had assembled from bits and pieces brought up by the convection current in the volcano? Well true to the count’s speculations, those bones came from an intelligent marine humanoid, and not only does a population of the strange creatures still exist, they’ve built an entire city on the seafloor. The Sea People also don’t want the company, and as if the surface-dwellers didn’t already have enough problems stemming from their internecine conflict and their crippled submarines, they now have thousands of angry, armed gill-midgets to contend with, to say nothing of the Sea People’s pet giant octopus or the huge sea-dragon that also inhabits the area.

Attentive viewers who are well-versed in Jules Verne’s writing will notice something very interesting about The Mysterious Island. Though it has nothing in the world to do with the novel from which it takes its name, it ties in very strongly with another of Verne’s books. In 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Verne tells us relatively little about Captain Nemo, beyond that he is a brilliant scientist who is altogether fed up with the human race. Verne had a more developed origin in mind for him— something about being a Polish nobleman driven to misanthropy by the despotism of the czar— but was advised to drop it by his editor. When the character resurfaced four years later in The Mysterious Island, his story was finally told, but it had changed rather drastically during its extended incubation. Perhaps because France and Russia were moving tentatively toward an alliance by 1874, while the traditional cross-channel rivalry with Britain was heating up again after the relaxation of hostilities that accompanied the Crimean War, Nemo’s country of origin had shifted from Poland to India, and it was now British imperialism from which he had made his retreat beneath the waves. It was also revealed that Nemo’s real name was Dakkar. You see where I’m going with this, right? Hetvia looks to be not too far away from Poland; Andre Dakkar starts off as an idealistic scientist who wants nothing to do with politics provided that he and his people are left alone to live as they will, but gradually becomes a fierce and bitter opponent of tyranny; Dakkar’s greatest invention is a miraculously advanced submarine, and the last we see of him comes when, apparently mortally wounded, he sails off alone in the repaired Diving Ship 2. Sound at all to you like rather than filming a sequel to 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea according to the plan of the novel, the makers of The Mysterious Island have given us a prequel instead? Hell, the models used to depict Dakkar’s subs even more or less match Verne’s description of the Nautilus!

Acquiring the film rights to a prestigious story, merely to toss that story away en route to the final cut, is not the only modern-day big-studio behavior of which The Mysterious Island stands as a precocious early example. Its production was also a classic Hollywood clusterfuck in the grand style. Audiences who are acquainted with the movies of the 1920’s will likely be taken aback by how little The Mysterious Island feels like a film from 1929, and in fact the first steps toward its creation were taken three years earlier. MGM’s leadership had been impressed by First National’s success with The Lost World in 1925, and they decided they needed a big and impressive sci-fi movie of their own. In an utterly characteristic case of major-studio overkill, the producers laid plans for a three-hour epic, packed to the gills with state-of-the-art underwater cinematography and presented entirely in the recently introduced and hugely expensive two-strip Technicolor process. The studio hired respected French expatriate director Maurice Tourneur (father of the even more respected Jacques Tourneur) to handle the main body of the film, with the underwater scenes going to J. Ernest Williamson, who in those days was the biggest name in the business of aquatic cinematography. Tourneur would do his work in L.A., while Williamson went down to the Bahamas to take advantage of the local seawater’s unrivalled clarity. Of course, since the bosses hadn’t settled on a finished script yet, all that preparation was just a wee bit premature. The rewrites and re-rewrites and re-re-rewrites took months, and by the time the producers thought they were happy, it was hurricane season in the Caribbean. Undaunted, MGM set Williamson to work, with the result that he and his team got clobbered by no fewer than three hurricanes, leaving them with nothing to show for their labors but a humongous heap of the world’s most advanced amphibious rubble. By the time the rebuilding was completed (and you better believe that cost a pretty penny), the script had changed yet again into something completely unrecognizable. Williamson soldiered on in the face of this setback, too, but he might as well not have bothered. Only a few minutes of his footage made it into the completed film.

But that’s all second-unit stuff, right? Surely the producers were running a tighter ship back home? Ha. For one thing, there was the additional round of rewrites that made Williamson’s job that much harder over in the Bahamas. For another, Maurice Tourner proved to be one of the world’s great masters of dicking around, and he was none too eager to accept directives from upstairs to do things that were contrary to his directorial instincts— like, for example, all those times studio bigwig Irving Thalberg implored him to hurry the fuck up. Eventually, relations became so strained that Tourneur either quit or was fired, to be replaced by another European of lofty repute: Benjamin Christensen, director of Witchcraft Through the Ages. This did not solve the problem. Christensen was just as slow and just as big a pain in the ass as Tourneur had been, and as 1926 rolled over into 1927, there was little indication that The Mysterious Island was ever going to be finished. Finally, the movie was handed over to Lucien Hubbard, who had apparently been responsible for the final version of the screenplay, and who was under contract to the studio, making him unlikely to cause the sort of headaches the two previous directors had given Thalberg. The studio’s original ambitions had to be scaled back considerably in order to do it (a 95-minute running time instead of three hours, underwater scenes shot mostly in a big-ass tank rather than on location, etc.), but Hubbard managed to get The Mysterious Island in the can by the end of 1928.

Of course, there was a whole new set of problems by then— namely, the talkies. 1928 and 1929 comprise an odd transitional period, during which films were being made both with and without sound, and occasionally even with sound in only a few key scenes. Nevertheless, it was perfectly obvious that a prestige picture like The Mysterious Island couldn’t very well be released completely silent, but because all the key decisions regarding its production had been made before the advent of sound, completely silent was just what it was. Thus began a round of re-shoots, which was made even more extensive than it might have been because of the perception on the studio bosses’ parts that the actor originally cast as Baron Falon (Warner Oland, whom we last saw in The Werewolf of London) was unacceptable in a talkie because of his thick Swedish accent. Enter Montagu Love and exit another vast heap of money. Naturally, there was nevertheless a limit to how much could be re-shot, and when The Mysterious Island finally limped wearily into theaters late in 1929, it was in the form of a mostly silent film over which sound effects and crowd murmurings had been dubbed with varying degrees of success, interrupted occasionally by painfully awkward scenes of spoken dialogue which play like they were spliced in from some other movie altogether. The final kick in the ass? After all that work and all those travails, The Mysterious Island tanked, and tanked hard.

And yet— incredibly— in spite of all that, The Mysterious Island turned out to be a remarkably effective film. There are problems, it must be admitted. Nobody except maybe Lionel Atwill could have pulled off Baron Falon with a straight face, and Montagu Love’s performance ranges from cringe-inducing to utterly hilarious; it’s a pity his moustache isn’t long enough to be twirled. Lionel Barrymore, meanwhile, is just bizarre, at least in his talking scenes. The primitive recording equipment demanded a tightly composed frame with no freedom of movement for the actors (and even with the blocking as restricted as it is, there are moments when the microphone can’t quite catch the dialogue), but did that stop Barrymore from playing to the back row? You’re goddamn right, it didn’t! Prevented from waving his arms about and striking dramatic poses! as was his wont, Barrymore instead fidgets constantly, pulling on his chin, scratching the nape of his neck, fiddling with his hair… It’ll make you antsy just to watch him. But what does work about The Mysterious Island works beautifully. Barrymore is more comfortable in his silent scenes, and he plays those very well. The story, despite the endless rewrites, is mostly coherent, and takes quite a few interesting and unexpected turns. Sonia Dakkar is among the most vital heroines you’ll ever see in a movie of this vintage, and Jacqueline Gadsden plays her with aplomb. And from the standpoint of sheer spectacle, there’s little cause for dissatisfaction here. The Mysterious Island is a gorgeous movie (it must have been even more stunning in the original Technicolor), standing head and shoulders above the standard of its time both in production design and in the execution of its special effects. The submarines, though obviously models, are the most hydrodynamically sensible I can recall having seen in a science fiction movie. The Sea People are compellingly odd, unusually well-realized, and most unexpectedly portrayed. What’s more, they are present in astounding numbers (I can only marvel that MGM managed to find so many midgets and dwarves), and theirs is one of the few truly convincing underwater kingdoms in the annals of cinema. The matte shots in which an army of the nasty little gill-midgets advances toward the subs under the protection of their giant (and real) octopus would still have looked respectable in the 60’s, and exhibit an attention to detail that is rare in any era. Even the sea dragon (which enjoys the distinction of being among the first saurian monsters in movie history to be portrayed by a juvenile alligator with a bunch of weird rubber shit glued to its body) looks decent! There are no obvious seams between the living reptile and its various prostheses, and considerable mental effort was obviously devoted to altering its appearance— the deeply humped, sauropod-like back is an especially admirable touch. A flop it may have been, but don’t call The Mysterious Island a failure.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact