West of Zanzibar (1928) ***½

West of Zanzibar (1928) ***½

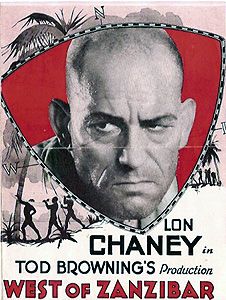

Though there would be no official censorship guidelines in Hollywood until the promulgation of the Production Code in 1930, and no meaningful system of enforcement until 1934, the existence of what would come to be known as the Hays Office stretches well back into the 1920’s. In those earliest days, one of the office’s primary functions was to examine potential source material for movies— novels, plays, short stories, etc.— with an eye toward censorship difficulties, and where appropriate, to designate specific properties as off-limits to cinematic adaptation by the studios. One play that very quickly got slapped with a “do not touch” label by the Hays Office was Kongo, a jungle revenge drama that caused a memorable stir on Broadway during the spring and summer of 1926. You’d have been hard pressed to find a more aggressively sensational offering on the stage in the mid-to-late 20’s, and the potential appeal of a movie version was such that a little thing like an interdict from a powerless censor couldn’t possibly stand in the way. After a suitably obfuscatory name-change— first to South of the Equator, then to West of Zanzibar— Kongo slithered onto the screen in November of 1928 with most if not all of its heralded nastiness intact, and with the box-office draw of Lon Chaney ensuring that lots and lots of people all over the country would be lining up to have their morals corrupted. This was one of the last movies Chaney made under the direction of Tod Browning, and from what I’ve seen, it is among the finest products of that short but fruitful partnership.

This being a Tod Browning movie, Chaney practically has to play some manner of low-rent showman. In this case, he’s a magician called Phroso (note that the clown in Freaks would use the same stage name four years later), who is married to his significantly younger and extremely pretty assistant, Anna (Jacqueline Gadsden, from The Thirteenth Hour and The Mysterious Island). Phroso is still as head-over-heels in love with Anna as he’s ever been, but her attention has been wandering in the direction of a businessman named Crane (Lionel Barrymore, whom Browning would direct again in Mark of the Vampire and The Devil Doll). Crane is preparing to go to Africa to set himself up in the ivory trade, and he plans on taking Anna with him. Anna, of course, has said nothing about this to her husband, and indeed, Phroso doesn’t even realize that he has a competitor for his wife’s affections until the night Crane comes to Anna and tells her to get her stuff together. Anna still can’t bring herself to tell her husband that she’s leaving him for Crane, and so the would-be ivory merchant winds up doing it himself. The confrontation between the cuckold and his rival rapidly turns physical, but the fight is a short one, ending with the magician falling from a backstage catwalk at the theater where he had just performed, breaking his back on impact.

The next time we see Phroso, it’s a year or so later, and he is no longer in the magic business. Indeed, it’s hard to imagine that he’s in any business at all, given the employment prospects for a paraplegic in the late 1920’s. He must have socked away a fair amount of money from his earlier earnings, though, because he doesn’t appear to be living on the street. Nevertheless, Phroso has clearly descended to one of society’s lower rungs, for he is good enough friends with a trio of decaying old bag-ladies for them to let him in on a juicy bit of gossip which pertains to him with extraordinary directness. Anna has come home, and she has brought a baby girl with her. She was last seen headed in the direction of a Catholic church, and Phroso rushes to meet her there the moment he hears the news. He arrives too late, however, for Anna has killed herself right in front of the altar, leaving her infant bawling on the floor beside her corpse. Phroso concludes that her life with Crane in Africa must have been one of unstinting misery, and he vows revenge upon the trader, not only for himself, but for his dead wife as well. And as for Crane’s bastard daughter, Phroso’s hate is more than plentiful enough to leave a super-sized helping for her, too.

Eighteen more years go by, and Phroso has followed his nemesis to Africa. Now known as the bandit chief Dead Legs, Phroso haunts the jungle to the west of Zanzibar, where he has used his illusionist’s talents to install himself as the head witch-doctor of a fierce cannibal tribe. In addition to Chief Bumbu (Curtis Nero, who would return in 1932, when West of Zanzibar was remade as Kongo) and his tribesmen, Phroso’s retinue includes a disgraced doctor (Warner Baxter) and a couple of burly white thugs named Tiny (Roscoe Ward) and Babe (Kalla Pasha). In addition to whatever economic activities normally support the tribe, Dead Legs and his people supplement their income by stealing ivory from the local traders— and one local trader in particular. The raids on Crane’s hunting parties are not carried out by Bumbu’s warriors, however, but by Phroso’s “magic.” Dead Legs sends Tiny out into the jungle in an impressively creepy demon costume; when Crane’s native huntsmen see the disguised Tiny stalking toward them through the jungle, they drop everything and run as fast as their legs can carry them, leaving the ivory to be collected by Bumbu’s men in the morning. Profitable as these ventures are, however, the ivory raids are only the opening gambit in an admirably fiendish plan.

The second phase comes when Phroso dispatches Babe to Zanzibar. In one of the scummiest, most disreputable taverns in the city, there lives a teenage girl named Maizie (Mary Nolan), who has been raised (at Phroso’s instigation) by the proprietress of the establishment as certainly an alcoholic, probably a prostitute, and very possibly a drug addict as well. You got it— she’s Anna’s daughter all grown up, rather too fast for her own good. Maizie knows nothing of her background, though, so it sounds like a dream come true when a gentleman planter arrives at the inn promising to take her to her father. We, however, recognize Babe for what he is; it’s going to take more than a white suit, a trimmed beard, and a fraudulent assertion of teetotaling to fool us. And accustomed though she may be to the rancid underbelly of African colonialism, Maizie is not prepared for the freakshow that greets her at the end of her voyage into the bush. The first thing she sees is Tiny and Doc, both of them blind, stinking drunk and carousing with a pair of native women. The second thing she sees is the transformation of her “gentleman” benefactor into a tattooed lout as repellant as either of the other two men. The third thing she sees is Dead Legs, slithering out into his parlor to meet her with a leer of evil anticipation on his face. And to cap it all off, she’s come just in time to witness a native funeral, and to behold the charming local custom whereby the wife or daughter of the deceased is cast screaming onto the dead man’s pyre. Is it any wonder Maizie tries— with a predictable lack of success— to sneak away during the night?

With Maizie under his roof, Dead Legs can now set in motion the final phase of his plan. He orders Bumbu to send messengers to Crane, informing him that Dead Legs is behind the recurrent ivory heists, and arranging a meeting between the two foes. Then, during the time it takes for Bumbu’s emissaries to deliver the invitation and for Crane to take Dead Legs up on it, the revenge-crazed schemer does everything within his power to dehumanize Maizie even further. He distributes her belongings among the cannibals; he forces her to take her meals on the dining room floor like a dog; he systematically encourages her alcoholism, then forces her into painful withdrawal; it’s even within the bounds of possibility that he permits his native warriors to rape her while foiling her escape attempt. The overarching idea is to present Maizie to her father as a pathetic heap of human wreckage. Then, after revealing the girl’s identity, he will have the natives assassinate Crane— and as the icing on the cake, the tribe’s funerary customs will mean the end for Crane’s long-suffering daughter, too. But unfortunately for Dead Legs, much of his diabolical scheme has been predicated upon a rather serious misunderstanding…

I never thought I’d have occasion to say this about a film from the 1920’s, but West of Zanzibar is one of the most utterly depraved movies I’ve ever seen. It may be relatively demur in terms of onscreen depiction, but the sadism inherent in its story is still shocking almost 80 years later. Even more shocking, its focus throughout is on Phroso. We have here one of the most thoroughly despicable figures in the annals of cinema, and he’s the protagonist of the film! What’s more, his rival manages to seem at least equally odious, for when Crane is let in on what Dead Legs has done, his reaction is not horror or pity at how Phroso has treated Maizie, but mirth at the way in which his enemy’s plot has backfired. Then, as our ostensible good guys, West of Zanzibar gives us a broken-down drunk of a doctor who has willingly allowed himself to be used by the villain for who knows how many years, and the most comprehensively fallen woman the screen would see for many a decade. Much as he had the year before with The Unknown, Tod Browning offers up a movie that explains the whole of the 1930’s Hollywood censorship regime in one neat little package.

The execution this time around is just a little bit less impressive, however. Chaney is as great as ever, slinging his legs around like 70 pounds of unresponsive meat and giving one of the most chilling renditions I’ve seen of a formerly good man hollowed out and poisoned by twenty years of hate. Mary Nolan, too, is perfect. As young and blonde and radiant as any starlet of the studio era, she is nevertheless the farthest thing in the world from an ingenue, with a sneer that could wither a man’s gonads at 50 yards. You get the feeling this girl really could absorb everything the movie throws at her character and still have a fighting chance of pulling herself back together in the end. (The irony there is that Nolan would die very young, the victim of a lifestyle not much less catastrophically debauched than Maizie’s.) The weak links in the chain, as is so often the case, are the insulting portrayal of the natives and the erratic performance of Lionel Barrymore. The former is probably no worse than what you’ll find in any other old jungle movie, but it somehow seems more glaring in comparison to the unexpected modernity of most other aspects of the film. Apart from the lack of dialogue (the soundtrack is limited to background music and the occasional sound effect or crowd murmur) and monochrome cinematography, West of Zanzibar feels like something out of the 1970’s, so the brainless, subhuman Africans really stand out. Barrymore, for his part, is more under control than he ever was in a talking picture, but that isn’t saying a whole lot. He especially bungles the key scene in which Phroso springs Maizie’s identity on him, and we’re supposed to think he’s crying until he throws back his head to reveal that he’s laughing instead. The one could never be mistaken for the other the way Barrymore plays them. But Barrrymore and the cannibals aside, West of Zanzibar is a highly effective film, equal or superior to any peril-in-the-jungle movie I’ve seen.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact