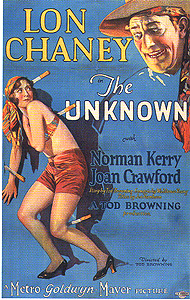

The Unknown (1927) ****

The Unknown (1927) ****

Maybe Tod Browning should simply have stuck to making movies about circus performers. What I’ve seen of Browning’s work from the sound era has been pretty sorry, with one singular, stunning exception: Freaks. I had begun to think that one worthwhile movie was all the man had in him, but I knew I ought to reserve judgement on the subject until I’d had a look at some of Browning’s silent films, which are frequently touted by movie snobs as being among the best of their kind. Well, if The Unknown is any indication, the movie snobs are on to something. Indeed, this incredibly twisted little flick even edges out Freaks in a couple of respects.

The Unknown’s premise is warped, even by Browning’s standards. In Madrid, at an unspecified point in the past, there is a Gypsy circus owned and operated by Antonio Zanzi (Nick De Ruiz). The stars of Zanzi’s circus are his beautiful daughter, Nannon (Joan Crawford, whom we’ll be seeing again at the other end of her career whenever I get around to reviewing Strait-Jacket and Trog), and her partner, Alonzo the knife-thrower (Lon Chaney Sr.). This just wouldn’t be a Tod Browning-Lon Chaney movie, though, if there were nothing physically wrong the central character, and Alonzo’s deformity is a doozey— he has no arms. And yes, my quick-witted readers, that does indeed mean the man throws knives with his feet! So adept is he at this remarkable stunt, in fact, that he is actually able strip Nannon to her underwear by severing the straps of her dress without harming her in any way— quite impressive, any way you look at it. Nannon doesn’t fully realize this, but Alonzo is deeply in love with her, which works out pretty well, when you get right down to it, because Nannon has an odd quirk of her own, in that she is irrationally terrified of men’s hands. In fact, this phobia is the primary obstacle standing in the way of Nannon’s other suitor, the strongman Malabar (Norman Kerry, from the Chaney versions of The Hunchback of Notre Dame and The Phantom of the Opera); the girl actually finds him quite charming, but the moment he tries to touch her, or indeed even puts his hands someplace where Nannon can see them, she gets all queasy and runs away.

You might think Alonzo and Nannon would have a bright future ahead of them, what with the uncanny symmetry between her phobia and his deformity, but there are two factors that militate against this. First, there’s Antonio Zanzi, who doesn’t want his daughter romancing— or, God forbid, marrying— a freak. Zanzi never loses an opportunity to oppose Alonzo’s efforts to win Nannon’s heart and hand, even going so far as to beat the crap out of him with a cane one night when he catches his daughter hanging out in the knife-thrower’s trailer. It takes the intervention of the brawny Malabar to save Alonzo from even worse. The other problem is still more intractable. You see, Alonzo isn’t really a double amputee. He’s merely adopted the persona as a disguise to throw the police off his trail; his true vocations are thief and serial strangler. Now you might think there must be a simpler disguise Alonzo could have chosen— something that didn’t require him to learn how to eat, drink, write, smoke, and throw knives with his feet (and by the way, though the knife-throwing is accomplished by trick photography, Chaney really does perform quite a few more reasonable foot-stunts)— but the wily fugitive has a very good reason for doing things the way he did. Alonzo may not really be armless, but he does have two thumbs on his left hand. Now you see why he’s pretending to have no arms, don’t you? After all, there can’t be that many three-thumbed men running around the Spanish countryside. The two stumbling blocks to Alonzo’s happiness with Nannon threaten to come together one night when Zanzi discovers the knife-thrower’s secret. The boss is out inspecting the circus grounds, and he happens upon Alonzo and his midget sidekick, Cojo (John George, from The Monkey’s Paw and Island of Lost Souls), while the two of them are taking advantage of the late hour to exercise the man’s arms after their many long hours of confinement under the huge leather corset that Alonzo wears under his shirt during the day. Considering that Zanzi’s entire objection to Alonzo’s courtship of Nannon stems from the suitor’s supposed freakishness, you might expect the revelation that Alonzo has arms after all to change the man’s tune, but that’s not how it works. Evidently, Zanzi is so set in his ways that he completely fails to notice that he no longer has any reason to disapprove of Alonzo, and he threatens to tell his hand-phobic daughter that her beloved partner is just as fully equipped with icky, grasping, crustacean-like manual appendages as any other man. Obviously, Alonzo can’t have that, so he pounces on Zanzi and throttles him to death. The catch is that he commits his crime in plain view of the window from Zanzi’s trailer, and Nannon sees him in the act— or at any rate, she sees everything about him but his face, including and especially his distinctive six-fingered hand.

With Zanzi dead, his circus is no more. Apparently, the man died owing huge amounts of money to just about everybody in Spain, and the only way for Nannon to make good on her father’s debts is to sell off the circus’s property. Afterward, she, Alonzo, and Cojo move in together— although I’m not quite sure whether they all rent one big house, or whether they just get a couple of apartments in the same building. Malabar, too, sticks around, though he initially toys with the idea of hitting the road with the rest of Zanzi’s former employees to seek work with another circus. Both men continue their pursuit of Nannon’s affections in the aftermath of the circus’s dissolution, with results that are much as before, at least until Cojo brings to Alonzo’s attention something which he had not previously considered. First, Nannon will inevitably figure out that Alonzo has arms sooner or later in the event that the two of them become romantically involved for real. Alonzo may think the girl will eventually be able to deal with the situation and come to forgive him for his deception, but that still leaves unaddressed the second of Cojo’s points, that Nannon witnessed her father’s murder, and will surely recognize Alonzo’s dual left thumb as the one she saw wrapped around her old man’s throat. Even if she can forgive Alonzo for having hands and keeping them a secret from her, she surely won’t be able to forgive him for slaying her dad!

This is where The Unknown starts to get really weird. Alonzo sees the truth of Cojo’s words, but by this point, he is determined to have Nannon as his wife, whatever the cost. And it just so happens that a certain acquaintance of his from the days of his hardest-core criminality is now a respected surgeon, operating under the name of Dr. Costra (The Return of Chandu’s Frank Lanning). Alonzo sends Costra a letter reminding him of “what happened twenty years ago,” and instructing the doctor to meet him in the operating room of the hospital where he works after closing time on a specific date. Costra naturally figures blackmail is Alonzo’s game, and in a sense, he’s right. But when he asks his former colleague how much money it will take to buy his silence, Alonzo shakes his head and explains that he has something a little different in mind...

Of course, it takes a good long time to convalesce from that kind of surgery, and while Alonzo is out of the picture, he’s missing out on some developments that would be of considerable interest to him. Malabar does not lie idle during the weeks that his rival is away, far from it. Nannon grows terribly lonely with her best friend off on some unexplained errand, and she understandably ends up spending an awful lot of time with Malabar to compensate. In fact, she spends so much time in his company that she gradually overcomes her horror of the male hand and falls in love with him! Thus, when Alonzo finally comes home to Madrid as a real double amputee, he finds that the woman he loves— for whose sake he cut off his fucking arms— has gotten herself another man and ridden herself of the psychological perversity that led him to take such extreme action in the first place! This is going to be a goddamned train wreck, you mark my words.

It’s films like The Unknown that explain where the Hays Code came from. I mean, my God, this is one sick fucking movie, even when looked at through modern eyes. Murder, midgets, crazywomen, polydactyly, elective amputation for the sake of romance— Boxing Helena has nothing on The Unknown. And the best thing about it is that no matter how wacky the events of the story become, everyone involved treats the proceedings with the utmost seriousness, and those in front of the camera have the acting chops to make that serious attitude work. Every time I watch one of Chaney’s silent movies, I find myself flabbergasted at the extent to which his talent towers above that of virtually anyone on the Hollywood scene in the early decades of the sound era. There are two scenes in The Unknown that simply floored me, and in both of them, Chaney plays the central role. The first is the one in which Alonzo pays his visit to Dr. Costra. The segment that has Alonzo detailing exactly what he wants the doctor to do for him plays without a single intertitle— the entire grisly meaning of Alonzo’s explanation is conveyed by the gestures the knife-thrower uses to punctuate his spiel, and by the look of escalating horror on Costra’s face. Alonzo’s demeanor, meanwhile, is chillingly reasonable; he’s thought this thing through quite thoroughly, and he knows exactly what he wants. The subsequent scene in which Alonzo learns about Nannon’s intention to marry Malabar might be even better. As the girl describes how Malabar helped her conquer her lifelong phobia, a smile slowly twitches to life on Alonzo’s face. Nannon and her fiance think the knife-thrower is smiling because he’s happy for them, but we in the audience know better. And when Alonzo’s ensuing laughter grows from a spasmodic chuckle to a debilitating, maniacal guffaw, Nannon’s statement that “He’s laughing at the way everything has happened,” though correct in the strict sense, doesn’t come close to expressing the full truth of the situation. I’ve been known to do some incredibly stupid things for the sake of a woman’s love on occasion, and it wasn’t too much of a stretch for me to imagine what would have been going through Alonzo’s head.

The Unknown isn’t an easy movie to come by these days. It was believed lost for many years, and even after it resurfaced, it didn’t exactly see major circulation. After all, there isn’t much market for silent movies anymore, and what there isn’t much market for, your local video store isn’t terribly likely to carry. This is unfortunate, not only because The Unknown is such a great movie, but also because whoever oversaw its restoration put a hell of a lot of work into it. The picture is beautiful, there are far fewer frame skips than one usually encounters in films of this vintage, and the new score is superb, greatly magnifying the impact of the action onscreen. It may not sound like much, but considering the haphazard way in which modern editions of silent movies are usually scored (the soundtrack to my copy of The Golem, for instance, seems to have been generated by dropping randomly selected classical albums on a turntable, and just letting them play through), it’s a real treat to find one that features first-rate background music devised specifically for that purpose. But despite its rarity, there’s still some chance of you stumbling upon The Unknown if you keep your eyes open. A video store that caters specifically to the tastes of film snobs might plausibly be expected to stock it, and it occasionally plays at inconvenient hours on Turner Classic Movies.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact