Island of Lost Souls (1933) ***

Island of Lost Souls (1933) ***

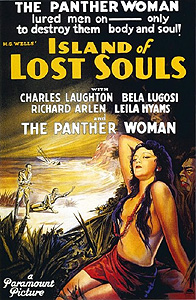

Iíve brought up before, in the context of other reviews, the way that Universalís domination of our modern perception of 1930ís horror movies is even greater than that studioís very real domination of the genre during that decade. Itís true that none of the other big studios made anywhere near as many fright films as Universal did between 1931 and 1936, but with a tiny handful of exceptions, the 30ís horror output of MGM, Paramount, Warner Brothers, and the rest has faded to disproportionate obscurity. Paramountís Island of Lost Souls, the first feature-length film adaptation of H. G. Wellsís The Island of Dr. Moreau, is among those few exceptions, as it very much deserves to be despite a certain clunkiness and a few unfortunate lapses into the ridiculous. It features my nominee for the title of the decadeís most effectively portrayed mad movie scientist and an uncommonly bold handling of what was at the time some extremely controversial subject matter, and has the distinction (which it shares with Tod Browningís Freaks, another atypically high-profile non-Universal horror picture) of having been banned in Britain until some 25 years after its initial release. Itís a safe bet youíre on to something good when the Board of Film Censors wonít even let a movie into the country!

Edward Parker (Richard Arlen, who went on to The Lady and the Monster and The Crawling Hand) is the sole survivor when the Lady Vain, the ship on which he was traveling, goes down in the South Pacific. After several harrowing days in a lifeboat, he is picked up by a passing freighter under the command of the alcoholic and bellicose Captain Davies (Stanley Fields, from Life Returns and Terror Aboard). Davies is on his way to a small, uncharted island at the time, to which he is supposed to transport a rather mysterious ex-surgeon named Montgomery (Arthur Hohl, of The Devil Doll and The Frozen Ghost), his even more mysterious and rather seriously deformed servant MíLing (Tetsu Komai, from East of Borneo and A Study in Scarlet), and a sizable shipment of caged African wildlife before continuing on to Apia. Davies doesnít get along very well with his passengers, MíLing especially. This ends up being an even bigger problem for Parker than it needed to be, for when he sees the captain roughing up MíLing in a drunken fury, he intervenes with the result that he takes the misshapen servantís place at the top of Daviesís hierarchy of scapegoats. At the end of the present leg of the voyage, when the ship rendezvous with another vessel under the command of Montgomeryís boss, Dr. Moreau (the brilliant Charles Laughton, from The Old Dark House and the 1939 version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame), Parker finds himself palmed off with threats of violence upon the two doctors. Davies wants no more to do with any of them.

As you might imagine, an island that isnít worth including on the standard chart doesnít exactly get a lot of sea traffic coming through, so Parker is pretty much stuck unless and until he can convince either of his hosts to take him ahead to Apia in their boat. Moreau promises to have Montgomery do precisely that, but heís rather busy just now, and it will be at least another day or two before they can embark. In the meantime, Parker will feel himself free to enjoy the doctorsí hospitality. Moreau and Montgomery live in a curious, walled compound at the center of their island, inside which stand two or three stone huts with iron bars on all their windows. The fortifications seem like a sensible precaution in light of the savageó indeed, even bestialó appearance of the native islanders, whom Moreau spends the entire trip inland shooing away with an expertly wielded bullwhip.

Thereís more going on here than meets the eye, though, even accounting for the exceptionally ugly natives (from whom MíLing, with his somehow canine face and pointed, hairy ears, was presumably recruited). Once Montgomery has shown Parker to his room, his employer heads over to another part of the compound to pay a visit to a beautifuló but still a bit peculiar lookingó girl he calls Lota (Murders in the Zooís Kathleen Burke). Moreau tells Lota that a man from a faraway country has come to the island, and that she will be permitted to go and talk to him in his room. Lota may ask the newcomer any question she pleases, and discuss with him any topic at all, provided that she steer clear of three subjects: Moreau himself, the law, and the ominously named House of Pain. Sending Lota on her way, Moreau comments to Montgomery that they will now see just how perfect a woman she really is.

So whatís Moreau up to out on his island? As Parker learns when he stumbles upon the doctor hard at work in his laboratoryó that House of Pain he told Lota not to talk aboutó with what appears to be a half-vivisected man on the operating table, Moreau is engaged in a program of medical research that might give even the Nazi doctors of the following decade pause. Those brutish, strangely malformed natives are, inevitably, the end products of that research, but Parker has the process backwards. It isnít that Moreau is turning men into monsters, but rather that heís using a combination of surgery, blood transfusions, and assorted other techniques to turn animals into some semblance of human beings. MíLing, for example, was once a large dog, while the creature on the operating table started life as some manner of ape. Lota, for her part, was originally a panther. She is Moreauís greatest achievement, with only the faintest hint of the beast apparent on her countenance, and it was the doctorís hope that she and Parker would be attracted to each other, mate, and test thereby the true completeness of the transformation Moreau has wrought upon her. And so it might even have been, had Parker not noticed the one way in which Moreau had failed to humanize Lotaó her retractable, claw-like fingernails. The doctor has been at this work for a long time, long enough for his creations to develop an entire miniature society out in the jungle, complete with a chief known as the Sayer of the Law (an unrecognizable Bela Lugosi, in a role as thankless as any he would lower himself to in the 40ís), where Moreau, appropriately enough, is worshiped as God. (As for that Law the head beast-man goes around Saying, it consists mainly of a set of prohibitions meant to imply an affirmative answer to the oft-repeated rhetorical question, ďAre we not men?Ē: not to go on all fours, not to eat meat, not to spill blood, etc.)

Meanwhile, on Apia, Parkerís girlfriend, Ruth Thomas (Leila Hyams, from Freaks and The Thirteenth Chair), is wondering just where in the hell Edward is. She had received a telegram from him, which he sent from Captain Daviesís ship, announcing that he survived the wreck of the Lady Vain, and was now on his way to Apia aboard another vessel. Ruth then caught the next flight to the island, so as to meet him on the dock when the freighter pulled into port. Captain Davies proves obstinately uncooperative until Miss Thomas sics the port authorities on him; with the local commissioner threatening to revoke his captainís license, Davies comes clean about unloading Parker on Dr. Moreau, and even agrees to divulge the location of the doctorís secret hideout. Ruth commissions another captain named Donahue (Paul Hurst) to take her out, thereby giving Moreau three times as many unwanted guests as he had to start with. The doctor is a resourceful guy, though, and can easily find a use for the new arrivals. After all, mating Parker with his new female subhumanoid isnít the only way to find out whether a successful coupling between one of his creations and a natural human is possible.

H. G. Wells hated Island of Lost Souls, and was apparently perversely pleased to see it banned in his home country. He considered it a grotesque vulgarization of his novel, which had been intended as a serious investigation of the moral hazards that might accompany the accelerating advancement of modern science. (This is an interesting point in itself, for Wells was a militant atheist with strong Utopian tendencies and high expectations for how science could remake and improve both the world and mankindó one might almost imagine him writing The Island of Dr. Moreau as a cautionary fable to himself.) Maybe he had a point, but it seems to me that the movie offers a much more concise and powerful statement of his main theme than the novel did, even if it loses some complexity and nuance in the translation to celluloid. One might take issue with the filmmakers for inventing not one but two love interests for the central protagonist (whose name the movie changes for no particular reason), or for telescoping the chain of events that gradually unmakes Moreauís unnatural dominion into a single grisly climax, but both changes serve perfectly valid functions. Injecting sex (and bestiality, at that) into the story plays up Moreauís chilling amorality, while the new and harder-hitting ending simply caters to the requirements of the mediumó in a movie, some kind of dramatic climax is an absolute necessity. And while it does rule out any examination of what becomes of the subhumanoids in the absence of their creator (which is much of the point of the book), the end to which Moreau comes in Island of Lost Souls seems far more fitting than the offhand way in which Wells disposed of him.

Which brings us to the subject of the doctor himself. Charles Laughtonís Moreau is something close to the perfect mad scientist. As Peter Cushing would do with Victor Frankenstein some 25 years later, Laughton gives Moreau distinction by making it clear that he is not mad, at least not in the usual sense. Laughtonís Moreau, like Cushingís Frankenstein, is not psychotic but psychopathic, entirely rational, yet utterly devoid of any moral awareness. To paraphrase Wells, Moreau has never bothered himself about the ethics of his work, focusing upon nothing else but its successó at whatever cost to himself, his associates, or the subjects of his ghoulish experiments. Laughton seems to understand Moreau perfectly, and he plays him as a competent, sensible, clear-thinking man who just happens to have spent his life doing what the rest of the world would consider appalling and unspeakable things for absolutely no practical purpose. Itís an unsettling characterization, and it elevates Island of Lost Souls to a plateau that it might not otherwise have reached.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact