Life Returns (1934) -**

Life Returns (1934) -**

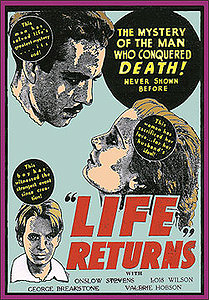

Ladies and gentlemen, I believe Sh! The Octopus may have serious competition for the title of Strangest Mainstream-Studio Movie of the 1930’s. I first learned of Life Returns from— and here’s that title again— Denis Gifford’s A Pictorial History of Horror Movies; Gifford had little to say about it, though, because Life Returns was banned by the British Board of Film Censors in 1935, and was still under interdict when he was writing some 40 years later. Now I’m well accustomed to being baffled by the BBFC’s rulings, but blacklisting Life Returns might just be the silliest thing they ever did. You see, although it was banned as part of the board’s crackdown on horror movies, and although it is frequently described as a horror film even today, Life Returns is in fact no such thing. What it most resembles, believe it or not, is a 1930’s Hollywood take on the Mondo movie, built as it is around about ten minutes of footage recording a groundbreaking medical experiment. Furthermore, the lab footage comes as the climax not to a tale of mad science such as one might expect from Universal (who produced Life Returns in partnership with a very short-lived independent company called Scienart Pictures), but to a sort of science-centric version of the typical Depression melodrama. It’s totally innocuous, totally inoffensive, and totally without condemning social value. In order to regard it as a threat to the moral fabric of society, it would be necessary not merely never to have seen it, but to know even less about it than Denis Gifford did.

Its censorship troubles overseas may be the least of the mysteries surrounding this movie, however. Right up front, one faces the questions of exactly what Scienart Pictures was, what made Universal collaborate with them, and why Universal’s logo appears nowhere on the print that served as the source for the various public domain home video editions. For that matter, given the studio’s usual zeal in safeguarding their intellectual property rights, it’s more than a little curious that Universal would have allowed Life Returns to lapse into the public domain in the first place. And what exactly is this experiment that serves as the movie’s climax? That last mystery is actually the easiest to resolve. According to an article in the March 26, 1934, issue of Time Magazine, Dr. Robert E. Cornish of the University of California (other sources have him attached to the University of Southern California instead) had been striving for some years after a means of reviving patients whose hearts had stopped, but whose bodies were otherwise in sustainable working order. Such resuscitation techniques are commonplace today, but in 1934, Cornish’s studies were out on the far fringe of medical science. On March 17th of that year, Cornish and his assistants took a fox terrier they called Lazarus II, asphyxiated it with a mixture of ether and nitrogen, and set to work restarting its heart six minutes after the last detectable beat. Cornish’s process involved injections of adrenaline and heparin dissolved in heavily oxygenated saline, together with a primitive sort of artificial respiration; the results were mixed. Lazarus II did indeed come back to life, but only for eight hours and thirteen minutes, and he spent those hours in a state of fitful unconsciousness. Cornish’s efforts to jumpstart the dog’s recovery with glucose injections were of no avail, and Lazarus II died permanently when a blood clot formed, inflicting irreparable damage on his vitals.

As for Scienart, it appears to have been little more than a short-term corporate identity for Russo-German producer Eugen Frenke. Frenke, whose only prior credit had been a German version of The Brothers Karamazov, acquired the film of Cornish’s experiment, and evidently thought that somebody ought to be trumpeting the news of his achievement from the rooftops. Somehow, Frenke managed to persuade the bosses at Universal to back him up on a movie that would conclude with the University of California film— and that’s a story I would love to hear, not least because collaborations of any kind between major studios and independent producers were such a rarity in 1934. Frenke’s partnership with Universal must not have worked out to anybody’s liking, though, because Frenke later sued the studio for failing to live up to their end of the distribution bargain, while Universal evidently sold Life Returns to Grand National Pictures, a distributor that dealt mainly in poverty-row Westerns. One suspects that Universal found Frenke’s movie to be at least faintly embarrassing.

That would not come as much of a surprise, if it were true. If ever a movie earned the epithet, “shaggy-dog story,” Life Returns is it. It begins with Robert E. Cornish (playing himself) at med school with his friends and frequent collaborators, Louise Stone (Lois Wilson, of Deluge) and John Kendrick (Onslow Stevens, from Secret of the Blue Room and House of Dracula). A rather charming montage juxtaposes their diligent studies against the campus high life they’ve forsaken, concluding with a stock-footage graduation ceremony that seems to involve just a few thousand candidates too many to be believable at a medical school. After the ceremony, Kendrick presents his friends with a letter he has just received from the offices of Arnold Research Laboratories. Unbeknownst to Cornish or Stone, Kendrick took it upon himself to apply to Arnold for a research grant on behalf of all three scholars, and the eponymous A. K. Arnold (Richard Carle, from The Ghost Walks and The Unholy Three) has agreed to take them on. Think of it, Kendrick enthuses— with backing like that, he and his friends could accomplish in one year what would take them five on their own. Cornish and Stone are not impressed, however. They know that the Arnold labs, despite their philanthropic pretenses, exist mainly to serve commercial enterprise, and while emergency resuscitation measures would certainly be a boon to humanity, it’s difficult to see how Arnold or its sister companies could make money on the project. What’s more, Cornish objects that at a corporate lab, credit for major breakthroughs is claimed for the organization as a whole, whereas he and Stone want to make sure that they personally stand in whatever limelight may eventually shine on their work. Their arguments fail to persuade Kendrick, however, and he goes to work for Arnold without his longtime partners.

He also sets up a successful medical practice, marries a “young socialite” (Valerie Hobson, from Werewolf of London and The Mystery of Edwin Drood), and fathers a son named Daniel (George Breakston, who would grow up to co-direct The Manster with Kenneth G. Crane). His work eats up an enormous amount of company resources, though, without spinning off much of anything in the way of profitable sidelines. Arnold Research is first and foremost a business, as Cornish and Stone once warned Kendrick, and no money-losing venture can survive indefinitely in such an environment. The crisis point comes when Kendrick orders a new and frightfully expensive piece of equipment from his supervisor, Dr. James (Frank Reicher, of Dr. Cyclops and The Return of the Terror). James discusses the matter with Mr. Arnold, and the latter man decides to pull the plug on Kendrick’s research, putting him to work instead in the company’s health-and-beauty division. After all, for a man who’s spent the last ten years trying to raise the dead, it should be no sweat restoring life to women’s perm-frazzled hair, right? Kendrick disagrees. He tenders his resignation immediately.

This is where the Depression melodrama starts. We all know what happens to a man who walks off a perfectly good job in 1930’s America, now don’t we? That’s right— his life turns instantly to shit, and he winds up a broken-down bum! In Kendrick’s case, what sets the downward spiral in motion is his obsessive inability to think of anything other than his interrupted research. He allows his medical practice to fall apart and destroys his reputation with a risky presentation of his premature findings before a university hospital’s medical review board. Dr. Stone is in attendance at the humiliating scene, but her efforts to lure Kendrick back into partnership with her and Cornish meet with the vehement refusal of wounded pride— an interesting reversal of perspectives which Frenke disappointingly fails to take up in any way. Then Kendrick’s wife dies suddenly of unexplained causes, and John goes completely off the deep end. After five years without any sort of income, the State of California steps in and begins proceedings to have him declared an unfit parent. Daniel has no intention of going to Juvenile Hall, however, so he runs away from home with his dog, Scooter, and falls in with a gang of kids from the wrong side of the tracks, led by a boy named Mickey (Richard Quine). At this point, Life Returns pretty much turns into the world’s most depressing Little Rascals short. Daniel takes up residence in the boys’ clubhouse, and spends his days alternately sneaking off to spend time with his dad and running from truant officers. Kendrick slips steadily deeper into dissolution, and none of Daniel’s efforts to pull him out (like the time he tries to get him a job as an elevator operator in a laboratory) have the slightest effect. Scooter is snatched up by a sadistic dog catcher (Stanley Fields, from Terror Aboard and Island of Lost Souls), Daniel has no way to raise the $3.00 necessary for a dog license (three bucks was no trivial sum for a boy in 1934), and the gang’s bid to rescue Scooter from the pound ends with one of the children receiving a compound fracture of the tibia in a fall from atop a fence. When Kendrick proves to be so far gone that he is unable to reset the boy’s shattered leg, Daniel disowns him, and sets off to turn himself in to Juvenile Hall. And then that rat-bastard dog catcher has Scooter put down. Now, you remember how I called Life Returns a shaggy-dog story a couple of paragraphs ago? Well, here’s the punchline: Where do you think Dr. Cornish gets that terrier he raises from the dead?

Maybe one or two of you reading this could dream up a more convoluted way to lead up to that footage of the Lazarus II experiment, but I doubt that it’s within my power. It’s as though two or three completely unrelated movies had dropped dead on the same plot of ground, and eons later some cinematic paleontologist had unwittingly attempted to reconstruct their mingled bones as a single skeleton. Woe betide anyone who comes to Life Returns expecting the Frankensteinian horror flick for which the British Board of Film Censors unaccountably mistook it. It’s hard enough to stomach platoons of bad child actors trying to play tough, schmaltzy attempts at tear-jerking hinging on the plight of dozens of stray dogs, and bizarre comic relief interludes involving daffy middle-aged ladies seeking dream interpretations when you have some idea what’s coming! I can only wonder whom Eugen Frenke imagined to be the audience for this movie, or how those audiences who actually did see it must have reacted in the mid-1930’s. Lord knows I had a hard enough time figuring out what to make of it.

Thanks to Liz Kingsley for furnishing me with a copy of this film.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact