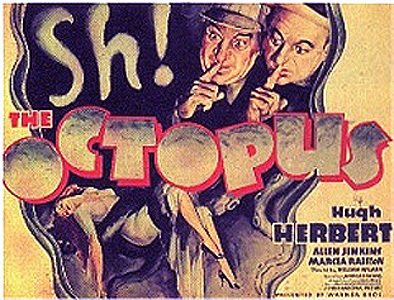

Sh! The Octopus (1937) -**

Sh! The Octopus (1937) -**

Sh! The Octopus, although rarely seen and little remembered today, enjoys several significant distinctions— enough so that it probably wouldn’t be anywhere near as obscure as it is now, were there any commercially viable audience for old-timey movies too long to be packaged in an anthology of shorts, but too short to seem like anything other than a rip-off if released as stand-alone features. (Sh! The Octopus runs about 55 minutes, credits included.) To begin with, it has maybe the weirdest title of any movie released during the 1930’s, if not the whole first half of the 20th century. I can’t imagine anybody learning that somewhere out there, there was a film called Sh! The Octopus without getting just a little bit curious. Secondly, it is one of the few known specimens of a seemingly impossible genre, a parody of a parody. By all accounts, this movie was intended as a spoof of The Gorilla, which had itself been a spoof of contemporary spooky house mysteries like The Bat and The Cat and the Canary. Finally, and most importantly, Sh! The Octopus is quite simply one of the strangest and most utterly illogical mainstream movies of its— or any other— era.

The shadowy and decrepit mansion having become old hat by 1937, Sh! The Octopus moves the action to a supposedly abandoned lighthouse instead. The place has been bought from the government by painter Paul Morgan (John Eldredge, of Horror Island and I Married a Monster from Outer Space) for use as a studio, and he has just arrived on the little island where it stands, accompanied by a sailor named Captain Cobb (Brandon Tynan). Cobb says that no one but the caretaker has been inside the building in twenty years, and him only once a month for inspections; this helps explain the debris-strewn condition of its interior, but raises serious questions when Paul goes to light a candle, and finds the tallow warm and soft, as if it had been burning just minutes before. Cobb also informs Morgan that the stairway leading up into the tower was removed when the lighthouse was decommissioned, though the lamp itself remains. There’s apparently some mystery involved there too, for when Paul asks the sailor what prevented the decommissioning crew from removing the light, Cobb mutters, “Maybe I shouldn’t have said that…” That’s when the caretaker arrives to turn over the keys and inspect the papers formalizing Paul’s acquisition of the place. Cobb had already warned Morgan about this eventuality, for Captain Hook (George Rosener, from Doctor X and House of Secrets), the one-handed caretaker, is a dangerously unbalanced man, and has a habit of flying into a homicidal rage whenever he hears the ticking of a clock. (That, by the way, is easily the funniest and most sophisticated gag in the movie’s arsenal.) Fortunately, Hook does little but glower and threaten upon this occasion, reserving most of his menace for Cobb anyway. Again there are suspicious hints, though. The moment Morgan is out of earshot, Hook rounds on Cobb and demands to know why he brought Paul to the lighthouse tonight, of all nights. Cobb replies that Hook himself called him on the phone to arrange the handover, but Hook denies doing any such thing. Then Morgan returns from the other room with an empty wallet bearing the initials “DDH.” Hook says there’s no such person in the village, but Cobb contradicts him, mentioning a “rich fool from the city” by the name of David Dow Harriman. Harriman was apparently an inventor, but Hook refuses to say anything (or to let Cobb say anything) about what he might have invented. Finally, after the sailors leave, a secret panel slides open in one of the walls to reveal a pair of luminous eyes spying on Paul.

Meanwhile, 49th precinct detective Dempsey (Allen Jenkins) and his pill-popping partner, Kelly (The Black Cat’s Hugh Herbert), are driving down the coast highway when their dispatcher calls to inform Kelly that his wife is in the hospital giving birth. No sooner have the detectives received this news than one of their tires blows, temporarily stranding them about three miles from Paul Morgan’s lighthouse. While Dempsey grumpily works on the tire, Kelly reads in the newspaper that the police department’s new commissioner has declared war on “the giant octopus of crime.” Now any sane person reading that statement would take it as a metaphor— particularly in 1937, when “octopus” was the preferred figure of speech for anything malevolent and multipartite (corporate trusts, criminal organizations, conspiratorial banking concerns, etc.). But scant seconds later, dispatch calls again to alert all units that the schooner Tessie has gone down, and that the distress call reported the sighting of an unknown submarine in the vicinity; headquarters believes that “the Octopus” may be responsible. So apparently the Octopus is an arch-criminal rather than a turn of phrase. Then a young woman runs shrieking to the car from the woods on the left. Her name is Vesta Vernoff (Marcia Ralston, who manages to stand out as a horrible actress in a cast that was pretty horrible all around to begin with), and she says her stepfather has been murdered. Vesta goes on to explain that her step-dad was a scientist who had perfected a radium death-ray “so powerful that whoever controls it could control the world,” that “all the nations of the world” are seeking it, and that the crime was committed in a lighthouse just off the coast. I’m guessing we know who Vesta’s stepfather is at this point. Then Vesta volunteers the most ominous detail of all— beneath the foundation of said lighthouse is the lair of the Octopus.

Presumably we also now know what was going on at the lighthouse right before Paul arrived to take possession of it, and sure enough, Morgan has just noticed the dead body hanging from the rigging of the lamp 100 feet above his head. (He somehow fails to notice the pair of twenty-foot cephalopod tentacles wiggling at him from behind a curtain at the far end of the room at the same time.) Morgan has little chance to think about the puzzle posed by the suspended corpse, for he soon hears the door rattling from the outside, and reasonably decides to hide until whoever it is goes away. It’s Dempsey, Kelly, and Vernoff, of course. The detectives find the body with a little help from Vesta, who then shows them a note she found in Dr. Harriman’s room; the note reads, “Be at the lighthouse at ten tonight. Bring it!” and is signed with a drawing of an octopus. Dempsey and Kelly find Paul when Vesta sees those tentacles Morgan had missed earlier, and the detectives take a look behind the curtain from which they had projected. (And don’t even bother asking me how Paul could have shared the same hiding place with a giant octopus— or a mad genius in an octopus suit, or whatever— without realizing it.) Dempsey and Kelly conclude that Morgan is the Octopus; Vesta rushes across the room, throws her arms around him, and cries, “Oh, Paul!;” and Morgan denies ever having seen either Vesta or the body hanging from the ceiling. And as if that weren’t strange enough, we’ll see confirmation shortly thereafter that Paul and Vesta both know a great deal more than they’re telling the two nitwit cops.

Next, the rest of the cast arrives at the lighthouse in a steady cascade, and the spooky house cliches start coming fast and furious. Captain Hook bursts in carrying a woman named Polly Crane (Margaret Irving), whom he rescued from a motorboat smashed on the reef, and who claims to have been trying to escape from an overly lecherous boyfriend at a house party some way down the shore. Nanny, the Harrimans’ housekeeper (Elspeth Dudgeon, of The Old Dark House), drops in for no very good reason. Captain Cobb rolls out from behind one of the lighthouse’s innumerable secret panels to report having been attacked by the Octopus. Eventually, even a man purporting to be Commissioner Clancy (Eric Stanley) puts in an appearance. The lights go out a lot, the women scream at nothing even more often, and virtually every square inch of the lighthouse’s interior turns out to have something secret hidden behind it. Lots of characters get the shit kicked out of them offscreen. Tentacles close and lock all the doors to the outside, and somebody floods the lighthouse with poison gas. Our heroes find the warren of sea caves beneath the lighthouse, and Kelly has an underwater battle with a rubber octopus that makes the one in Bride of the Monster look positively respectable. Absolutely every character except for the two idiot detectives is revealed to have a secret identity, the Octopus naturally proves to be the least likely suspect of all, and incredibly, we find in the end that it was all just a dream. Whatever else we may say about it, Sh! The Octopus certainly didn’t leave out any of the standard plot twists!

As the woeful incoherence of the foregoing attests, Sh! The Octopus is nearly impervious to synopsis, let alone analysis. There is no apparent structure or plan to the screenplay, which is simply nothing more than a stream-of-consciousness litany of genre commonplaces, in which plot threads fall by the wayside almost as rapidly as they are introduced. Theoretically, the movie is a mystery, but nothing could be further from the truth. Mysteries have clues; their villains have motives; their heroes use logic and reason to fit the pieces of the puzzle together. In Sh! The Octopus, on the other hand, there isn’t even really a crime to be solved, as it is revealed relatively early on that the body hanging from the ceiling is in fact a stuffed dummy! The one thing stopping me from nominating Sh! The Octopus as the single stupidest horror or mystery film of the 1930’s is the disconcerting possibility that its creators understood exactly what they were doing. Remember, Kelly turns out to have dreamed the whole thing. That being the case, doesn’t the tangent off of tangent off of tangent non-structure that characterizes the plot have a certain ass-backwards logic to it? Don’t the frequent occasions on which one character or another puts forward a piece of terribly convenient information that they have no reason to possess, or the constant confusion over whether the Octopus is a criminal mastermind or a big rubber monster, make a kind of cockeyed sense? Isn’t that exactly the way dreams really work?

I don’t know what or how much to make of that possibility, though, because the fact remains that this was a no-budget, disposable second feature, and movies of that ilk very often were only a little less idiotic than Sh! The Octopus seems on its face. Furthermore, it was intended primarily as a comedy, and comedies of this vintage frequently made only the most ritualistic pretense of telling a comprehensible story. Instead, the typical comedy screenplay of the 1930’s might best be thought of as a framework on which to hang some vaudeville or radio comic’s regular shtick, and that looks to be what happened here to at least some extent. At first glance, it seems odd that Hugh Herbert, who plays the sidekick to a character whose actual contributions to the so-called plot are marginal at best, would receive top billing. Herbert was one of Warner Brothers’ more popular contract comedians at the time, though, and his portrayal of Kelly as somewhat dim, easily distracted, and conspicuously neither brave nor competent was apparently in keeping with the stock persona that Herbert had developed by the mid-1930’s. Kelly’s habit of punctuating nearly every utterance with weird hooting noises has been cited everywhere I’ve looked as a Hugh Herbert trademark, too. My regular readers will not be surprised to learn that I didn’t find Herbert, or anything else in Sh! The Octopus, to be the slightest bit funny, or at least not for the reasons they were supposed to be funny. But it would be a tall order indeed to make a movie as thoroughly fucked-up and irrational as this one, and still leave me completely cold— especially if you’re going to fire up the closing credits after substantially less than an hour!

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact