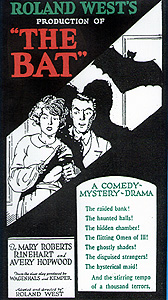

The Bat (1926) ***

The Bat (1926) ***

I call them the Colorful Killer movies. Perhaps the most consistently entertaining subspecies of the spooky house mystery, these early films (many if not most of them silent) pitted a more or less elaborately costumed murderer against the usual bunch of innocent and not-so-innocent potential victims, generally with the point of contention being some fabulous quantity of hidden cash or jewelry. What I personally find so fascinating about them is that, in addition to their more obvious influence on everything from the avowedly supernatural haunted house films that succeeded them to the superhero comics that started cropping up just as the cycle was beginning to wind down, the Colorful Killer movies seem to me to be the first recognizable step along the road to the modern-day slasher flick. Take a good, close look at the monkey-faced killer stalking the secret passages of Garth Manor in Hell Night, and then tell me he doesn’t remind you just a little of the talon-handed, fang-toothed, bulgy-eyed maniac stalking that other set of secret passages in The Cat and the Canary. Is there honestly all that big a difference between Walter Pidgeon (or his successors in the various remakes) dressing up like an ape to conceal his identity in The Gorilla and the New York Ripper’s bizarre habit of affecting a Donald Duck voice when he terrorizes his victims-to-be over the phone? Hell, stand The Terror’s cloaked and hooded killer up next to Ghostface from the Scream movies— just about the only difference there is that that damned Edvard Munch painting wasn’t yet staring down from the wall of every college dorm room in America in 1928. While the formulas into which they fit of course differ substantially, today’s slashers and yesterday’s Colorful Killers are very much the same basic breed of character.

As for Roland West’s The Bat, it’s one of the earliest movies of its type that still survives. The story, derived ultimately from Mary Roberts Rinehart’s novel, The Circular Staircase, had been filmed previously under the original title in 1915, but that version appears to be lost now. Rinehart, together with Avery Hopwood, had also adapted The Circular Staircase to the stage in 1920 (at which point it was rechristened The Bat), where it proved so successful that it broke records for longevity on Broadway. With such a strong track record, The Bat would have seemed the natural property for West to exploit as a follow-up to his 1925 movie version of Crane Wilbur’s The Monster (first performed in 1922), especially since both plays featured a similar mix of mystery, horror trappings, and crude comedy. But whereas West fumbled badly with The Monster, even despite the casting of Lon Chaney as the primary villain, he did a much better job with The Bat, striking a more workable balance between (actual) horror and (mostly notional) humor, while giving his new movie a striking and memorable look that incorporates many of the innovations of the German Expressionists. It goes wrong in places, to be sure, but The Bat holds up astonishingly well across the ages.

We open on the New York penthouse apartment of one Gideon Bell (George Beranger, from The Avenging Conscience and The Walking Dead), a well-known jewelry collector and the current owner of “the fabulous Favre emeralds.” Bell has recently received a letter from a man calling himself the Bat, who helpfully warns Gideon that he’ll be stopping by at midnight to relieve him of the emeralds, and that there’s not a goddamned thing Bell or the police will be able to do about it. And indeed there is not. At the stroke of midnight, Bell hears a strange sound outside his window, and when he goes to investigate, the costumed man hanging by a rope from the roof garrotes Gideon, and helps himself to the gems. The Bat also leaves a taunting note behind for the police to discover, announcing that he’s off to the country upstate for a little relaxation.

“The country” turns out to be Oakdale County, where the Bat means to rob the Oakdale Bank. Unexpectedly enough, however, a man in a black hat and raincoat, with a black bandana tied around his face (Charles Herzinger), has beaten the Bat to the punch. The man in black makes off with some $200,000 while the Bat is still busy picking the locks on the skylight. In frustration, the Bat trails the other thief’s car halfway across the county to the immense, sinister mansion owned by Courtleigh Fleming— and I’m guessing it isn’t quite a coincidence that Fleming is also the owner of the Oakdale Bank.

Actually, that should have been “was.” As it happens, Fleming has just recently died while on some sort of holiday out in Colorado, and ownership of all his property has devolved upon his son, Richard (The Intruder’s Arthur Housman). Richard has mountains of gambling debts, and it looks to me like a fair proportion of them are owed to family physician Dr. H. E. Wells (Robert McKim), who suspiciously counsels the younger Fleming to clear the tenants out of the family mansion not too long after Bandanaman and the Bat converge on the property. Those tenants are Miss Cornelia Van Gorder (Emily Fitzroy); her niece, Dale Ogden (Jewel Carmen); and her “comically” high-strung maid, Lizzie Allen (Louise Fazenda, from The Terror and House of Horror). And as if matters weren’t already complicated enough with two masked thieves, a hazardously indebted tycoon, and a scheming doctor poking around the Fleming house, Dale just happens to be dating Brooks Bailey (Jack Pickford, of Ghost House), the Oakdale Bank teller who was on duty when the robbery occurred, and who has since disappeared under a cloud of suspicion. Indeed, he’s disappeared to the Fleming house, where Dale is trying to pass him off as a gardener. Oh— and there’s a sinister Japanese butler (Kamiyama Sojin, from The Unholy Night and the 1924 The Thief of Bagdad), basically because you can’t have a movie like this one without a sinister butler of foreign extraction.

So is anybody going to be surprised when detectives start showing up at the mansion? No, I didn’t think so. Indeed, we get two separate detectives this time around, one from the police department and one from a private agency. Around the time that Police Inspector Moletti (Tullio Carminati) is putting together the clues that will lead him to the Fleming place, Cornelia and Lizzie get so freaked out over a series of strange goings on that they hire their own investigator, “Bulldog” Anderson (Eddie Gribbon), to look over the house in search of the notorious Bat. Anderson, in case you couldn’t have guessed, is really a coward despite his bluff demeanor and the two farcically enormous pistols he carries in the pockets of his overcoat. Hey— we’ve got every other stock character type in the book here; we might as well have a chickenshit private eye, too.

Moletti and Anderson set about questioning everyone in the house, duplicating each other’s efforts and generally getting in each other’s way. Meanwhile, people keep glimpsing both the Bat and Bandanaman prowling around the mansion, and there is much talk of a secret room hidden somewhere in the house, wherein the bank robber presumably stashed the $200,000 upon his arrival the other night. Then Richard Fleming is gunned down from the top of a staircase by somebody who has the criminal acumen to use a flashlight to blind Dale and Dr. Wells, the only witnesses to the crime. Because Dale herself happened to be carrying her aunt’s revolver at the time the fatal shot was fired, Moletti figures her for a suspect, and he becomes doubly convinced of her guilt when he puzzles out who Brooks Bailey really is, and discovers that he and Dale are engaged to be married. Further complications arise when a hitherto unknown man (Lee Shumway)— battered, bloody, and apparently stricken with amnesia— staggers into the house from the rear garden. Finally, Brooks happens to see Bandanaman without his mask, and realizes that he knows the mysterious man very well indeed. Bandanaman inadvertently leads Brooks to the secret room, and Brooks inadvertently leads the Bat to it in turn. The clash between the two arch-criminals leaves the Bat victorious, allowing him to devote his full attention to ridding the Fleming mansion of the remaining interlopers.

If nothing else, The Bat is an absolutely beautiful film. Roland West’s extensive use of miniature models to stand in for establishing shots of locations which he could never afford to build for real was groundbreaking, and allowed him to get exactly the look he wanted for such crucial exteriors as the Fleming mansion, the Oakdale Bank, and Gideon Bell’s apartment complex. That dedication to achieving the perfect production design extended to the regular sets as well, the majority of which exhibit a wonderfully eerie combination of Art Deco and German Expressionist elements which really sets The Bat on a plane above and in a class apart from most of the next twenty years’ worth of spooky house mysteries. The costume for the title character also deserves special mention. To be fair, it’s a bit overdone, and it is indeed beyond impractical as the disguise for a jewel thief and bank robber. That said, however, the mask especially is extremely cool (once you get used to those titanic ears, anyway). In striking contrast to what we’d see in the better known remakes, the Bat’s mask in this incarnation makes him look more like some kind of chiropteran gargoyle than a guy in a funky suit— if somebody had bothered to make a Man-Bat movie in the early 1970’s, they could have done much worse than to copy what West’s costumers came up with here.

It isn’t in looks alone that The Bat represents a quantum improvement over West’s earlier The Monster, however. Though there is no single cast member with anything like Lon Chaney’s abilities, what talent there is here is distributed far more evenly, and the script is written in such a way as to give all of the major players something worthwhile to do. And of the greatest importance, The Bat keeps its horror/mystery elements and its comedy in a workable equilibrium, preventing the latter from drowning out the former in all but a handful of truly insufferable scenes. This movie treats its characters much more roughly than The Monster had, and both the Bat and his black-clad rival pose a far more credible threat than the earlier film’s quartet of kitschy madmen. The question of just how all the different and competing underhanded agendas fit together is a compelling one, and serves to hold audience interest no matter how badly bogged down the film threatens to become. Even a bit of the humor works this time around, and in a way that’s fascinating to watch. As is so often the case in very old films, The Bat’s straightmen get all the really funny lines, but what’s so curious here is that this comes across even in the absence of a dialogue track. Emily Fitzroy in particular does an excellent job of pantomiming the necessary dry wit; you can almost hear the deadpan tone with which she skewers Lizzie, Brooks, and Bloodhound Anderson. Most antique spooky house flicks sorely tax my patience, but I had no such problem with The Bat.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact