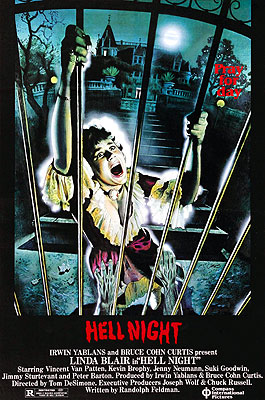

Hell Night (1981) ***

Hell Night (1981) ***

Why the hell haven’t more people seen this movie? You’d think Linda Blair in a slasher flick would have packed them in! And yet, 20 years later, Hell Night is all but forgotten, while fucking Silent Night, Deadly Night has four useless sequels. I just don’t get it. Perhaps it wasn’t bloody enough for the hardcore slasher fans. Certainly, the carnage on display here is a bit less explicit than that in the early Friday the 13th movies, and there isn’t nearly as much of it. But even so, we’ve got an excellent, if only briefly glimpsed, decapitation and a nice little impalement by scythe, so it isn’t as though Hell Night has nothing to offer the Fangoria subscribers. Not only that, it has something very much like a real story, characters who are more than just Expendable Meat, and— lest you forget— Linda Blair!

On the other hand, it sticks close enough to the accepted formula to satisfy whatever weird psychological craving we slasher fans have that keeps us watching these movies even though we usually know within the first ten minutes exactly how everything is going to turn out. Marti (our darling Linda, of The Exorcist fame) is a new pledge to the sorority arm of the Alpha Sigma Rho fraternity. When first we see her, she is attending a costume party at the frat house in celebration of “Hell Night,” the climax of the fraternity initiation process. As frat president Peter Benton (Time Walker’s Kevin Brophy) explains, Marti and the other new pledges— Jeff (Peter Barton, from Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter), Seth (Vincent Van Patten, of Rock ‘n’ Roll High School), and Denise (Suki Goodwin)— will later have to spend the night inside the old Garth mansion not far from their college’s campus. Garth Mansion was the scene of a horrible multiple murder 12 years ago, when Raymond Garth killed himself, his wife, and three of his four freak children. But when the police arrived on the scene, only three of the expected five bodies were present, and there was no sign of the fourth child, 14-year-old Andrew Garth. Ever since, it has been rumored that Andrew— driven crazy by the grisly spectacle his father forced him to witness— still lives in the otherwise abandoned house, keeping out of sight by spending most of his time in the rather improbable network of tunnels and secret passages that riddle the ground on which the mansion stands. The potential that such a house holds as an instrument of fraternity hazing ought to be obvious.

Marti, Jeff, Seth, and Denise are duly driven to the Garth place, and the main gate to the grounds is ceremoniously locked behind them. From then until dawn the next day, the four pledges will be on their own with whatever may lurk in the old mansion. While the pledges pair off in order to get to know each other (and Denise’s Quaaludes) better, Peter Benton gets together with Scott (Jimmy Sturtevant) and May (Jenny Neumann, from “V” and Mistress of the Apes), two other Alpha Sigma Rho members, to put the “Hell” in Hell Night for Marti and company. Scott has the house rigged with lots of little electronic gizmos designed to scare the shit out of pledges. We’re talking hidden speakers to project tape-recorded screams and ghostly moaning, spring-loaded skeletons secreted in closets, concealed projectors that can somehow cast the images of guys in fright masks onto thin air, and some kind of device on the roof that drops a masked dummy down in front of a window two stories below when its mechanism is triggered— and that’s just a list of the highlights. (I’d like to take a moment now to draw your attention to the fact that all these contraptions have been set up in a house that was never wired for electricity!)

Peter’s scare tactics certainly have their intended effect, but the frat president has more on his hands than he bargained for this year. Marti, Jeff, Seth, and Denise, you see, are not the only ones in the house. Somebody (Andrew Garth, perhaps?) is prowling around on the grounds, and whoever he is, he seems to find fraternity hazings an especially annoying intrusion on his privacy. Our mystery man starts with May, whom he decapitates the moment she separates from Scott to carry out whatever part of the Hell Night scheme had been delegated to her. Then the killer climbs up on the roof to do away with Scott, replacing the dummy on the pulley with the dead boy’s body. Peter’s turn comes when he finds Scott’s corpse— the killer corners him in the hedge maze in the garden, and runs him through with a scythe. Finally, with all the hazing perpetrators out of the way, the murderer turns his attentions to the unsuspecting pledges.

This is where Hell Night starts taking chances with the usual formula. In the end, more of the action turns out the way you’d expect it to than not, but there are a few legitimate surprises along the way. Sure, horny libertine Denise comes to a sticky end, and is the first of the pledges to get taken out. Sure, the adult authority figures prove to be of no damn use at all when the axes start swinging (though, truth be told, that’s really more of an alien-invasion movie cliche than a slasher convention). And sure, Marti ends up being the Final Girl, while nice-guy Jeff’s attempts to rise manfully to the occasion go disastrously wrong. The usual scene in which the protagonists discover the killer’s secret lair is also in evidence. However, notice that each of these events is preceded by a buildup that suggests the movie may not go in the expected direction after all, and note how much closer to success Seth’s rescue attempt comes than its counterparts in other slasher films from the 80’s. If only he’d paid a little more attention to the legend of the Garth Mansion Massacre, he might have known to be a bit more cautious after his initial apparent victory.

Hell Night is able to get some extra mileage out of its willingness to play around with your expectations because of the effort its creators put into making most of its important characters more than just stock types. Final Girls are almost always depicted with relative care, so it isn’t surprising to see some layers to Marti’s character, but the extra dimensions displayed by the other pledges— and even one of the frat boys!— are another matter. Less use is made of the information than ought to have been, but Jeff’s embarrassment at his family’s wealth and Seth’s hunting and surfing hobbies at least hint that the characters have lives apart from their ordained roles as victims of the Garth Mansion murderer. And Seth’s ability to drop his smirking party-animal facade and rise to the occasion when he finds himself and his fellow pledges in real danger is wholly unexpected. Frat boy Scott is another character of far greater nuance than is typical for the genre. Though the script never says so in precisely these terms, it’s clear that Scott is an ex-nerd who was able to rise to a more desirable social station because Peter Benton saw that Alpha Sigma Rho had a use for him and his skill in the nerdly arts. But Scott still never seems quite at ease in the social milieu of the fraternity, and his interaction with Peter leaves no question about who it is at Alpha Sigma Rho to whom Scott owes his acceptance by the rest of the brothers. All in all, it’s enough to make me turn a blind eye toward what would otherwise be damning defects in the movie’s plot. (If Garth Manor is the traditional site of Alpha Sigma Rho’s initiation proceedings, for example, why the hell hasn’t anything like this ever happened before?)

Now I generally don’t do this, but I think I need to spend the rest of this review responding to another reviewer’s comments, because they were all I could think about as I watched several of the scenes in this movie. The critic I refer to is Carol Clover, who repeatedly brings up Hell Night in the slasher chapter of Men, Women, and Chainsaws, her study of gender in post-70’s horror movies. I take issue with a lot of what she has to say, but whatever complaints I have with her book as a whole, I have to give Clover major credit for one thing— hers is the only scholarly work on the subject I’ve ever read that didn’t make me say, “now wait a minute... have you ever actually seen any of these movies you’re talking about?!” Men, Women, and Chainsaws is the only book of its type that I have run across that takes slasher movies at all seriously, and does not dismiss the entire subgenre out of hand as nothing more than an extended exercise in misogynistic sadism. It contains a number of extremely astute observations about what it is that differentiates modern horror movies from those made before the mid-1970’s, and not the least of these concerns the very different role of the heroine in films on either side of the divide. Seemingly alone among the ranks of scholarly and professional critics, Clover has noticed that the central character of the slasher movie is almost invariably female, and that, in stark contrast to the heroines of older horror movies, slasher heroines’ dramatic roles are not limited to screaming, fainting, and waiting passively for some man to come along and rescue them. Not only that, in most movies of the slasher and related subgenres, this heroine comes to dominate the film so completely that the final act is presented almost entirely from her point of view. Clover rightly points out the fatal effect this fact has on the widely accepted notion that slasher movies are made by and for knuckle-dragging woman-haters, and that the sympathies of both audience and filmmaker lie invariably with the killer. She raises the obvious point that something demanding an explanation must be going on when a genre whose audience is overwhelmingly male evolves into a form that presents few if any masculine roles worth identifying with, and yet manages to keep that male audience’s loyalty.

But Carol Clover is a neo-Freudian, so as sound and insightful as her observations about modern horror movies are, her analysis of the phenomena she observes is often ridiculously far-fetched. She reads the slasher movie as either a dramatization of the Oedipal complex— in which the Final Girl really represents the boy on the threshold of maturity, who must overcome the Oedipal father-figure (the slasher) by seizing control of the phallus (the chainsaw/butcher knife/power drill) for himself, thereby symbolically castrating the father— or as some sort of means for young men to experiment with issues of sexual/gender identity without having to, say, actually fuck other boys. Clover’s main evidence for these interpretations is the characterization of the Final Girl. Clover notes that this character is generally far less traditionally feminine than the other females in slasher films. She is rarely the prettiest girl in the movie (at least in conventional terms— note that Linda Blair, though not exactly horse-faced, is short, plump, and dark-haired, while Suki Goodwin and Jenny Neumann are both tall, skinny, and blonde), she usually has some sort of interest that is typically considered masculine (Marti works as a mechanic, and when the killer attacks her, she is able to hotwire a getaway car), and she exhibits a take-charge attitude that would have been considered almost unseemly 50 years ago (when Jeff insists on going to look for the killer, Marti insists on going with him— not because she’s scared, but because she thinks Jeff will do something stupid and get himself killed without her to look after him!). And just in case you hadn’t yet gotten the androgynous point, Final Girls often have sexually ambiguous names— and “Marti” seems like as good an illustration of that point as you could ask for. (Interestingly enough, those few movies with Final Boys tend to do the same thing, presenting us with guys named “Jesse” and “Ashley.”)

All of Clover’s observations about Final Girls are certainly true as far as they go, but might there not be a simpler explanation for them than Oedipal complexes and homosexual insecurity? For example, couldn’t it be possible that the character of the Final Girl represents a deliberate attempt on the part of the creators of slasher movies to come up with a female character that young males will relate to? There are good and compelling reasons for making a horror movie’s main potential victim female. Women are, on average, smaller and physically weaker than men. Not only that, there is a long cultural tradition in the West of viewing women as somehow inherently vulnerable and in need of protection. So most audiences, when presented with some burly guy with a mask and a machete, can be counted upon to respond more strongly if they see him menacing a teenage girl than they will if his intended victim is, for example, the star quarterback of a college football team. And most makers of exploitation movies have little interest in taking chances— if most people will fear more for a woman’s safety than they will for man’s when there are axe-murderers about, then the victims will fucking well be female. But by making the main character female, those same exploitation filmmakers may run the risk of losing the interest of their mostly male audience. What better way to insure against that than by giving the woman in question interests and qualities that men will relate to and identify with?

And while we’re at it, we ought also to consider the fact that the great bulk of the slasher genre is made up of ripoffs of Halloween, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and A Nightmare on Elm Street (or ripoffs of others that rip them off in turn)— all movies made by talented, intelligent filmmakers who aren’t afraid to act in defiance of convention. It is entirely possible that John Carpenter, Tobe Hooper, and Wes Craven were deliberately trying to shake things up by putting a woman at the center of their movies and transferring most of the duties of the hero to her. When it worked for them (and had it not been for The Blair Witch Project, Halloween would still be the most profitable independent horror movie ever made), the makers of movies like The Prey probably just jumped on what looked like the most promising bandwagon on the road. Certainly, that scenario makes a hell of a lot more sense to me than the idea that slasher movies look the way they do because millions of teenage boys have Oedipal complexes or are afraid they might be gay.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact