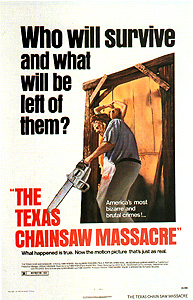

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) ****

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) ****

The Battalion of Saints were right— America loves its serial killers. More than any other nation with the possible exception of Great Britain, the United States extends to its most pathological murderers the opportunity to transform themselves into a twisted sort of pop-culture icon. Rarely are true-crime books absent from the bestseller lists, there are entire cable TV channels devoted to the subject of lurid and bizarre tales from the annals of law enforcement, and many of the country’s most spectacularly warped human predators have become household names. If we can be said to have a favorite, there’s a good chance that Charles Manson still deserves the title, though for a while there it looked like Jeffrey Dahmer was on his way to eclipsing him. But the makers of horror movies have a different number-one real-life bogeyman. After Jack the Ripper (who, because he was never caught, allows the greatest leeway for dramatic license), I can’t think of a serial killer who has inspired more celluloid nightmares than Plainfield, Wisconsin’s Ed Gein.

There’s good reason for this; Gein’s story is the kind of thing you’d be tempted to dismiss as too far-fetched in its grotesquerie if you had made it up. Though no one’s quite sure just how many people Gein killed before he screwed up and got caught in 1957, the police found the remains of at least fifteen women when they raided his secluded farmhouse. Most of these probably weren’t murder victims, but rather the spoils of his prolific career as a grave robber in the years before he switched to serial slaughter. Nevertheless, it was a pretty gruesome scene that confronted the cops on the night of Gein’s capture. The way Moira Martingale tells it in Cannibal Killers: The History of Impossible Murders,

Mrs. Worden’s head was found with two hooks in the ears, ready for hanging on the wall. The house was filthy, littered with old newspapers and the rotting remains of meals. As if stuck in a time-warp, it appeared to have been untouched since the death of Gein’s mother twelve years previously. The remains of Mary Hogan were found in a house which was like an abattoir. In the basement parts of human bodies hung from hooks on the walls and the floor was thick with dried blood and tissue. In the kitchen, four human noses were found in a cup and a pair of human lips dangled from a string like a grisly mobile toy. Decorating the walls were ten female heads, all sawn off above the eyebrows, some with traces of lipstick on the cold, hard lips. The refrigerator contained frozen body parts. A human heart— Mrs. Worden’s— was in the pan on the stove. And there was an armchair… with real arms. |

That wasn’t the half of it, either. Gein was nothing if not multitalented, and the roster of objects in his home which had started out as pieces of somebody else’s body included tables, bedposts, dishes made from skullcaps, a chair upholstered with human skin, and even a similarly derived drum with a coffee tin for a shell. But mostly what Ed Gein made out of his victims and body-snatching trophies was clothing. The skins of an unknown number of women, both living and dead, ended up as socks, vests, leggings, bracelets, and an especially ghoulish nipple-studded belt. And while dressing up in women’s skin, Gein would complete the illusion by donning masks made from their faces and panties into whose linings their vulva had been sewn. It should thus come as no surprise that Gein wanted desperately to become a transsexual; in fact, he apparently began digging up women from the cemeteries of rural Wisconsin in order to dissect them and figure out how they worked, perhaps with an eye to carrying out the surgery on himself one day. (Gein started committing murder to acquire his raw materials when the feebleminded old man whom he had talked into helping him dig up graves finally became as soft in the muscles as he was in the head.) After each “experiment,” he would save whatever parts took his fancy and then cook and eat the rest. Worse yet, there is reason to believe that Gein made unwitting cannibals of his neighbors by giving them cuts of human meat which he passed off as venison! And as is so often the case with the most grievously fucked-up pathological killers, Gein got his initial push toward madness from his controlling, domineering, religious nutjob mom.

This is starting to sound familiar, isn’t it? Over the years since his capture and confinement to the psych ward at Mendota State Hospital, Gein has turned up on film again and again in various guises. He can be seen at the Bates Motel, dressing up like his mother and sticking a carving knife into Janet Leigh. He’s there as the Butcher of Woodside, digging up graves to get replacement parts for his poor, dead Mama in Deranged. It doesn’t take a whole lot of imagination to spot him under the alias Buffalo Bill in The Silence of the Lambs. For that matter, recent years have even given him his own out-and-out biopic, creatively entitled Ed Gein. But for my money, the Gein-inspired film that best captures the man’s utter and incomprehensible monstrousness is Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

After a brief opening crawl that plays the docudrama card by calling the Texas Chainsaw Massacre “one of the most bizarre crimes in the annals of America,” the movie begins with the best example of the “whack the audience over the head with something awful right off the bat” approach to horror filmmaking that I’ve seen in a very long time. While a voiceover (which we are given to understand is coming from a radio news announcer) explains that a cemetery in Muerto County, Texas, has been horrifically vandalized once again by a serial grave-robber, we are shown brief peeks of one of the disinterred corpses, apparently illuminated solely by the flashbulbs of police photographers documenting the scene. Now as you might expect, word that Muerto County’s dead are being dug up and turned into macabre art installations has just about everybody in Texas with a loved one buried in the affected boneyard rushing in to make sure Grandpa or whoever is still safely in the ground. That’s what brings college-aged Sally Hardesty (Marilyn Burns, from Eaten Alive and Kiss Daddy Goodbye) and her wheelchair-bound brother, Franklin (Race With the Devil’s Paul A. Partain) to town, along with their friends, Kirk (William Vail, who later played tiny parts in Poltergeist and Mausoleum) and Pam (Teri McMinn), and Sally’s boyfriend Jerry (Allen Danziger). Granddaddy Hardesty mercifully proves to be right where his kinfolk left him, and the five kids climb back into Jerry’s van and drive off in the direction of the old homestead, looking to take a trip down memory lane.

I’m convinced that it’s because I’ve seen so many movies like this one that being way out in the country gives me the willies. On the way to their destination, the kids come upon a hitchhiker (Edwin Neal, of Future Kill) waiting by the road near the slaughterhouse where the Hardesty siblings’ father used to work, and at Pam’s instigation, they stop to give him a ride. Big mistake there. It doesn’t take long for Sally and company to figure out that the hitchhiker is not merely a bit retarded, but completely out of his mind. Turns out he used to work in the slaughterhouse, too— on the killing floor, back before mechanization made his job redundant. It’s bad enough that he insists upon talking to his fellow passengers about the details of cattle slaughtering and head-cheese manufacturing, but the creepiness reaches a whole new level when he takes an inordinate interest in the lock-blade knife with which Franklin has been cleaning his fingernails. The hitchhiker grabs Franklin’s knife and plays with it for a bit, then suddenly starts using it to slice open the palm of his own hand! The understandably rattled Kirk gets the knife away from him and gives it back to Franklin, but the hitchhiker isn’t quite disarmed yet. He’s got a blade of his own, you see— a rusty straight razor he keeps in his boot, and which he now proceeds to show off, along with his ancient Polaroid camera. He puts his razor down long enough to snap a picture of Franklin, in exchange for which he demands to be paid two dollars; when Franklin refuses, the hitchhiker sets the photo on fire, and then slashes Franklin’s forearm with the razor. Kirk finally gets the hint at this point, and manhandles the hitchhiker out of the van.

The day doesn’t get any better for our heroes from there. Jerry’s van is running low on fuel, but when he stops at a run-down general store/gas station to rectify the situation, the man in charge (Jim Siedow) tells him the tanks beneath the pumps are empty, and the truck won’t be coming along to refill them until tomorrow morning. Jerry and the attendant talk for a while, as the boy tries to figure out whether or not there’s anywhere else to get gas in the vicinity and the shop owner tries to interest him and his companions in some home-cooked barbecue. (Note that every time the owner moves away from the van in the direction of his front porch, the hydrocephalic cretin who works for him stops washing the windshield, and every time he comes back over to resume the conversation, the halfwit gets out his sponge again.) The funny thing, though, is that the man changes his tune about when the tanker truck is supposed to be arriving once Jerry mentions that he and his friends are from out of town. Hooper handles this very subtly; you’re not supposed to notice, and you probably won’t the first time you see it, but that truck the shopkeeper wasn’t expecting until the morning now “ought to be along in a little while,” allowing Jerry to get his tank filled if he’ll just stick around. Franklin and his sister really want to have a look at their grandfather’s old house before the sun goes down, though, so the kids merely buy some smoked meat and leave.

Grandpa’s house proves to be in pretty decent shape for a building that last saw occupancy some fifteen years ago, and Sally has a big old time showing Jerry, Kirk, and Pam around the place. Down on the first floor, however, Franklin has picked up on a couple of eerily discordant notes in the scenery. Sure, it’s just a few owl feathers and animal bones, but something about the way the things are piled on what’s left of the back porch looks ominously deliberate. Be that as it may, Franklin says nothing when Kirk and Pam come downstairs to ask him where they can find the old swimming hole he had mentioned was nearby, telling them only that it’s at the end of the path that runs out from the back yard between a pair of sheds. Kirk and Pam find the pond dried up when they get there, though, and their attention swiftly turns to the house they can dimly make out through the trees on the other side of the hole. Then Kirk notices that he can hear a gas generator running somewhere on that house’s property, and realizes that he may have found the solution to the van’s fuel woes. He and his girlfriend leave the long-dead swimming hole, and head off to the house in the hope of bartering for gas.

It dawns on Kirk and Pam only gradually, but the house and its environs are just plain wrong. Beyond the fact that there doesn’t seem to be anyone around despite the generator running noisily in the yard, the area is littered with things that just shouldn’t be there. First the two youths pass by what looks like a campsite that somebody abandoned in a hurry a long time ago. Then they find at least a dozen rusted-out old cars hidden under what I can only interpret as a huge swatch of camouflage netting. Finally, when Kirk enters the house itself (Pam stays out on the porch), he finds it filled with all manner of sinister bone-and-feather trophies— obviously more developed versions of the things Franklin saw at his grandfather’s house. Actually, that isn’t quite the final thing marking the house as a Bad Place. The truly final tip-off comes when a huge man in a butcher’s apron and a crude, apparently homemade leather mask suddenly appears from behind a corner beneath the house’s main staircase, and cracks Kirk on the forehead with as big a hammer as can comfortably be wielded with one hand. The masked man (Gunnar Hansen, from The Demon Lover and Hollywood Chainsaw Hookers) catches Pam, too, when she comes inside to see what her boyfriend is up to. But rather than kill her immediately with his hammer, he merely stuns her and hangs her on a meathook above a washtub in the kitchen, putting her out of the way while he fires up a chainsaw and starts taking Kirk apart with it.

About an hour later, Jerry leaves Sally, Franklin, and the van to go look for Kirk and Pam, who should certainly be done with their swim by now. He too spies the house on the far side of the swimming hole and blunders into the masked killer’s clutches when he goes inside to inquire after his missing friends. At last, when night has fallen and Jerry still hasn’t returned, Sally and Franklin go looking themselves. They are ambushed before they even get to the house, and Franklin is butchered where he stands (or sits, I suppose). Sally, on the other hand, is able to take advantage of the killer’s preoccupation with her brother to get a head start on running away; unfortunately, she makes the mistake of fleeing to the madman’s own house, where she is nearly cornered and killed. Eventually, she makes it all the way out to the general store where her friends had stopped before. The good news is that the old man who runs it hasn’t yet gone home for the night, and the chainsaw-wielding killer doesn’t press the pursuit once his quarry has reached someone she can tell about what has happened to her this evening. The bad news is that this is because the storekeeper is also the killer’s father, and that crazy hitchhiker’s too, for that matter. Dad ties Sally up, stuffs her in a sack, and drives her back to the murder house in his pickup truck.

Once you get past the almost-normal entry hall, this house is a dead ringer for Ed Gein’s. A sickening profusion of human and animal remains decorate nearly every room, culminating in the attic loft where the mummified bodies of the chainsaw killer’s grandparents repose in a grotesque parody of restful retirement beside the similarly preserved carcass of the family dog. One of the nastier shocks in the movie comes when this clan of loonies assembles for dinner (Sally is tied to a chair at the foot of the table) and it is revealed that the cadaverous old man in the attic is at least marginally alive. Like Sally’s own family, this bunch had earned their living at the slaughterhouse for at least three generations. Now that their ancestral livelihood has dried up on them, they keep the family tradition alive the only way they know how— by waylaying incautious travelers. One assumes that the smoked meat concession the father runs out of his general store does for the meat-processing aspect of that tradition what the ghoulish decorations around the house do for the hide-tanning aspect. The ironic thing is that the sentimentality with which the maniacal family views its slaughterhouse heyday ultimately provides Sally with her avenue of escape. When dinner is over and the time to bring her to the killing floor rolls around, the hitchhiker suddenly gets the idea that Grandpa (John Dugan) should be allowed to do the honors for old times’ sake. He, of course, is far too feeble to strike a real deathblow, and in the confusion surrounding Grandpa’s futile efforts to slay her, Sally breaks free and makes her escape from the house just after dawn. The murderous brothers are in hot pursuit, however, and Sally nearly dies anyway as the hitchhiker catches up to her and begins slicing her back to ribbons with his razorblade. Sally is saved when an eighteen-wheeler comes barreling down the road and crushes her assailant beneath its wheels before the driver can bring it to a stop. That still leaves Leatherface and his chainsaw, but he too is foiled when another driver arrives on the scene and picks up the severely wounded Sally while Leatherface struggles with the trucker. The movie then comes to an abrupt halt, its only resolution the vague hint in the opening narration that the killers were eventually brought to justice.

Because The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is a likely candidate for the title of the first full-fledged American slasher movie, I find it very interesting how little of this film wound up being recycled when the US slasher boom began in earnest six years after its release. Beyond its all-youth cast of protagonists and the unusual weaponry employed by its villains, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre has actually contributed almost nothing to the currently accepted template. Gunnar Hansen’s portrayal of Leatherface as more monster than man can be seen as an antecedent of Halloween’s Michael Myers, I suppose, but he lacks what seems to me to be the latter character’s defining trait, his inhuman resistance to physical injury. True, it seems to bother Leatherface less than it would you or me when he accidentally gashes his own thigh with the saw during the climactic chase scene, but this is the only time in the movie when the killer is hurt in any way, and the damage is nothing an ordinary man couldn’t walk (or at least limp) away from. Meanwhile, the multiple killer angle is virtually unheard of in subsequent slasher films (Hell Night is the only other example I can think of off the top of my head), the endemic take-off-your-clothes-and-die syndrome is conspicuously absent, and the usual slasher-movie plot structure takes on drastically different proportions here. Whereas both the gialli and the post-Halloween American slasher flicks tend to winnow out their Expendable Meat characters in a gradual and methodical manner, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre bumps off Kirk, Pam, Jerry, and Franklin in a shockingly brief span of time, and does so with almost no fanfare; Kirk’s death in particular is striking for its *whack!*— “Next!” quality. The result is that the movie’s Final Girl sequence— to which most slasher flicks both before and after devote ten or maybe fifteen minutes— ends up consuming fully a third of the film. With more than half an hour to fill, Sally’s travails at the hands of the killers become truly harrowing in a way that few other films of this type have even approached, and I can’t think of even a single other slasher movie that subjects its heroine to such sheer physical brutalization before finally granting her the expected reprieve.

The ghastly amount of damage inflicted on Sally over the course of her night in the family’s clutches is only the most shocking and attention-grabbing aspect of what might be the biggest difference between The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and the spawn of Friday the 13th— its unflinching, singleminded harshness of tone. There is no wacky practical joker here, no shower scene or equivalent cheesecake interlude. Hell, with Jerry’s death coming as early as it does, there isn’t even the chance to trot out the sort of perfunctory romance subplot that one so often encounters in cheap horror movies. There are a few 80’s slasher flicks that follow this movie’s lead here— like Maniac and its tiny handful of imitators (Don’t Go in the House, for example)— but the subsequent film that most closely matches the feel of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is one that I wouldn’t be comfortable including within the slasher subgenre at all: the other great American cannibal opus, The Hills Have Eyes. Part of it has to do with the similarities between the two movies’ settings and subject matter, of course, but what ties The Texas Chainsaw Massacre to The Hills Have Eyes most closely is the complete absence of the sense of safety one usually gets while watching an American horror film. Tobe Hooper takes as few prisoners here as Wes Craven would three years later, and taking in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is so discomfiting an experience that I’m not a bit surprised that many viewers come away with the impression that it is far more graphically violent than is actually the case.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact