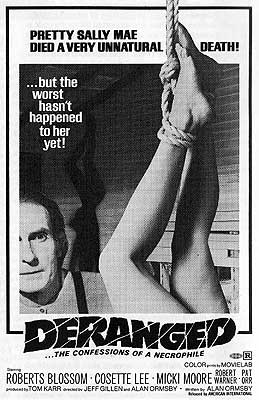

Deranged / Deranged: The Confessions of a Necrophile (1974) ****

Deranged / Deranged: The Confessions of a Necrophile (1974) ****

Ed Gein was horrifying on at least two levels. The first, obviously, was the part where he dug up a bunch of corpses, killed a bunch of people, ate parts of them, and used the rest to create what in later years might have become the stock for the world’s ghastliest Etsy store. But just as frightening in its way is what Gein did in the mental hospital where he spent the second half of his life— which is to say, nothing. By all accounts, Gein was quiet, polite, cooperative, and all around just about the least troublesome cannibal killer a psych-ward orderly could want. It doesn’t compute. People who do what Gein did aren’t supposed to say “yessir” and “no ma’am.” They’re not supposed to hold doors for little old ladies or practice correct hat etiquette. They’re not supposed to bother with “God is great, God is good, and we thank him for our food.” If someone’s going to be a monster, they should at least have the decency to act like one! So maybe it isn’t surprising that most of Ed Gein’s cinematic doppelgangers have been more conspicuously aberrant in their personal demeanor than the actual article. Jame Gumb in The Silence of the Lambs is a secret smartypants, with his night-vision goggles, his lavishly appointed and strategically designed murder basement, and his high-tech ranch for Southeast Asian moths. He may not be on Hannibal Lecter’s level, but he’s got layers and layers and layers beneath his façade of dim bumpkinry. Leatherface from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre goes to the opposite extreme, scarcely even qualifying as human. And even Norman Bates, the most unassuming Hollywood Gein knockoff, has that serpentine Mother persona he withdraws into during Psycho’s final scene. You just know changing his bedpan is a short-straw chore among the staff of whatever Arizona loony bin that’s supposed to be at the end there. Deranged is different, though. Alone among the Gein-derived fright films I’ve seen, it fully exploits the horror inherent in a man of dull-normal intelligence, embodying a recognizable if weirdly old-fashioned version of homespun country values, being also the kind of guy who digs his mother up from the cemetery and stuffs her. The quietest and most low-key picture of its kind, Deranged is also the most haunting. Whereas Psycho and The Silence of the Lambs wow you with their technical prowess, and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre leaves you gasping and drained from the savagery of its assault, Deranged produces a lingering unease that none of its more famous fellows can match.

Deranged begins by punching the “based on a true story” button extra-hard, claiming that only the names and locations have been changed. That’s a lie as usual, but Geinecologists will note that it turns out to be a much smaller lie than one normally expects. Then we meet Tom Sims (Leslie Carlson, from Deadly Harvest and Videodrome), the newspaper reporter who supposedly broke the story of the Butcher of Woodside, and who will intrude from time to time throughout the film to narrate us over some rough patches in the tale. The first time, Sims serves as the Voice of Exposition, introducing us to poor farmer Ezra Cobb (Christine’s Roberts Blossom) and his ailing mother, Amanda (Cosette Lee). Amanda had a stroke twelve years ago, which paralyzed her from the waist down, and now I’m pretty sure she has stomach cancer. On the night of her death, Amanda has a mouthful of parting advice for her son, virtually all of it having to do with what a bunch of no-good, conniving, sex-mad bitches women are, and how the only one he might be able to trust is a middle-aged widow she knows, by the name of Maureen Selby (Marian Waldman, of Black Christmas and When Michael Calls). Mama figures Maureen is too fat to go whoring around with any great success, and she knows Maureen doesn’t drink alcohol. But whatever he does after Amanda is gone, Ezra must always remember that the wages of sin are “gonorrhea, syphilis, and death!” Not the cheeriest note to go out on, but then something tells me cheer was never a big part of Amanda Cobb’s repertoire.

Ezra gives up farming his own land after his mother’s funeral, supporting himself instead as a freelance handyman doing odd jobs for his fellow Woodsiders. Naturally his most frequent customers are his next-door neighbors (which is to say that they live only about three quarters of a mile away), the Kootzes. Indeed, Harlon Kootz (Robert Warner, from The Cult and Octaman) becomes about the closest thing Ezra has to a real friend. No one can replace Cobb’s mother, though, and his grief grows steadily deeper, weirder, and more obsessive until one night, acting upon commands from bad dream, Ezra sneaks off to the cemetery to open Amanda’s grave and bring her home. Mind you, she’s not in the best shape after a year under the ground, so Ezra has some work to do fixing her up. He reads up on taxidermy and experiments with everything from fish skin to cotton batting, but enjoys dishearteningly little success until Harlon inadvertently sets him on the right track. Ezra has never really cared what went on in the world beyond his farm, so he’s also never read more of a newspaper than could be captured by a cursory glance at the front page. Consequently, he’d never heard of an obituary before the morning when Kootz shows him the one for his mother’s old friend, Mrs. Johnson. Suddenly it hits Ezra. With these obituary things, he could find out to the day whenever a fresh body goes into the graveyard— fresh enough to be useful for whatever repairs Mama might need! He skedaddles to the cemetery that very night, and returns home with Mrs. Johnson’s head. The flesh of her face supplies patches for the most badly decayed parts of Amanda’s, while her skull goes onto one of Mama’s bedposts so that she’ll have someone to keep her company while Ezra is out of the house. As the months go by, Ezra makes more trips to the boneyard, until eventually there’s a veritable quilting bee of mummified old dead gals hanging around the Cobb property.

It’s possible that matters would have progressed no further than that had Jenny Kootz (The Reincarnate’s Marcia Diamond) not gotten it into her head that Ezra needed more of a social life than she and her family could provide. But the day soon comes when Jenny spreads a little asphalt on the road to Hell by suggesting that her neighbor ought to get himself hitched. Ezra is skeptical at first— gonorrhea, syphilis, and death, remember— but then he recalls Mama vouching for Maureen Selby. Ez goes a-courting, and Maureen proves remarkably open to his advances, fumbling and hesitant though they may be. What really does it for her is when she sees that Ezra is dead earnest when he speaks of talking to his mother even now. Maureen still talks to her late husband, too, which is why everyone in Woodside who doesn’t dismiss her as a fat pig dismisses her as a loony-bird instead. The pair’s first date is to be a dual séance at Maureen’s apartment, but it goes badly for all concerned. When Maureen begins channeling her husband, the dead man insists that Ezra take her into the bedroom at once and “make her a woman again.” Ezra knows what Mama would say to that, and the date concludes with him shooting Maureen to death in her own bed.

The murder of Maureen Selby initiates a new phase in Ezra’s psychological disintegration, in which his newly awakened libido goes to war against the prudish misogyny instilled in him by his mother. The result is invariably deadly for any female who catches his eye. Ezra’s next victim is a barmaid called Mary Ransom (Micki Moore, from The Vindicator and The Believers), who works at Goldie’s Tavern. Under-socialized as he is, Ezra is unable to distinguish between the pose of professional flirtatiousness which Mary adopts while on the clock and genuine romantic or sexual attraction. You can imagine how he reacts to discovering there’s a difference. Then comes Sally (Pat Orr), the new girlfriend of Harlon’s teenaged son, Brad (Brian Smeagle). Sally is quite simply the most beautiful girl Ezra has ever seen, and he’s not about to let the age difference between them, the fact that she’s already spoken for, or his own close personal ties to the guy doing the speaking stand in his way.

The main writer of Deranged was Alan Ormsby. If that name sounds familiar, it might be because we’ve encountered him before around here as the writer and star of Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things. I have a significantly higher opinion of that movie than most people, but even so the improvement between it and Deranged is simply astonishing. Orsmby already proved himself an astute observer of psychology in Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things, but that time around he did so within what was obviously his native social milieu, and his script had little merit apart from that. In Deranged, Ormsby shows that he could see just as keenly what makes practically anyone tick, and that he could translate that perception into a story with readily understandable stakes and a bit of forward momentum. Let’s put Ezra Cobb himself aside for the moment, and look at how vividly Ormsby sketches the supporting cast— none of whom get a lot of screen time. Amanda Cobb, I grant you, is pretty much a cliché, the dour Fundamentalist anti-sex fanatic. Just the same, though, Ormsby both makes her an internally consistent cliché, and allows her enough idiosyncrasies to feel believable as an individual person. Maureen Selby, on the other hand, is an extraordinary creation, uniting bathos, tragedy, sensitivity, and a mental illness almost as repellant in its way as Ezra’s own. The séance scene— especially the part where she supposedly channels her husband— manages to be eerie, funny, psychosexually skin-crawling, and achingly sad all at the same time. Mary Ransom is pretty straightforward in comparison, but I’m impressed nontheless with how unequivocally Orsmby (and Micki Moore, to give credit where it’s due) establishes what Ezra is unable to see, that Mary’s demeanor at Goldie’s is an act that she puts on as part of her job. Considering what happens to her because of it, it’s vital that we see how completely Cobb has the wrong idea about her. Finally, consider the Kootzes, who don’t look like much, but are crucial to the functioning of the film. Their role is to dramatize and to render intelligible how an Ed Gein type can go undetected even in a community where everyone knows everyone, and is constantly all up in each other’s business. On at least three occasions, Ezra essentially confesses to Harlon what he’s doing, or is planning to do, but Kootz fails to grasp the significance. Either he takes Ezra’s confession as a bizarre joke, or he attributes to it some other meaning based on Cobb’s status as the town eccentric. But when Ezra abducts Sally, Brad Kootz understands at once who is behind the girl’s disappearance. Unlike his father, Brad recognized all along that Cobb was crazy. Brad’s just a kid, though, so he lacks the standing to render such a judgment against one of his elders except in the direst emergency. Between polite silence, deference to adult authority, and willful obliviousness, a guy like Ezra Cobb can get away with a lot.

Ezra, of course, is the true triumph of Deranged, but the laurels for him belong less to Ormsby, I think, than to Roberts Blossom. Deranged is practically a one-man show for much of its length, and frankly I’m at a loss to understand how this performance didn’t make Blossom the most sought-after portrayer of aging oddballs in the business. Just watch the scene in which Ezra reports to Mama’s corpse on his first meeting with Maureen, and allows as he’s not altogether sure the gal’s elevator goes all the way to the top floor. (It’s the talking to spooks that has Ezra concerned. Mama’s a different story, you see— she’s a mass-having, space-occupying corpse, so Ez knows she’s got to be real!) That scene is a miniature masterpiece of both understated psychological horror and deadpan black comedy, and it’s just one of the treasures Blossom lays at our feet here. He can be an adroit straightman, as when he cycles through an indescribable array of facial expressions in response to Maureen’s revelations about her continuing relationship with the departed Eric. He can play a pitiable man-child, as we see when Ezra falls in love with Mary’s public persona in spite of all Amanda’s advice to the contrary. He can do wily menace, like during Ezra’s campaign to steer the barmaid into his clutches. And he can be downright terrifying, too, like when Ezra springs his trap on her at last, rising from among his collection of mummified grannies, masked with one of their preserved faces. Sure, Blossom got plenty of work between Deranged and his retirement from the screen at the turn of the century, but he deserved the kind of career that generates fandoms. On the basis of Deranged alone, people ought to speak of him in the same breath as Ken Foree and Angus Scrimm.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact