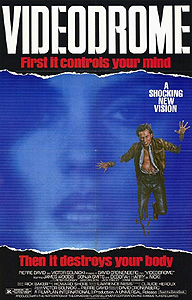

Videodrome (1982) ****

Videodrome (1982) ****

Robert Pattinson was on “The Daily Show” the other night, ostensibly to talk about his latest project, the forthcoming David Cronenberg movie Cosmopolis. At one point during his seven-minute chat with host John Stewart, Pattinson said that he thought it was “physically impossible” to explain what the film was about. I was not a bit surprised to hear that. It may not be as obvious a recurring theme of Cronenberg’s work as medical or venereal horror, but it surely is a marked tendency of his to make movies that forcefully resist reduction to a simple statement of premise. Sometimes (and I gather that this is what Pattinson was getting at with regard to Cosmopolis), that resistance stems from the film’s meaning being located far from its nominal plot. But more frequently, a Cronenberg movie will defy explanation because the viewpoint character’s perspective is so unreliable that it becomes difficult to say for certain what the nominal plot is in the first place. In these films, what the camera shows us is plainly not to be trusted, for what it’s showing is the perceptions of a disordered mind. So far as I’ve seen, Videodrome was Cronenberg’s first serious employment of that technique. Its protagonist spends most of the running time suffering from a hallucinogenic brain tumor, and it would be a mistake to believe anything he sees too uncritically.

The aforementioned protagonist is Canadian independent television producer Max Renn (James Woods, from Cat’s Eye and Vampires). His station, CIVIC-TV Channel 83, is a conduit for all manner of underground video weirdness, as if “Night Flight” had expanded to consume the USA Network’s entire programming schedule. Channel 83 broadcasts pornography as well as extreme horror and action films (Videodrome may be set in an unspecified near future without government censors or Standards and Practices departments, or perhaps Canadian TV in the early 80’s was much less strictly regulated than I would ever have imagined), but Renn’s ace in the hole is his background in the field of pirate television. He still has ties to that scene, and whenever he or his top technician, Harlan (Peter Dvorski, of The Dead Zone and The Kiss), sees something especially riveting on the illegal airwaves, Renn uses those connections to track down the responsible parties, and offers them a deal with CIVIC-TV. It is thus fair enough to say that there’s no other station in North America quite like it.

Channel 83’s programming and business practices have made Renn something of a lightning rod for media criticism, naturally, and we get to see as much for ourselves when he appears as a guest on the daytime talk show hosted by Rena King (Lally Cadeau, from Threshold and Rats). The other guests during Renn’s segment are radio call-in psychologist Nicki Brand (Deborah Harry, of Anamorph and Tales from the Darkside: The Movie) and self-proclaimed “media prophet” Brian O’Blivion (Jack Creley, of Rituals and The Reincarnate)— the latter of whom surreally appears remotely, via a TV set mounted on the “Rena King Show” soundstage, due to some crackpot vow never again to be seen on television except on television. King attacks Renn for contributing to the coarsening of culture and public discourse. Renn retorts that he is providing a necessary service by externalizing, and thereby exorcising, society’s collective id. Brand dismisses that claim as glib bullshit, and turns the conversation toward addiction to sensation, citing herself as a bigger sensation addict than practically anybody. O’Blivion spouts bewildering non-sequiturs about a rapidly approaching future in which everyone will have a telecommunications presence, and in which our self-created telecom lives will be realer and truer by far than our socially constrained material ones. Max comes on to Nicki, offering to service her addiction (nudge, nudge; wink, wink; say no more), and the televised discussion begins breaking down into chaos.

Let’s talk some more about Harlan, though, because he’s really the one who gets this movie started. Among Harlan’s regular duties is to monitor the global airwaves with Channel 83’s high-sensitivity receiver dish, searching for traces of unlicensed broadcasts. One afternoon, he shows Max something that he says he picked up just for a moment before an ingenious scrambling system reduced it to static. It’s called “Videodrome,” and it appears to be a fetish-porn program of sorts. What Harlan was able to record shows a nude Asian woman bound in an austere, cell-like room, being tortured by robed and hooded figures. There’s no hint of a story, no editing or camera maneuvers, nothing to suggest to the untrained eye that it is anything more or less than the documentation of a sex crime in progress. Renn’s eye is not untrained, however, and to him, the very artlessness of Harlan’s brief “Videodrome” clip indicates a sophisticated hoax— which is to say, something Channel 83 could potentially use. He asks Harlan to pin down the source of the transmission, and to see if he can’t find some way to decrypt the signal so that they can evaluate the program more systematically. Harlan comes through on both counts, and when Renn sees his first complete “Videodrome” broadcast, he becomes a little obsessed with bringing the outlaw S&M show into the CIVIC-TV fold. Now if only he knew any TV pirates in Pittsburgh, which Harlan identifies as the signal’s point of origin…

Renn makes his first try through a friend of his named Masha (Lynne Gorman), from whom he often buys glossy soft-smut pieces for his station. She knows people in Pittsburgh, but all she’ll tell Max after doing a bit of reconnaissance on his behalf is that “Videodrome” is nothing he wants to mess around with. According to Masha, the people behind “Videodrome” are dangerous, because unlike Renn, they have a philosophy directing their activities. Max can drag but one more bit of information out of her: evidently that Brian O’Blivion nutter from “The Rena King Show” is connected to “Videodrome” somehow. That leads Max to visit O’Blivion’s “charity,” a big but dilapidated storefront operation downtown called the Cathode Ray Mission. O’Blivion won’t see him— O’Blivion never sees anyone— but his daughter, Bianca (Sonia Smits, from The Pit and TekWar), suggests that if Max leaves a message with her, the prophet might deign to reply via one of his signature video monologues. Oddly enough, Renn’s best chance of getting in touch with the “Videodrome” masterminds might actually be Nicki Brand, although that’s an angle he’s more than reluctant to play. Nicki and Max have fallen into a rather odd affair, and when he shows her the tape Harlan made, she decides that the best way to quiet her sensation jones for a while is to go to Pittsburgh and audition for the part of the victim in a future “Videodrome” telecast. Max is horrified. Despite what he continues to say to the contrary, he increasingly suspects that the torture portrayed on “Videodrome” is real, and that he and Harlan might even have stumbled onto a uniquely fearless snuff film racket. Nicki just takes it as a challenge when he tells her that.

Max has it all wrong, though— or at least he has most of it wrong. “Videodrome” is indeed a conspiracy with aims far larger than giving the finger to the Federal Communications Commission, but the images it broadcasts, however disturbing or criminal they might be, are really beside the point. This intelligence comes straight from the top, for Max’s snooping and prodding have not gone unnoticed. Not long after Nicki takes off for Pittsburgh (and goes worrisomely incommunicado), Max receives a videotaped missive from Brian O’Blivion. He also receives a summons from someone calling himself Barry Convex (Leslie Carlson, of Black Christmas and Deranged), and between the two, Max learns at last what he’s really uncovered. O’Blivion claims to have created “Videodrome”— or at any rate, its hidden essence— while Convex purports to be the current head of the project. The latter would like to meet with Renn after hours at the Spectacular Optical eyeglass shop that serves as the front for his newly launched Canadian operation, which Max is happy to do no matter how shady that sounds, because watching O’Blivion’s tape seems to have done something to his mind. Not only did the video message bring on powerful hallucinations and vivid nightmares, but similar visions have dogged him ever since, both waking and asleep. If Convex can explain what that’s about, then Renn will talk to him in whatever skanky-ass deathtrap he pleases.

Convex informs Renn that O’Blivion’s tape isn’t his problem— Harlan’s is. The psychedelic properties of the “Videodrome” broadcast come from an encoded signal, a technology which O’Blivion helped develop, but lacked the skill to bring to full maturity. Truth be told, Convex and his people don’t quite have all the kinks worked out yet, either. The “Videodrome” signal induces growth and change in a particular sector of the brain, which in turn brings on hallucinations and a quasi-hypnotic state in which both the visions and the subject’s behavior can be programmed by suggestion— either auto-suggestion or direction from outside. O’Blivion hoped to use the process entheogenically (thus the Cathode Ray Mission), as the first stage in a vague sort of post-humanist revolution. It was rather inconvenient, then, that the ganglia thus mutated had a way of turning malignant, so that death was the price of enlightenment. For Convex’s purposes, however, the lethal side-effects were an absolute boon. Convex believes that Western civilization has entered a decadent phase in which it will be vulnerable to competition from the rest of the world, which has been toughened by the very adversities that the West has spent the last century trying to eradicate. Well, what better way to combat decadence than by hiding O’Blivion’s brain cancer rays inside video entertainment tailored to the tastes of the decadent— especially if those rays will also turn the recipient into a programmable zombie during the early stages of the tumor’s growth? Ever since Convex came to that realization, a Scanners-like secret war has raged between his followers and O’Blivion’s, with the former pulling slowly but inexorably ahead. Convex is just about ready to conduct the first full-scale test of the “Videodrome” system, so it’s awfully nice of Renn to come forward right now with exactly the means necessary to carry it out. Max may no longer wish to participate now that he knows what “Videodrome” really is, but no matter. If Renn is having the hallucinations, that means he’s already had sufficient exposure to be susceptible to hypnotic mind control. What Renn wishes is no longer of consequence to anyone but Renn.

Here’s your controlled dose of MIND BLOW for the day: Brian O’Blivion was right. Sure, he flubbed a couple of the details. I mean, outlaw television was always too capital-intensive to be viable as a mass movement, and most people don’t watch even legit TV over the airwaves anymore. Videotape, meanwhile, requires a physical distribution chain (striking at the heart of O’Blivion’s more mystical teachings), and is limited by technical constraints like format compatibility (tellingly, every videotape we seen in Videodrome is a Beta cassette), generation loss, and tape wear— and if you consider for a moment the postage cost of a videotape mass mailing, the capital overhead becomes only slightly less daunting over time than that associated with pirate transmitters. But if we look at the substance of O’Blivion’s claims, divorced from their early-80’s technological context, a very familiar picture emerges. Telecommunication for everyone who wants it (or at any rate, radically democratized access to the means of telecommunication)? The decoupling of identity from face-to-face social interaction, freeing people to become whoever or whatever they wish to be seen as, even if that means maintaining multiple simultaneous selves— or indeed no externally recognizable self at all? A transformed social reality in which people come to regard the electronically facilitated lives of their invented telecom doppelgangers as more authentic than their “real” lives? Every bit of that has come to pass within the past twenty years; we call it “the internet.”

What makes the eerie accuracy of O’Blivion’s predictions so fascinating is not merely that they came true within a context that just barely existed in 1982. Far more striking is that Cronenberg put forward that vision in a movie that appears totally unconcerned with futurism per se. Videodrome is only superficially a work of speculative fiction; at heart, it’s a “horror of madness” story in which individual madness is both causative and symptomatic of the madness of whole civilizations. People in Videodrome are diseased because their cultural environment is diseased— but how can a culture created by the diseased possibly be otherwise? Even more than in the post-humanist nightmare world of Renn’s hallucinations, the horror of Videodrome lies in how little anyone seems to be able to do about this grim state of affairs. Nicki Brand tries to treat the individual madness of others while embracing her own, but doesn’t look to be enjoying much success on either front. On the one hand, her “patients” encounter her only through the alienating interface of a telephone switchboard, and their therapeutic needs— privacy, personalization of treatment, the psychoanalytic insight that comes only through prolonged acquaintance between clinician and subject— are self-evidently at odds with the requirements of a popular radio show. And on the other, indulging her hunger for ever stronger stimulation leads her eventually into the destroying clutches of Barry Convex. (Or so it would appear, anyway.) Brian O’Blivion is similarly undone by his attempt to turn society’s sickness to positive ends, and his television utopia is ultimately no less dystopic than what it’s supposed to transcend. Max Renn thinks he can exploit the madness all around him, and may even have convinced himself that doing so is noble and important work, but he winds up the exploited instead. And Barry Convex, the only one with the vision to try fighting against the spiral of insanity directly, can conceive of no other way to do it than by becoming a complete monster. Most of Cronenberg’s early movies are bleak, but this is sheer, despairing nihilism! That said, it’s nihilism of a thoroughly engrossing sort, and well worth the bummer that an attentive viewing of Videodrome is sure to bring on.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact