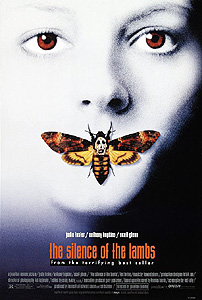

The Silence of the Lambs (1991) *****

The Silence of the Lambs (1991) *****

1981 saw the initial publication of Red Dragon, the second novel from journalist and sometime suspense author Thomas Harris. A major departure from its predecessor, the terrorism thriller Black Sunday, Red Dragon was an unusual police procedural focusing on the FBI’s then-recent innovation of using psychological profiling to catch serial killers. The novel was a moderate success— enough to make Dino De Laurentiis option the rights to a film adaptation, but not enough to give him any qualms about changing the title to something he thought sounded more marketable. When the Red Dragon movie appeared in 1986, it did so under the name Manhunter; the new moniker must not have been as enticing as De Laurentiis thought, however, because nobody much cared. Manhunter deservedly won a coolly favorable reception from critics, but audiences proved a tougher sell, and the film grossed less than half of its reported production cost. So complete was the fiscal disaster that when Harris wrote a sequel to Red Dragon two years later, de Laurentiis supposedly gave away his movie option on The Silence of the Lambs (to which he was apparently entitled under the terms of the Red Dragon/Manhunter deal) literally for free to Orion Pictures. One can imagine Dino’s horror when Orion’s The Silence of the Lambs became one of the biggest hits of 1991, and went on to sweep all five of the top-shelf Oscar categories— this despite the fact that the source novel was little more than a rewrite of Red Dragon with the psychically damaged retired-cop protagonist switched out in favor of a bright, young, female cadet. By any measure, The Silence of the Lambs was a tremendous achievement, the kind of thing that redefines people’s careers. Overnight, Anthony Hopkins went from being that sort of difficult guy who makes sort of difficult movies about people stifling their emotions to being among the hottest middle-aged stars in the business. Jodie Foster suddenly had all of America taking her nearly as seriously as John Hinkley did. And Jonathan Demme— producer of The Hot Box, scenarist of Black Mama, White Mama, director of Caged Heat— was now the highest-profile graduate of the Roger Corman Academy of Film since probably Francis Ford Copolla. Everybody involved deserved a meteoric career upturn, too.

Clarice Starling (Foster, also in Contact and The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane) is among the most promising cadets in her class at the FBI academy in Quantico, Virginia. She has impressive scholastic credentials, a razor-sharp mind, and mountains of drive and ambition. Specifically, she wants to enlist in the Bureau’s Behavioral Science Division, under the leadership of ace detective Jack Crawford (Scott Glenn, of Gargoyles and The Keep). Imagine her excitement, then, when Crawford sends word that he wants to see her in his office about a special assignment. Naturally, the first thing one needs in order to create usable psychological profiles for criminal types is a great deal of raw data on the habits and personalities of the criminals whose behavior you wish to analyze and predict. Crawford has plenty, but there’s one particular psychopath he’d dearly like to add to his collection, and the man in question has thus far resisted all his best efforts. His name is Hannibal Lecter (Hopkins, from Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Audrey Rose), and he used to be one of the Baltimore-Washington area’s top psychiatrists; now he’s in a mental hospital himself, having developed an appalling habit of killing and eating his patients. That combination of brilliant shrink and almost inhuman psycho is practically unheard of, and it isn’t hard to see why Crawford would consider Lecter such a prize. Nor is it difficult to imagine why Crawford would think that Starling— herself an accomplished student of the human mind, and an extremely pretty young woman to boot— could be the tool that finally allows him to pick Hannibal the Cannibal’s brain. Starling jumps at the chance to impress her professional idol, and hits the road for Baltimore at the earliest opportunity.

This is a very different Hannibal Lecter from the one nobody particularly remembers in Manhunter. To begin with, there’s the cannibalism thing. The earlier movie never said anything about it, and in Harris’s old novel, there is considerable reason to suppose that it was all bullshit anyway, an embellishment dreamed up by a Chicago-based tabloid newspaper. This time, though, Lecter is an admitted and completely unapologetic consumer of human flesh. The revised characterization also includes preternaturally acute senses, an eidetic memory, and such ophidian serenity that he is able to chew off a nurse’s face without elevating his pulse rate above 85 beats per minute. That last bit of nastiness is conveyed to us (and to Starling) as part of a warning address from asylum director Frederick Chilton (Deep Rising’s Anthony Heald), delivered— with visual aids, no less— while he’s leading the cadet down to the maximum security ward where Lecter is kept. The tone of Starling’s meeting with Lecter is odd, to say the least. It’s almost like a job interview, with the deranged shrink grilling Starling to decide whether she’s worthy of his time and attention. Lecter doesn’t seem to give a rat’s ass about Crawford’s questionnaire, but he’s very interested in Starling herself, pressing her with exactly the sort of personal questions Chilton expressly warned her not to answer. He also shows an unusual interest in the “Buffalo Bill” case. Bill is the serial killer Crawford’s unit is currently hunting; his nickname was bestowed by the Kansas City cops who found the partially flayed bodies of his first few victims, and observed that this guy “likes to skin his humps.” Lecter’s curiosity gives Starling the idea that maybe he knows something about the other killer, and she attempts to steer the conversation in that direction. All she gets out of him, though, is the first of what will eventually become a great many cryptic hints: “Look deep inside yourself, Agent Starling, and seek out Miss Mofet— M-O-F-E-T.”

So how smart is Clarice Starling? Smart enough, for one thing, to be suspicious of that “look inside yourself” bullshit, and to figure out that she’s supposed to hunt down this Mofet person at the Your Self Storage Center outside of Baltimore. Starling is very surprised at what she finds inside the shed rented in Hester Mofet’s name— an antique limousine with a dolled-up severed head in a jar full of alcohol on the back seat! That’s about when Starling notices that “Hester Mofet” is an anagram for “The Rest of Me.” Another visit to Lecter clarifies the situation somewhat. The head in the shed belonged to Benjamin Raspail, a former patient of Lecter’s, but not one of his victims. Lecter claims not to know who killed the man, but it amused him to cover up the crime. He also off-handedly suggests that Raspail’s head was made up like an aging hooker as part of “a fledgling killer’s first attempt at transformation.” It would appear that the whole business has been a test of Starling’s deductive acumen, one which she has passed with flying colors. And now that Lecter knows he’s dealing with someone who meets his exacting standards, he offers Starling a partnership of sorts. The doctor knows perfectly well that he’s a lifer, but he wants very badly to have something else to look at than Chilton’s smirking face and these same four cinderblock walls. If Jack Crawford can pull a string or two and get him transferred to someplace with a window and a tree, Lecter will grant Starling the benefit of his vast intelligence and expertise in bringing Buffalo Bill to justice. It would be a hell of an opportunity for an ambitious young agent.

That, as it happens, was Jack Crawford’s thinking, too. Knowing full well how much Lecter likes to play games, and being equally well aware of Starling’s thirst for advancement, he brought the two of them together precisely in the hope that some such bargain might be forthcoming. Indeed, the only reason he didn’t tell Starling about it up front was because he knew Lecter would have been able to sniff out any ulterior agenda in a matter of minutes— better to let Lecter believe the collaboration was his own idea, even if doing so meant manipulating Starling just a little. But now that she’s got her in with the doctor, Crawford can pull Starling right into the thick of the investigation. He brings her along when the police in Elk River, West Virgina, fish another partially skinned dead girl out of the river, and Starling is the one who notices the strangest clue to surface yet: somebody stuffed an insect chrysalis down the victim’s throat before dumping her body. A trip to the Smithsonian Institution’s Insect Zoo reveals that the pupating bug is an Acherontia styx— a Malaysian death’s-head moth. They’re not found wild in the Americas, and they don’t breed in captivity, so somebody went to a lot of trouble to get this one. One obviously doesn’t import Southeast Asian caterpillars without creating a paper trail, so the moth represents a solid new lead to track down. But perhaps more importantly, the cultural symbolism of the lepidoptera seems to tie in with something Lecter said during his second meeting with Starling. What was that business about Raspail’s head representing an early attempt at transformation? Was he implying that Buffalo Bill killed Raspail? That would certainly explain why forensics finds a death’s-head moth tucked away inside his mouth, too.

Meanwhile, Crawford’s pursuit of the killer is about to become a lot more urgent. Right outside her Memphis home, Catherine Martin (Brooke Smith, of Series 7: The Contenders), daughter of Senator Ruth Martin (Diane Baker, from Strait-Jacket and The Haunted), offers to help a man with his arm in a cast load a loveseat into the back of his van. Once he has Catherine inside the vehicle with him, the man (Ted Levine, from The Mangler and the Hills Have Eyes remake) smashes her on the head with his cast, strips off her blouse, and makes a close examination of her skin before tying her up and driving away with her. Catherine— tall, big-boned, a bit on the chubby side— is exactly the sort of woman Buffalo Bill favors as his victims, and the torn blouse he leaves behind at the abduction scene has also become something of a trademark of his. Word that a senator’s daughter has fallen into the killer’s hands turns up the heat on Crawford considerably; if Buffalo Bill’s pattern to date holds true in the current case, then there’s about a three-day window of opportunity in which the FBI might catch him before he slays and skins Catherine Martin. Recognizing, on the basis of his “transformation” comment, that Lecter almost certainly knows who Buffalo Bill is, Crawford sends Starling back to Baltimore with a phony offer from the senator, promising to have him transferred to a federal institution in New York State if his information leads to Buffalo Bill’s capture while Catherine is still alive. It’s an excellent strategy, and Lecter is taken in by it, but then that glad-handing asshole Chilton goes and fucks up everything. All along, Dr. Chilton has resented having to sit on the sidelines while some kid who isn’t even out of the academy yet conducts lengthy interviews with one of his patients— and he really resents the fact that the patient in question happens to be one who openly considers Chilton himself a fool. Chilton eavesdrops on the conversation when Starling makes her bogus offer, and he immediately calls Senator Martin to check up on the story. Seeing an opportunity to make himself the center of attention, Chilton cuts a deal of his own with the senator, its terms being roughly comparable to those “offered” by Crawford and Starling. There are, however, a few major logistical differences, calculated to give Chilton a chance to play hero in front of the media, and it is there that we find the danger for Crawford, Starling, Chilton, Catherine, Senator Martin, and really just about everyone else even tangentially connected to the Buffalo Bill-Hannibal Lecter case. Chilton, you see, really is a fool…

Truth be told, The Silence of the Lambs really shouldn’t work anywhere near as well as it does. One villain is, at best, a background presence for the first two thirds of the film, nearly as unknown to us as he is to the police pursuing him. The other spends the great bulk of the movie locked securely inside a plexiglass cage, unable to do anything more harmful than to taunt Clarice Starling about her cheap shoes and her West Virginia accent. 1991 ought to have been far too late for yet another Ed Gein-inspired serial killer to inspire anything more than yawns from horror fans who had, by that time, seen four Psycho movies, three Texas Chainsaw Massacre installments, and who knows how many assorted odds and ends in the vein of Deranged. And as for Hannibal Lecter, how on Earth could anybody take seriously a cannibal psychiatrist who amuses himself by helping the FBI solve crimes, and who possesses not only a photographic memory but also a sense of smell so sharp he can tell you what perfume you decided not to wear today? What we are seeing here, I believe, is the transformative power of total commitment. Nobody involved in making this movie, either behind or in front of the camera, conveys for so much as one second the impression of having approached it with less than complete sincerity, even in its most garish particulars, and that dedication to the cause, when put forward by people of such great ability, leaves the audience with no choice but to go along. Hannibal Lecter is impossible, absurd, but Anthony Hopkins believes in him, and he makes you believe in him too. Buffalo Bill may spend the whole movie in Lecter’s shadow, but Ted Levine shows no sign of either noticing or caring, turning in a performance that could have carried a perfectly respectable psycho-killer flick all by itself. Jonathan Demme directs with a confident understatement that suggests Robert Wise at his best, shrewdly downplaying (except in two key sequences) the idea that this is even a movie at all. The most vital single factor, however, may be Jodie Foster— or, more properly, Clarice Starling.

Starling could very well be the most believable horror or suspense movie heroine of the whole 1990’s. Partly, this is because she is absolutely perfectly cast. Foster had not been Demme’s first (or even second) choice for the part, but she herself had wanted it from before Demme had even begun asking around, and I find it nearly impossible to imagine anyone else in the role— even though Foster declined to return for Hannibal ten years later. Small and slightly mousy despite her considerable beauty, Foster effortlessly looks the part of the scrappy little underdog, and there’s nothing at all California about her bearing or appearance. She also possesses an obvious native affinity for the character, in that her own career has often been a matter of dogged determination in the service of highly individualistic goals. After all, how many other Hollywood stars can you name who made their fortunes playing pubescent serial killers, teenage hookers, atheist astronomers, and women who get raped on top of pool tables? A girl from the West Virginia coal country who wants to hunt psychopaths when she grows up isn’t too much of a stretch in such a context, is it?

What makes Starling such a plum role— and what seems to have made Foster so hell-bent on playing her— has less to do with the qualities of the character per se than with Demme’s and screenwriter Ted Tally’s extraordinary success in presenting the story from her point of view. There are lots of movies with female protagonists in what is normatively a male role, of course, but few that I’ve seen have so subtly and effectively communicated what it would mean to be that woman at the center of the film. The effect is most obvious in the autopsy scene, where Starling first directly confronts the monstrous misogyny of Buffalo Bill, and in a startlingly vile moment involving Multiple Miggs (Stuart Rudin), the inmate in the cell next-door to Hannibal Lecter. The non-obvious instances are the most commendable, however, creating, with a nudge here and a poke there, a powerful sense of the pervasive subliminal pressure that ordinary masculine behavior places on women in male-dominated fields. It comes across in the inept but harmless flirting of the cross-eyed Smithsonian entomologist; in the equally inept and decidedly sleazy passes that Dr. Chilton makes at Starling during their initial meeting; in Lecter’s wry comment that “People will say we’re in love” when Starling comes to see him in Memphis on her own initiative, after she and Crawford have been officially sidelined by Chilton’s machinations; and perhaps most cleverly during a brief moment when Starling finds herself the only woman on an elevator full of male FBI agents, all of them tall enough to carry on a conversation literally over her head. It makes you think in a way that an overtly polemical treatment of the same material would not, and it alters the emotional experience of watching The Silence of the Lambs by adding a nebulous sense of isolation and disempowerment to the more conspicuous strains of flat-out horror inspired by the film’s two serial murderers.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact