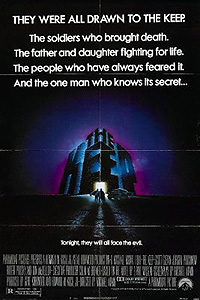

The Keep (1983) *½

The Keep (1983) *½

I can be pretty hard-line about the degree of faithfulness I demand from cinematic adaptations of the written word. I understand that movies, being inherently shorter than books, must necessarily be simpler and more streamlined, but I generally expect a filmmaker who takes it upon himself to bring a novel to the screen to have a solid understanding of how said novel functions, and to be able to identify correctly the essential parts of the story which will permit no tinkering if the adaptation is to be a success. But when the novel being adapted is something as awkwardly structured and poorly thought-out as F. Paul Wilson’s The Keep, I become much more forgiving of wholesale alterations.

As you may already know, The Keep pits Nazi soldiers against a vampire in a Romanian castle, and sees the Germans forced to call upon a Jewish medievalist for salvation. You could do a lot of really fascinating stuff with that premise, and Wilson almost does. But toward the end of the book, he inexplicably turns revisionist on us, and reveals that the creature inhabiting the keep is not really a vampire at all, but rather the quasi-Lovecraftian antique evil from which the vampire legend derives in the first place. There’s nothing necessarily wrong with that, mind you, but the way it’s written gives the impression that Wilson went into The Keep with the a priori intention to give the novel some kind of shocking twist in the final act— any kind of shocking twist— and that this just happened to be the one he came up with when he got there. Wilson’s vampire is far too traditional to be convincing as anything but what he seems at first glance, and the big reveal would ring entirely false even if Wilson hadn’t fumbled so much in the execution. Consequently, when Michael Mann filmed The Keep in 1983, there were two obvious tacks he could take to improve upon the original story. Either he could follow the conventionally Stokeristic vampire premise all the way through to its conclusion, or he could ditch vampirism altogether, and make it plain from the outset that whatever lived in the keep was something bigger, older, and deadlier than a run-of-the-mill bloodsucker. That Mann chose the second alternative probably ought to be expected, given that it freed him from having to invent an entirely new conclusion to the story. Unfortunately, it also imposed upon Mann the obligation to explain to his audience just what in the hell that thing in the keep was, yet Mann’s notorious aversion to exposition made it all but inevitable that he would shirk that obligation almost completely. The result is a visually distinctive and highly memorable film that makes next to no sense unless you’ve read the book— a result which makes next to no sense itself in light of how little of Wilson’s novel beyond the bare skeleton of its plot Mann actually used in the movie.

The place: small village nestled in a pass through the Carpathian Mountains; the time: the autumn of 1941. A mechanized infantry company of the German army, under the command of Captain Klaus Woermann (Jürgen Prochnow, from Dune and In the Mouth of Madness), rolls into town with orders to guard the strategically valuable pass. This particular village has been chosen to host the Wehrmacht garrison because it was built at the foot of an enormous fortified building, which has stood in the pass since God alone knows when, and the high command figures the old keep would make the perfect base of operations for Woermann’s troops. But Woermann, with the practiced eye of a soldier, immediately notices some curious features of his new home that are not apparent from behind a desk back in Berlin. At a distance, the keep certainly looks like a castle controlling the pass. It’s a massive, blocky edifice, constructed of hard, black granite and surrounded by an immensely deep chasm forming a sort of natural moat. But the outer walls slope gently inward toward the roof, and a determined army could easily climb straight up them, even in the teeth of heavy opposing fire. Stranger still, the keep looks to be put together inside out. The stones of which the exterior walls are constructed are small, brick-like affairs, apparently held together solely by friction and collective weight, but the heart of the keep is a sort of gigantic box built of close-fit blocks weighing thousands of pounds apiece, without even a single door or window communicating between its interior and the rest of the castle. To Woermann, it looks as though the place was built not to keep out an army attempting to storm the pass, but to keep some unknown thing sealed up inside it. Alexandru the caretaker (Morgan Sheppard, from Hawk the Slayer and Needful Things) is unable to answer any of Woermann’s questions. His family has looked after the keep since time immemorial, but it was there long before they were. No one knows for certain even who built the thing. What Alexandru can tell Woermann is that it isn’t safe to stay within the keep’s walls after dark; everyone who has tried within his lifetime has been driven out by nightmares fit to drive a man mad.

Given all the mystery surrounding the keep, it is only to be expected that rumors would soon begin circulating among the soldiers regarding just what purpose the old castle was built to serve. Because of its vault-like construction, and the curiously shaped metal crosses— 108 of them— that are set into its internal walls, the rumor mill soon settles on the theory that the keep is a treasure house stocked with fabulous quantities of silver. In fact, some of the men charged with rigging the building with electric lights end up neglecting their duties in favor of trying to pry a few of those crosses from the walls. Alexandru is incensed. For one thing, the crosses are not made of silver, but of nickel. For another, it’s obvious that the otherwise worthless artifacts are closely bound up with whatever superstitions the townspeople have regarding the sinister old building, and Alexandru evidently believes that removing the crosses would be somehow dangerous. Woermann puts a stop to his soldiers’ attempts at looting, and settles into what he thinks is going to be an uneventful routine of watching the pass.

But on what I take to be the Germans’ very first night in the keep, one of the soldiers on night watch makes a discovery. One of the crosses is made of silver after all, and it is set into a block small enough to be shifted by a couple of fairly strong and highly motivated men. The soldier on watch thinks he’s found the route into the keep’s hidden treasure room, and he and one of his partners abandon their largely symbolic posts to have at the silver cross and its movable block. Whatever that impenetrable box at the center of the keep is, it sure as hell isn’t a treasure vault. The shaft through the wall that the soldiers open up leads into a vast, empty space— so vast, in fact, that it hardly seems possible that the keep could contain it. And at the bottom of this abyss, hundreds of feet down the sheer-sided walls, is what looks rather disconcertingly like an ancient European megalith circle. All in all, not quite the heaps of riches that the meddling soldiers had expected. Then, just moments after the man who discovered the silver cross has fully processed what he’s looking at, something takes shape inside the stone circle, and rockets up toward him. The man’s entire upper body simply ceases to exist when the thing hits him, and his accomplice is burned to a smoldering crisp.

Another soldier is killed in the same grisly and preternatural manner on each of the following three nights. Woermann puts in a request to have his unit relocated to someplace safer, but instead of relief, he gets reinforcements. A battalion of Waffen SS, led by Einsatzkommando Stürmbandfuehrer Kaempffer (Gabriel Byrne, of Gothic and Excalibur), arrives at the keep to take control of the operation. Kaempffer has a simple theory to explain the deaths of Woermann’s men. There are communist partisans in the village, and the captain’s lenient touch with the locals has allowed them to go on preying on the soldiers night after night. Kaempffer immediately rounds up and executes five men at random— one for each dead German soldier— and lets it be known that such reprisals will continue on a man-for-man basis “until either the killings stop or I run out of villagers.” Woermann’s protests that Romania is a sovereign state and an ally of Germany do nothing to change the SS major’s position.

The killings don’t stop, of course. And the next time a charred and ravaged body turns up within the keep, it does so beside a scrawled message seemingly melted directly into the stone of the nearest wall. Kaempffer, understandably, is unable to read the graffito, but neither can any of his Romanian hostages. Father Fonescu (Christine’s Robert Prosky), the village priest, tells him that this is because the message is not in Romanian, nor is it written in either the Latin or Cyrillic alphabets. The major is reluctant to believe Fonescu (maybe that’s because, when the camera finally trains on the vandalized wall, we see that the message is written in the Cyrillic alphabet…), but he softens a bit when the priest tells him that he has a friend who used to live in Jassy, a medieval historian, who ought to be able to give Kaempffer a translation. The great irony of the situation is that Dr. Theodore Cuza (Ian McKellan, who has come a long way indeed from here to the Lord of the Rings movies) is a Jew; in fact, he and his daughter, Eva (Alberta Watson, of Virus), are on the train to a concentration camp even now.

Cuza and his daughter aren’t the only outsiders about to pay an extended visit to the keep. At the same moment those two night watchmen stupidly released whatever was imprisoned inside it, a strange young man with lusterless, violet eyes (Scott Glen, from Gargoyles and Angels Hard as They Come) awakens with a start in a Greek hotel room. He instantly packs up everything he has (it isn’t much) and books passage on a boat to Romania’s Black Sea coast, whence he proceeds on to the garrisoned village in the Carpathians. He arrives right about the time that the prematurely aged and deathly ill Theodore Cuza is explaining to Kaempffer that the calling card from his so-called partisans (which reads “I will be free”) was written in the Slavonic tongue, using the Glagolitic alphabet (okay— now that you mention it, there was in fact one Glagolitic character in that scrawl on the wall), neither one of which has been in use for some 500 years.

So, then— let’s have some explanations, or at least as much of an explanation as Michael Mann will allow us. The Cuzas soon meet the thing from the keep, when it saves Eva from being raped by a couple of Kaempffer’s SS pigs by making their heads explode, Scanners-style. The creature— looking like a dense billow of gray smoke with glowing red eyes and brain— carries the unconscious woman to her father’s chamber, where it also lays hands on Cuza and restores his health. Subsequently, Cuza seeks the thing out himself, and the two of them make a deal. If Cuza will dig up a certain possession of the creature’s, remove it from the keep, and hide it in the mountains somewhere, it will exterminate not only the Nazis in the keep, but indeed any Nazis Cuza might care to point it towards. It feels a certain paternal protectiveness toward the Romanian people— even Romanian Jews— and it doesn’t like the sound of the Final Solution. But while that’s going on, Eva has met and fallen in love with the Purple-Eyed Guy, and Cuza might want to hear his take on the situation in the keep before he goes digging up any talismans. Obviously this weirdo isn’t quite human either, and seeing as he neither spent the last five centuries locked up in a supernatural prison nor gradually evolves from a cloud of smoke with a glowing brain into something that looks like a villain from the Japanese “Spider Man” TV show, I’m guessing he’s supposed to be the good guy around here, regardless of how the thing from the keep feels about Hitler and his followers.

This movie ought to have been gripping. Instead, it’s merely baffling. In fact, the strongest impression I took away from The Keep this time around is that it really looks like a good half an hour of footage was cut from the film before its release. What else can we think when Eva seems to fall in love and go to bed with the Purple-Eyed Guy less than an hour after meeting him, or when she has an argument with her dad near the end of the film in which she identifies both of the movie’s supernatural characters by name? Christ— even we haven’t heard what their names are yet! And on the subject of those names, they’re just about the only clue we’ll ever get as to why we ought to be rooting for one supernatural personage over the other— I mean, which sounds more like a villain’s name to you, Molasar or Glaeken Trismegistus? (Glaeken Trismegistus? Say, wasn’t he that guy who always used to hang out at the gym with the Archangel Triton?) Lord knows Molasar’s Nazi-killing track record would otherwise make him seem like a pretty swell guy as far as I’m concerned. We never will learn what he did to get himself imprisoned in the keep, why he seems to like the Romanians so much, or what his real agenda might be now that he’s loose. Nor will Mann ever bother to explain who or what Trismegistus is, or what connection he has either to Molasar or to the keep. Frankly the only characters here whose motivations are at all comprehensible are Cuza and Kaempffer; otherwise, it’s just one great expanse of “Wait— huh?!?!”

Then there’s the acting. With the acting, we may be looking at an even more egregious waste of potential than the story. Anybody whose dominant memory of him is his performance in Das Boot will be amazed at Jürgen Prochnow’s progressively out-of-hand acting here. Even more staggering is the outright awfulness of Ian McKellen, who starts out by giving one of the worst renditions of an old person that any not-old person has ever collected a paycheck for, then apparently moves on to a desperate race to keep his acting always one step more risible than the increasingly silly Molasar suit. You expect some scenery-chewing from the head Nazi, but to see a couple of guys as capable as Prochnow and McKellan matching Gabriel Byrne, overwrought gesture for overwrought gesture, is really sort of alarming. Meanwhile, at the other end of the spectrum, we have Alberta Watson and Scott Glenn, who attack their parts with all the verve of your average Inca mummy. The underacting makes a certain amount of sense for Glenn, who’s supposed to be playing some sort of angel or something, but given that Trismegistus also has to conduct at least a perfunctory romance with Eva Cuza, it ends up doing the movie as a whole more harm than good.

So why is it, then, that so many people who haven’t seen The Keep in many years seem to have such favorable lingering memories of it? My guess is it’s the production design. The look of The Keep is unforgettable— I still can’t quite decide whether it’s deliberately stylized or just too cheap to achieve ordinary realism, but either way, it has the haunting otherness of a half-remembered dream. Sometimes Mann goes too far with his love of slow motion and heavy-handed lighting effects; the final duel between Trismegistus and Molasar wasn’t meant to be hilarious, for instance, but it is. Most of the time, though, the weird editing, too-close camera placement, and overall compositional strangeness works to the movie’s advantage. Hey— something had to, right?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact