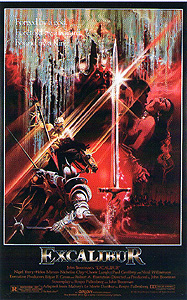

Excalibur (1981) ***½

Excalibur (1981) ***½

John Boorman first began trying to get the legend of King Arthur onto film in 1969. That was the year he went to United Artists with a script called Merlin, and was told, “No. But how would you like to direct The Lord of the Rings for us instead?” There was enough thematic overlap between the two stories as Boorman saw them that he didn’t mind switching from one to the other, and if the latter movie had ever been completed, it would have been visibly informed by the Merlin screenplay, especially with regard to the characterization of Gandalf. Developing the Tolkien adaptation paired Boorman for the first time with Rospo Pallenberg, who would become his favorite writing partner from then until at least the end of the 80’s, but even with two busy brains grinding away at it, the process took so long that by the time they were done, the UA executive whose idea it had been to do a Lord of the Rings movie was no longer with the company. The new regime’s leaders found Boorman and Pallenberg’s script utterly bewildering (not without cause, mind you— everything I’ve read about it indicates an unforgettable fever-dream of a film, and a potential anti-classic of Zardozian proportions). They pulled the plug on the project, but on remarkably generous terms permitting Boorman to shop it around to other studios for a limited time before the rights reverted back to United Artists. The rest of Hollywood deemed Boorman’s Lord of the Rings too expensive to risk, however, and thus it was that we eventually got the dire Ralph Bakshi cartoon instead. Even so, the concepts that Boorman and Pallenberg developed for the Tolkien film didn’t just die. A few found their way into later, unrelated projects (for instance, the sex-magic scene between Frodo and Galadriel is unmistakably echoed in Zardoz, when the women of the Vortex fuck all the amassed knowledge of their doomed civilization into Zed), but for the most part, they went straight into a new, collaborative version of Merlin. Boorman’s standing had evidently risen substantially over the course of the 70’s, even despite Exorcist II: The Heretic, because when he tried again at the end of the decade to interest studios in his increasingly weird Arthurian epic, Orion Pictures took the bait. Their timing was perfect, as it happened. Not only was Excalibur (as Merlin was now retitled) a firm success in its own right, but it also initiated a surge in production of big-budget fantasy movies— and small-budget rip-offs thereof— the likes of which had not been seen since the peplum genre withered up and died in 1965.

Officially, Excalibur is an adaptation of Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur. In practice, though, it samples broadly from several centuries’ worth of mutually contradictory tales and legends concerning Merlin, Arthur, his knights, and the Grail quest, knitting them together more with a mythographic sensibility than with any modern notion of narrative construction. It assumes a lot of a priori knowledge on the viewer’s part, yet at the same time it has no qualms about diverging from what it expects the audience to know. It’s a weird approach, but an understandable one; this movie has miles of ground to cover, and sketchily recombinant reinterpretation was how Malory himself handled the story, anyway.

We begin in “The Dark Ages,” with a war-torn Britain divided among a multitude of petty lords, some of whom harbor ambitions of uniting the country under their singular rule. Of the latter, the most driven is Uther Pendragon (Gabriel Byrne, from Ghost Ship and The Keep), currently embroiled in conflict with the Duke of Cornwall (Corin Redgrave, of The Woman in White and The Turn of the Screw). Uther has a very powerful ally in the wizard Merlin (Nichol Williamson, later of Spawn and Exorcist III), who wants Britain united under one crown for reasons known only to himself. Impressed with Uther’s success in subduing his rivals thus far, and with his personal skill and courage at arms in the struggle against Cornwall, Merlin goes to see an even more mysterious supernatural personage called the Lady of the Lake (Hilary Joyalle), keeper of the magic sword Excalibur. The weapon embodies justice and symbolizes true kingship, and with it in his hand, Uther should be able to silence all rival claimants to the as-yet-notional throne. Certainly Excalibur impresses the hell out of Cornwall and his army when Uther displays it to them on the battlefield the following morning, enough so that the duke concedes defeat and swears fealty to his former rival.

Alas, the new king is a most ungracious winner. At the banquet celebrating the peace, Cornwall has his wife, Igrayne (Katrine Boorman), dance for the entertainment of his guests, and Uther is so overcome with lust that he renews hostilities in the hope of making her his captive concubine. Unfortunately for him, Cornwall and his forces fight twice as hard now that they know what a backstabbing bastard the king is, refusing to be cowed even by Excalibur. When military force does not succeed at once, Uther resorts to magic, demanding that Merlin obtain for him what his army cannot. While a nighttime battle rages away from the ducal castle, Merlin weaves a spell that transforms Uther into Cornwall’s likeness. Uther gets his turn in the sack with Igrayne, and the duke is killed in action right about when the treacherous king orgasms. Awfully convenient for Uther, no? Wizards don’t work cheap, though, and nine months later, Merlin returns to collect his wages for the conjuring— the newborn son of Uther and Igrayne. After initially agreeing to the infernal trade, Uther changes his mind, and rides out to stop Merlin absconding with the baby Arthur. However, before he catches up to the sorcerer, he is ambushed by grudge-holding relations of the duke, and mortally wounded. A spiteful, prideful prick to the last, Uther with his dying breath drives Excalibur into a nearby boulder, signifying that if he can’t be king, nobody will.

Child-rearing is no job for a wizard, of course, so Merlin entrusts Arthur (who will grow up to be Nigel Terry, seen later in feardotcom and Troy) to Sir Hector (Clive Swift, of Raw Meat and Frenzy) for a proper mortal upbringing. Meanwhile, a tradition grows up of periodic tournaments in which knights from all over the land compete for the right to try pulling Excalibur from the stone. Fifteen years or so after Merlin deposited Arthur with Sir Hector, Hector’s biological son, Kay (Rawhead Rex’s Nial O’Brien), goes to participate in one such contest, with Arthur as his squire. It appears, though, that Arthur is somewhat unclear on the concept behind these tourneys, because when Kay’s sword is stolen out of their tent, Arthur tries to make it up to him by giving him Excalibur instead— which he has no trouble freeing from its rocky prison.

The range of reactions to Arthur’s thoughtless feat is neatly defined by Leondegrance (Patrick Stewart, from Lifeforce and Star Trek: Generations), winner of the tournament’s first round, and Uryens (Keith Buckley, of Virgin Witch and Dr. Phibes Rises Again), who was favored by most observers to win the second. Leondegrance figures that if God wants a fifteen-year-old squire to be king, then fuck it— let a fifteen-year-old squire be king. Uryens, on the other hand, is a stickler for protocol. Arthur jumped the turnstile, so to speak; successful or not, his attempt to draw Excalibur was premature and illegitimate, so his kingship would be equally so. When Leondegrance, Hector, and Kay stand up for Arthur, Uryens declares war on them. (Notice that he does not declare war on Arthur, who as a mere squire lacks the standing to receive a declaration of war. Once again, proper protocol is everything to this guy.) After a period of panic that Merlin helps him work through, Arthur establishes his royal bona fides by coming to Leondegrance’s rescue— and crucially, he wins the day not merely through the deftness of his leadership or the strength of his sword arm, but also by ingeniously exploitating his enemy’s legalistic turn of mind. In the end, it’s Uryens himself who proclaims Arthur king. The aftermath of the battle proves nearly as momentous for the victor, too, for while resting up at Leondegrance’s castle to recover from injuries sustained in the fighting, the boy king meets and falls in love with his host’s daughter, Guinevere (Cherie Lunghi, from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein).

Another jump forward in time shows the adult Arthur consolidating his early triumphs, scouring his realm for knights of great valor and rectitude to become his trusted lieutenants and administrators. In particular, it shows the king’s first meeting with Lancelot of the Lake (Nicholas Clay, from Lady Chatterley’s Lover and These Are the Damned), a wandering Frenchman on a peculiar quest for the one man who can kick his ass in a fair fight. The encounter begins with Arthur and his retinue attempting to cross a bridge which Lancelot has blocked expressly because doing so will lead him into conflict with every passing knight. After watching the stranger pummel Leondegrance and who knows how many of his other followers, Arthur takes matters into his own hands. The first joust is a draw. The second goes to Lancelot, but not so decisively as to make Arthur back down. Hand to hand on foot, Lancelot still has things all his way until, in a rage of wounded pride, Arthur calls up the power of Excalibur, and strikes his opponent a blow that cleaves through parrying weapon and armor alike. But instead of killing Lancelot, the Sword of Kings revolts against the unjust use to which it was put, and snaps clean in two against its target’s unprotected chest. As Lancelot lies stunned, Arthur repents of his rash cruelty, and casts away the broken blade, symbolically renouncing with that gesture the kingship he has so misused. At that, the Lady of the Lake appears, and returns Excalibur to him miraculously whole again; by recognizing and confessing his unfitness to reign, Arthur has paradoxically proven himself worthy of his destiny after all. Meanwhile, Lancelot recovers, and joyously pledges himself to Arthur as his champion, for at last he has found what he was looking for.

In a significant way, the foregoing sequence is Excalibur’s mission statement. With their depiction of the duel by the bridge, its outcome, and the motivations behind it, Boorman and Pallenberg are telling us what chivalry means in this mythic version of the Middle Ages. The story they want to tell requires a perspective internal to Medieval culture, so they propose not only to take all the era’s bullshit about knightly honor and courtly love seriously for the purposes of this film, but even to take feudalism seriously as a potentially non-horrifying form of social organization. Furthermore, they invest the concepts of honor, chivalry, and government by mutual oath with mystical significance above and beyond their status as a code of conduct for warriors and rulers. By showing that the divine or semi-divine spirits of the natural world (the Lady of the Lake, for example) subscribe to chivalric norms right along with the human characters, the filmmakers foreshadow and justify the systemic breakdown that comes later when Arthur, Lancelot, and Guinevere irreparably violate those norms. With all that going on, it’s no wonder that Boorman and Pallenberg let the Lancelot encounter stand in for Arthur’s whole recruitment drive, then rush on ahead to and through the founding of Camelot, the establishment of the Round Table, and the marriage of Arthur to Guinevere.

We need to take those next scenes a little slower, though, because the whole rest of the plot will be driven by three fateful meetings that occur during them. In this version of the story, the Knights of the Round Table are not permanently based at Camelot. True to actual feudal practice, they spend most of their time dispersed about the realm at their own estates, where they act as the king’s representatives. Every so often, though, they gather at Arthur’s castle for what amounts to a convention that puts equal emphasis on shop-talk and relaxation. Lancelot is on his way to one such gathering when he meets a half-feral youth called Percival (Paul Geoffrey), who dreams of becoming a knight. Percival accompanies Lancelot to Camelot, where he takes up a position as his squire. Years from now, that kid’s going to be arguably as great a knight as Lancelot himself. Arthur’s foreign champion is also a player in the second big crossing of paths, because it is his duty and privilege to escort Guinevere from Leondegrance’s castle for the wedding. Lancelot thoroughly charms Guinevere and her ladies in waiting on the trip, and Guinevere more than thoroughly charms Lancelot. Indeed, on his end, it’s love at first sight. He admits as much, too, when the girls of the queen-to-be’s entourage start asking impudent questions about his love life, but not to worry— pillar of rectitude and all that, right? Meanwhile, perhaps most dangerously, the royal wedding brings all of Arthur’s relatives to Camelot, including his half-sister Morgana (Helen Mirren, of Caligula and 2010), daughter of Igrayne and the Duke of Cornwall. Morgana has been a busy girl since we glimpsed her looking on as Merlin confiscated Arthur from his natural parents. She’s been studying witchcraft with great diligence, and she seeks out Merlin at the wedding ceremony in the hope of being taken on as his apprentice. Specifically, she wishes to learn from him the most powerful magic of all, the Charm of Making, which grants the user access to the omnipotent Dragon, greatest of chthonic spirits. Morgana is not to be trusted, however. The traumas of her youth— father murdered, baby brother stolen, mother come to an unspecified bad end— have given her a stronger than usual appreciation for the usefulness of power, and little personal fondness for either Merlin or people related to Uther Pendragon.

Morgana stirs up an impressive amount of trouble in the years to come. Noting the obvious affection between Lancelot and Guinevere, and making the somewhat less obvious connection between it and the knight’s increasingly frequent absence from the Round Table, Morgana persuades Sir Gawain (Liam Neeson, from Battleship and The Haunting) that the queen and her husband’s champion are having an affair. It isn’t true, but when Gawain makes the accusation publicly, Arthur is unable to play his expected role as husband by defending Guinevere’s honor in a trial by combat. A king, after all, must not take sides among his subjects. Instead, the task falls to Lancelot, with the result that the queen really does start seeing him on the side. When Arthur discovers what Guinevere is up to, he falls into such a funk that he abandons Excalibur, and shrivels up into a weak, distant, in-name-only sort of ruler, allowing the kingdom to fall into lawlessness, famine, and disease. (And this is one time when I won’t get pissy with anyone for harping on the phallic symbolism of a sword!) While that’s going on, Morgana bamboozles Merlin into teaching her the Charm of Making, which she immediately uses to imprison him in the Dragon’s netherworld. Then she gets vicarious revenge for her parents, presenting herself to a delirious Arthur in the guise of Guinevere, and getting herself knocked up with the king’s incest baby. As his domain falls to pieces, Arthur conceives in one of his rare moments of clarity the notion of a redemptive quest to undo everything that has gone wrong since the day Morgana first started talking shit about Guinevere and Lancelot. The Knights of the Round Table (now including Percival, who has stepped up into the royal champion spot vacated by his disgraced former master) will fan out across the land to find and recover the Holy Grail. Inevitably, Morgana has a somewhat different vision of the kingdom’s future. She traps and kills the quest knights one by one, keeping Arthur safely enfeebled while their son, Mordred (Robert Addie), grows to manhood. And when the time is right, Mordred will ride out with an army of the fed-up and disaffected to take Camelot by force. Unless, of course, somebody should happen to find that Grail thing in spite of it all…

Excalibur is a real oddity, a movie that fails miserably by most of the normal standards of cinematic storytelling, yet succeeds, sometimes brilliantly, at what it specifically sets out to do. What’s more, its successes on the one scale are often the direct result of its failures on the other. It all comes back to what I called the mythographic sensibility. Myths (and their goody-two-shoes little brothers, fables) differ from other kinds of stories in that the surface-level narrative is rarely if ever the point. The myth of Apollo’s fight with Python, for example, is only trivially about a god killing a dragon. Its true purpose is to explain why Delphi is a holy place, and why you should listen to the benzene-huffing crazy lady in the basement of the temple there. It may also encode a symbolic account of the Doric Invasion, in which the forebears of the Classical Greeks overran, displaced, and ultimately assimilated the serpent-venerating Mycenaeans. Similarly, Excalibur presents the story of Camelot as if it were only trivially about a man chosen by mystical forces to unite Britain, only to lose his kingdom to internal discord sown by a vengeful witch. For Boorman and Pallenberg, the Arthurian legends are about how a knight must be more than just a warrior, a king more than just a dictator, and they encode symbolically the passing away of Celtic paganism before the rising tide of Christianization.

On the face of it, there’s nothing very unusual about that. The importance of correct knighthood and kingship was a vital subtext to the Arthurian legends not only in Thomas Malory’s day, but even in that of Chretien de Troyes and perhaps earlier, and the entire genre of Medieval romance is a veritable Burgess Shale of fossilized pagan influences. What’s weird about Excalibur is that it elevates those themes far above the level of subtext. Merlin warns Morgana against getting into the magic business, telling her that the time for wizards and witches is over, that “the One God comes to drive out the Many Gods.” Meanwhile, it is explicitly the failure of Arthur, Lancelot, and Guinevere to live up to chivalric ideals that plunges their world into such misery that only the Holy Grail can fix it. Because Guinevere cannot accept that Arthur must be king before husband when Gawain accuses her of adultery, she rejects him and bestows her love instead upon the man who would champion her in the trial at arms. Because Lancelot, already in love with Guinevere, cannot resist temptation of that magnitude, he violates his most sacred vow. And when Arthur, unable to bear the double betrayal, shirks his royal responsibilities, even the natural world suffers from his disengagement, because the king and the land are one. As in a genuine myth, this stuff is sitting out on the surface, tangled up with all the simple “who does what, when, where, and why,” instead of skulking in the shadows to be teased out by attentive viewers and/or their English teachers. Movies don’t normally work like that, and in order to make this one do so, it was necessary for the filmmakers to disregard some very basic expectations about how movies do normally work.

To begin with, characterization in Excalibur is sketchy nearly to the point of absence, and very little effort went into grounding the events of the story in the natures and personalities of the people inhabiting it. The principal characters seem to act less out of individual desires and motives than because these things are what they’re fated to do. Even more curiously, the most relatable, understandable figures in the whole film are Merlin and Morgana, the ones who are only semi-human in the first place! I suppose it makes sense that Merlin would come through extra-clearly, though, since it was originally his story that Boorman set out to tell. In one of Excalibur’s rare touches of humanism, it’s possible to interpret the “end of paganism” theme as a conscious decision on the wizard’s part, as the result of his recognition that no good has come of supernatural beings sticking their noses into mortal affairs. (Note that such a reading would imply that Christianity is a human construct, despite Merlin’s line about the coming One God. I don’t think that’s an accident.)

Pacing and structure are another front on which Excalibur looks less like a movie than like something handed down from the pre-modern past through centuries of bardic tradition. I lost track of how many times the movie skips a decade or more ahead in a single change of camera angle, vaulting over a fairly significant turn of events in the process. Characters appear and disappear at the whim of plot necessity, thumbing their noses at modern conventions about creating the illusion of a consistent fictional environment. Gawain, for example, is never heard from until the first time we see Morgana whispering in his ear, and Leondegrance is never seen again after losing his joust by the bridge with Lancelot. Uryens and Kay vanish as soon as Arthur claims his throne, only to pop up again in the final half-hour. And when Arthur comes to visit Guinevere in her convent on the eve of the final battle against Mordred, it’s the first we’ve heard that she became a nun in penance for her infidelity.

Again, though, there’s a conscious purpose behind all these departures from the rules of narrative filmmaking. Boorman and Pallenberg don’t want Excalibur to look or feel like anything normal or modern. They want it to seem antique and alien, just as its source material seems when read today. The same theory underpins the anachronistic production design, the vagueness of the claimed temporal setting, and so forth. It’s why people who supposedly lived in the 6th century are tromping around in a 12th-century countryside while dressed, armed, and armored in the manner of the 15th century. If you take Excalibur as a movie about King Arthur, it’s likely to disappoint you, because that’s not what it’s supposed to be. Rather, it’s an attempt to put the legend of King Arthur onto film, and in that capacity, it’s very impressive indeed.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact