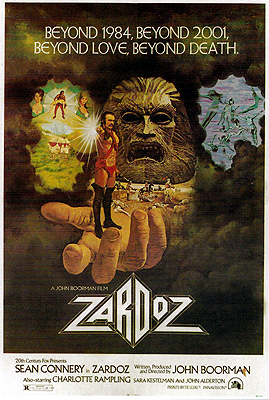

Zardoz (1974) -***½

Zardoz (1974) -***½

Except in the case of Asian monster movies (and often enough even there), a one-word title that isn’t really a word is something close to a guarantee of utter awfulness. Furthermore, the specific form of that awfulness is generally pretty predictable. Faced with such a title, it’s usually safe to expect a cheap-shit sci-fi action flick, probably featuring a former wrestler or a washed-up TV personality. Also, there’s a better than even chance that the movie will have been released directly to video. Zardoz does not fit that paradigm, however. This is not to say that Zardoz isn’t awful, for indeed it is terrible in ways that frequently defy description. No, what makes it exceptional among sci-fi films with blatantly made-up one-word titles is that it didn’t come by its wretchedness through the activities of some fool with no money and less ability, who got it into his head one day to try passing Jesse “the Body” Ventura off as an android bounty hunter from the future, or some such thing. Rather, Zardoz is what happens when a highly intelligent and extremely talented auteur director is given all the money he can spend, all the drugs he can ingest, and completely untrammeled freedom to make whatever the hell movie he feels like. One does not produce so breathtaking a fiasco by pinching pennies and thinking small.

The first thing we see is a disembodied head that introduces itself as Arthur Frayn, False God (Alien3’s Niall Buggy), known to his worshipers as Zardoz. Frayn has a handlebar moustache drawn onto his face with black magic marker, and is wearing, shall we say, a most unfortunate headdress; the last time I saw anything truly comparable was when the “rabbit” stopped by the library in Alice in Wonderland. After floating about in the void for a bit, Frayn mentions that he doesn’t really exist, being but a figment of John Boorman’s imagination, and suggests that we might all be figments of somebody’s imagination, too. If you happen to have any peyote on you, this might be a good time to eat it— the movie will probably make more sense that way.

Anyway, next comes something arguably even sillier: another floating head (this one 40 feet tall and made of stone), and riding out to meet it at the head of a column of horsemen, Sean Connery in a red leather diaper, black vinyl fuck-me boots, and a fetching pair of bandoliers crossed over an otherwise bare chest that looks to have drooped just a little since the days of the 1953 Mr. Universe competition. Hovering in the air above Connery and his cavalry, the giant head begins noisily pontificating about how the gun is good and the penis is evil, and then vomits about a thousand rifles and a corresponding quantity of ammunition from its perpetually grimacing maw. This, as you might have guessed, is Zardoz. Once its fusillatory largesse has been collected, Zardoz sets itself down to receive a counter-offering from its worshippers, in the form of some two tons of grain, which the horsemen shovel into its mouth before it flies off again whence it came.

The thing is, James Bondage has stowed away amid all that cereal, for some purpose as yet known only to himself. He seems to be taken somewhat aback to discover that the interior of his god is thoroughly stocked with inanimate naked people in clear plastic bags, but his response is plenty decisive enough when Arthur Frayn stupidly emerges from Zardoz’s cockpit. Evidently taking the god completely at its word, he shoots Frayn in the back, and kicks him out through the open mouth. Zardoz must have an automatic pilot system, though, because the huge stone head nevertheless comes to a safe and more or less comfortable landing once it reaches its destination. The place is a tranquil-looking English village, which initially seems to be deserted. Our deicidal maniac of a hero blunders from house to house for a bit, marveling over (and occasionally becoming enraged by) the various super-high-tech doodads he finds in each, but then the villagers return from wherever it is they’ve been, and he falls into their hands.

And, oh— Zardoz be praised! At last we get some fucking exposition around here! Turns out James Bondage has both a name and a clearly defined role in the great scheme of things. He’s called Zed, and he’s an Exterminator. It takes a good long while for all the details to come out, but the short version is that the year is 2293, and the world is completely screwed. Most of the human population— the Brutals, as they’re known— have reverted to a level just slightly above the animal (which doesn’t stop them from dressing in conservative 20th-century business suits, but never you mind that). The Exterminators, meanwhile, are the chosen people of Zardoz, whose covenant with them puts me in mind of one of R. Lee Ermey’s lines from Full Metal Jacket: “God has a hard-on for Marines, because we kill everything we see.” As for the village and its rather effete inhabitants, it is called the Vortex, while they are the aptly named Eternals. The Eternals do not age; they do not die; and because the Tabernacle— the computer that keeps everything in the Vortex running smoothly— apparently keeps a stock of replacement bodies always on hand (this presumably explains the shrink-wrapped nudes inside Zardoz’s cranium), they can’t even be killed. There’s a downside to all that, however. The resources of the Vortex are finite, so if nobody is dying, that means nobody can be born, either, and the only way to be absolutely certain of that is to eliminate the sex drive completely. Also, because the Eternals are all stuck with each other forever, there is an enormous premium on consensus within the Vortex— and since they’re all telepathic, too, tact alone isn’t going to get the job done. Dissent and negativity of any kind have therefore been outlawed, violations being punishable by induced aging. So: no sex, no secrets, no disagreement, no contact with the outside world… Is it any wonder the Eternals are all bored out of their undying skulls?

Unsurprisingly, the temporarily late Arthur Frayn was one of the Eternals, but it would seem that none of the Vortex’s other inhabitants had any idea what he was up to out there in the world, beyond that he and his flying stone head did invaluable work supplementing the Eternals’ food supply. It’s news to them that he was impersonating a god, and his aims in organizing the Exterminators are a total mystery. (If you’re wondering how he kept that under his very silly hat when secrecy among Eternals is supposed to be impossible, well… so am I.) Zed might know a few of the answers, but since he doesn’t seem to understand any of the questions, getting them out of him is going to be rather a tall order. May (Sara Kestelman, from Lisztomania— a movie that might be even weirder than Zardoz) wants to subject him to comprehensive study, utilizing every available means. Consuela (Charlotte Rampling, of Orca and Asylum) contends that the Eternals would be better off just killing Zed and forgetting about whatever screwy shit Frayn’s been doing. The decisive influence comes from Friend (John Alderton), who cannily points out that here, at last, is something interesting.

Zed quickly becomes practically everybody’s hobby. Consuela frets over his potential as a disruptive influence. Avalow (Sally Anne Newton) keeps offering him weird mystical pronouncements and waving her tits at him. May falls in love with him over the course of her studies (a development which might, just maybe, have something to do with his demonstration of the lost art of the erection). And perhaps most importantly, Friend takes to showing him all around the Vortex, and explaining the way life there works. It is from Friend that Zed learns (as do we) about the Tabernacle, about the Vortex’s odd legal system, and most importantly, about the two greatest internal threats to the Eternals’ supposed utopia. As I said, the Eternals are bored, but boredom among these godlike beings is a rather more serious business than it is for mere mortals. The most grievously understimulated are in danger of becoming apathetics, losing interest in life so completely that they cease to be capable of doing anything at all— an apathetic won’t so much as change facial expressions even in response to a direct physical attack! As for the other serpent in the garden, it’s to be found in what amounts to the Vortex’s penal colony. Remember, age is the penalty for rule-breaking. The most incorrigible renegades get advanced all the way into what, for a normal human, would be their final decrepitude, forced to live out the rest of eternity in feebleness and senility. Perhaps not coincidentally, the arch-renegade of the bunch is the once-brilliant scientist (Christopher Casson) whose idea the Vortex was in the first place, and everybody is just a little bit worried that maybe there’s more going on behind that blank stare of his than meets the eye.

Those, as I said, are the big internal threats. What nobody in the Vortex understands— and what even Zed perceives only dimly— is that Arthur Frayn’s life’s work has been to create an external threat powerful enough to destroy the whole system at a stroke. The Exterminators all know that they are the Chosen of Zardoz, and that they have been enlisted to kill and destroy on his behalf. Well Zed, we shall gradually discern, is Chosen among the Chosen, the end-product of generations of selective breeding meant to perfect him both physically and neurologically, giving him an edge over the Eternals, who arrived at their “perfection” through artificial, technological means. In him, Frayn has created a way to end at last the eternal lives which he and his fellows have come to find so burdensome, and now that personification of the immortals’ repressed death-wish is roaming free all over the Vortex. Furthermore, Zed has managed to keep one thing secret from his hosts— he hid himself away in all that grain because he had discovered Zardoz’s falsity, and hoped to avenge himself upon the being who had deceived him his whole life long.

The astounding, frustrating, and wonderful thing about Zardoz, depending upon your mood, is that it really does come close to being a legitimately great film— specifically, I’d say it comes within about two tabs of greatness. The idea of a utopian society that has perfected its way to utter misery had been used before, of course. Indeed, the crew of the USS Enterprise seemed to come into contact with such a civilization once or twice a month during the two and a half televised years of their five-year mission. There’s a reason the premise is so durable, though, and a writer/director of John Boorman’s abilities ought to have had no trouble crafting a variation on it that would at least equal a Gene Roddenberry TV production. Sure enough— at the conceptual level— Zardoz is an exceptional astute meditation on the perils of utopia. It takes as its starting point a utopian vision so extreme that only religious thinkers have the nerve to put it forward with a straight face (although it is, in a sense, the unacknowledged asymptote toward which medical science and public health initiatives have been nudging the human condition ever since the germ theory of disease was developed in the mid-19th century), and then meticulously examines the likely practical side-effects of life without death or infirmity. The conclusion Boorman reaches— and I don’t think it takes an atheist to recognize the validity of the reasoning behind it— is that heaven is really going to suck so long as humans remain recognizably human. But despite that pessimistic message and the centrality of a sham religion to the proceedings, Zardoz is nothing so simplistic as an allegorical polemic against faith or spirituality. It is strongly implied that the Eternals have failed to transcend their human limitations precisely because they tried to cheat their way to godhood technologically. Zed, the truly transcendent post-human, had to be created the old-fashioned way, via centuries of evolution— and that evolution was guided by a higher power, in accordance with a conscious agenda. In short, what Boorman has done in Zardoz goes well beyond the conventional bounds of science fiction. He has created a mythology in which a small, self-appointed elite of humanity, driven by desperation and hubris in roughly equal measure, raise themselves to the threshold of divinity, but are unable, in the end, to cross it under their own power. As these failed gods come to regret their folly, a messiah emerges from among them, offering two distinct kinds of salvation: the merciful release of death for his own kind, and a chance to achieve what his people could not for the debased masses who were left behind by the Eternals’ botched experiment in apotheosis. And though that messiah cloaks his project in hocus-pocus and duplicity, the spiritual goods he’s dealing are indeed the real thing. This is immensely powerful stuff here, and it would take a filmmaker of rare vision even to attempt working with it.

But then there are those two extra hits from the blotter, and what a difference a few hundred micrograms makes! Though its sights were set higher than those of virtually any other sci-fi movie of its decade, Zardoz came out a pompous, self-indulgent, incoherent mess of the sort you can get only by pouring hallucinogens all over an exceptionally acute mind. Sometimes the movie goes wrong at the level of imagery. For instance, take the penal colony for the renegades. In the abstract, the idea of having to spend eternity crapping on yourself and forgetting your own name is more horrifying than practically anything else I can think of, but when we get to see this nursing home of the damned for ourselves, it turns out to involve, well, a whole lot of very lethargic ballroom dancing. In fancy evening dress. Yeah. Similarly, the highly eccentric production design gets in the way an awful lot. It’s undeniably memorable and distinctive, and may even be unique in some aspects, but I’m thinking there’s probably a very good reason why nobody else ever dressed up Sean Connery as an S&M barbarian, or had a giant, flying stone head puke rifles all over the English countryside. Other times the imagery itself is quite clever, but Boorman just doesn’t know when to lay off it. Late in the film, there’s a scene in which the Eternals, having gotten wise at last to Zed’s true business in the Vortex, become very excited about the prospect of having their society destroyed, and decide they’d like to do one last collective good deed for the species before getting in line to embrace death. Because Zed’s selectively bred mental capacity is such that he literally never forgets anything, the Eternals decide to impart to him everything they’ve learned over the centuries through a form of tactile telepathy. In practice, this means Zed having sex with each of the Eternal women in turn (Vortex society’s mildly matriarchal character is just one more of the potentially interesting ideas in Zardoz that never get developed into anything worthwhile) while vast torrents of text are projected onto the participants, scrolling from the women’s bodies down onto Zed’s. It sounds kind of dumb when I describe it, but when you think about it for just a moment, it’s a pretty efficient and imaginative means of showing the audience a process that doesn’t remotely lend itself to visual presentation. The thing about visual shorthand, though, is that it really does need to be short. Instead, the data-dump gang-bang goes on and on and on, quickly transforming from a sly solution to a seemingly insoluble problem into just another ridiculous 70’s art-movie sex scene. And of course, a fair amount of what goes on in Zardoz really is nothing but a bunch of hippy bullshit— with Arthur Frayn’s pseudo-intellectual opening address to the audience serving to start the movie off on exactly that ill-considered note. Taken together, it makes Zardoz one of the foremost examples of the power of sheer indiscipline to ruin— often in staggering and hilarious ways— what should by rights have been a fine film.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact