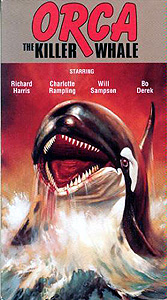

Orca/Orca: The Killer Whale! (1977) -***½

Orca/Orca: The Killer Whale! (1977) -***½

I’m fairly confident that just about all of my regular readers will have encountered some version (I’ve seen it rendered in several slightly variant phrasings) of the notorious Dino De Laurentiis quote: “When my Kong die, everybody cry. Nobody cry when Jaws die.” Whatever its aptness in the context of the picture it was intended to boost, that line may just be the key to understanding Orca, the last entry in the loose trilogy of monster movies produced by De Laurentiis from 1976 to 1977. Certainly it’s my touchstone for this very peculiar film. When I look closely at Orca, the first thing I see is De Laurentiis taking his earlier boast to the press as a challenge to himself: maybe he could make people cry over Jaws after all. “Jaws” would have to be recast as something other than a shark, of course, in order to get around that “lifeless eyes, like a doll’s eyes” problem, but perhaps it wasn’t necessary to go all the way to a giant ape. Mightn’t a killer whale be just cuddly enough to evoke a broad base of audience sympathy, while still retaining some of the great white shark’s alien implacability? A pelagic apex predator, much bigger than any living species of shark fierce enough to do serious harm to a human, and a great deal smarter than even the cleverest fish, an orca would unquestionably be a deadly threat if provoked to violence, yet Shamu (or at any rate, Shamutm) was still dependably packing in the crowds at Sea World with her carefully choreographed antics, and bumper stickers were exhorting drivers to “Save the whales!” all across the English-speaking world in 1977. Dino’s choice of species for his sympathetic monster brings me in turn to the second thing I see when I look closely at Orca. More than just a cetacean version of Jaws, this movie is also Moby Dick if Captain Ahab were the whale!

Somewhere off the little Newfoundland fishing village of South Harbor, marine biologist Rachel Bedford (Charlotte Rampling, from Angel Heart and Zardoz) is recording whale song with the help of a grad student named Ken (Robert Carradine, of The Pom Pom Girls and The Tommyknockers). Suddenly, two equal and opposite hazards loom up to threaten the researchers. Down below the waves, a 20-plus-foot great white shark cruises in to investigate the racket attendant upon Bedford’s dive to retrieve the underwater microphone (well, it’s a racket if you have shark ears), forcing her to seek shelter amid a cluster of boulders on the seafloor. Meanwhile, up on the surface, a boatload of shark-hunting yahoos come barreling over in pursuit of the enormous fish, wantonly disregarding the little pontoon skiff in which Ken is waiting to collect Rachel whenever she emerges with the mic. The leader of the yahoos is an Irishman by the name of Nolan (Richard Harris, from The Hunchback and Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone); his crew consists of the grizzled and elderly Novak (Keenan Wynn, of Wavelength and The Devil’s Rain), the young and impetuous Paul (Peter Hooten, from The Student Body and 2020 Texas Gladiators), and Paul’s girlfriend, Annie— who, being played by Bo Derek (seen later in Bolero and Tarzan the Ape Man), has no discernable personality traits whatsoever. This is no trophy-fishing expedition for Nolan and his companions. The skipper knows that no aquarium in the world has a captive great white in its menagerie, and he’s gotten it into his head somehow that this one will fetch him $10,000 per foot if he can take it alive. He thus naturally resents the disruption to the chase posed by Rachel and Ken, and he tells them as much after the shark breaks off its vigil around Bedford’s hiding place to check out the engine sounds of Nolan’s boat instead, giving her a chance to escape topside. Nevertheless, Nolan somewhat grudgingly offers to take the researchers aboard, since a tiny dinghy is clearly poor protection against an increasingly agitated great white. Only Rachel makes it onto the Bumpo’s deck, however; Ken is tossed out of the skiff by a sudden swell, and the shark makes a beeline for him.

Now this is a moment that the true connoisseur of late-70’s critter flicks will greet with a knowing smile, but which may require some elucidation for the benefit of laymen. Such was the impact of Jaws that Carcharadon carcharias became a sort of gold standard for monsters during the second half of the decade, and one of the favorite tricks of the era’s creature features was to establish their monsters’ credentials by depicting them fighting and killing a great white. You’ll recall that even Zombie felt compelled to play the “badder than a shark” card before the protagonists’ arrival on Matul. Anyway, it now comes to light that those whales Bedford was recording were killer whales, and one of the big bulls splits off from the pod to score one for Team Mammal by rescuing Ken. In its way, the aquatic duel is even more ridiculous than the gorilla-vs.-shark sequence in A*P*E. Nolan and his crew are rendered justly speechless by the spectacle. (Incidentally, the makers of Jaws 2 would pay Orca a strange sort of compliment the next year, using a fight against a killer whale as their bid to restore the great white shark’s position as the scariest thing in the sea.)

In the coming weeks, Nolan begins doing a most uncharacteristic thing— he starts hanging around the local college to listen in on Bedford’s lectures about orcas. Partly this is because he hopes to lure Rachel into bed with him, but it’s also because he has concluded that if an orca can beat up a great white, then surely an aquarium would pay more for the whale than they would for the fish. It’s an open question, frankly, which project is more obviously unrealistic. There’s no doubt about which one goes more calamitously awry, however. Heedless of Bedford’s increasingly strident arguments for both the impracticality and the immorality of capturing an adult orca, and making a mockery of his own assurances that to maim or kill a whale by accident in the attempt would not be his style, Nolan takes the Bumpo out to sea with visions of riches and glory dancing before his eyes, but bungles the hunt in pretty much every way within his power. Missing the bull which he selected as his quarry with his first shot would have been but an annoyance, but nicking his fin and hurting him just enough to piss him off is a much more serious matter. And that’s nothing compared to hitting the bull’s mate by mistake, which is furthermore nothing beside misjudging the dosage in the tranquilizer harpoon. The harpooned female is left just dopey enough to blunder into the Bumpo’s propeller, dealing herself grievous injuries that are mysteriously nowhere to be seen a moment later, when Novak gets a line around her flukes, and hoists her out of the water. (The whale’s wounds will come and go at random throughout the remainder of the first act, but at no point are they ever slightly commensurate with the means whereby they were inflicted.) The capper to the whole sorry fiasco occurs only then, for the female is several months pregnant, and the cascade of traumas causes her to miscarry revoltingly, straight onto the Bumpo’s quarterdeck. None of this goes unnoticed by the bull, in case you were wondering.

In point of fact, the male orca spends the whole rest of the day following the Bumpo back toward South Harbor while Nolan and his crew attempt to figure out what in the hell they’re going to do with a dying killer whale. They’ll never need an answer to that question, though, for the male has no intention of leaving his mate in Nolan’s hands. He attacks the Bumpo after dark, and with the boat’s stability already compromised by the several tons of deceased orca hanging in its upperworks, there’s a real danger of capsizing due to the sustained underwater battering. Nolan orders Novak to cut the female loose, but dumping her overboard will require swinging the crane out past the gunwales and climbing out to the end of the overhanging boom to sever the rope. When the bull sees Novak thus exposed, he launches himself from the water and seizes the luckless old sailor. So not only has Nolan failed to get rich quick by capturing a live orca, and gruesomely slaughtered a pregnant whale by mistake, but he’s now gotten his oldest and best friend killed.

That whale isn’t finished with Nolan yet, either— not by a long shot. He continues following the Bumpo’s wake as far as the cove where Nolan anchors for the night, pushing his mate’s carcass all the while. Unnoticed by the sleeping humans aboard the boat, the male deposits the female on the beach for Nolan to find the next morning. All that’s missing is a note reading, “This is a message from Don Corleorca.” Still, Nolan is either a very dense man, or one completely unaware that his entire universe exists at the behest of two Italian screenwriters, for it takes Rachel Bedford (who is wise in the ways of things she has no possible means of knowing) to spell out for him that the dead female was beached by her mate as a direct challenge to the skipper. Nor is Bedford alone in that interpretation. No sooner has she told Nolan that the whale is calling him out than Jacob Umilak (Will Sampson, from Poltergeist II: The Other Side and The White Buffalo), an Indian who teaches “at the Tribal School up north,” arrives on the scene to back her up: “She knows it from the university; I know it from my ancestors.” And for that matter, even Swain (Scott Walker, also in The White Buffalo), the head of the local fishermen’s union, eventually agrees that Nolan obviously has a showdown with the other orca in his future— and the sooner the better. If the whale hangs out around South Harbor for any length of time, he’ll scare away all the fish, and that’ll be it for the local economy this season. Nolan, however, surprisingly wants no part of this interspecies vendetta. You see, he relates to the whale, on account of the drunk driver who killed his pregnant wife by foolhardy accident not long after the two of them came to America. (Yes, I know. Newfoundland is in Canada. Don’t tell me— tell Luciano Vincenzoni and Sergio Donati.) The only interaction Nolan wishes to have with the bull orca now is to apologize to him.

The whale isn’t interested in apologies, though, and he launches an unmistakable campaign of terrorism against South Harbor, calculated to make the skipper’s neighbors force him to come out and fight. First he wrecks the other fishermen’s boats. Then he fulfills Swain’s prediction about chasing away the fish. Then he pulls off an utterly amazing trick with a gas pump, a kerosene lantern, and the petroleum refinery on the cliff overlooking the town that gets South Harbor burning like Tokyo after one of Curtis LeMay’s thousand-bomber raids. But what finally changes Nolan’s mind is an attack on the house where he lives with Paul and Annie, which conveniently stands on a set of pilings directly over the harbor. The orca knocks the house half-into the water by taking out its supports, and bites Annie’s leg off when she falls within his reach. The next day, Nolan and Paul are back aboard the Bumpo for another whale-hunt, with Umilak, Rachel, and Ken rather incongruously filling out the crew.

Mind you, just about everything that happens in Orca is rather (at the very least) incongruous. Honestly, the only character in the film whose behavior makes any kind of sense in aggregate is the fucking whale— and we have to give even him credit for both a whale-song-to-English interpreter and a network of spies and collaborators ashore before his behavior begins to make actual sense. I mean, sure, whales are smart, and killer whales in particular display problem-solving abilities that put plenty of primates to shame, but for this whale to do what he does, it’s necessary for someone to have told him Nolan’s home address! It’s necessary for him to have learned enough about human society to be familiar with concepts like social shaming and peer pressure. It’s necessary for someone to have explained to him about fire (which he would obviously never have seen out in the open ocean) and gasoline— and for someone to have switched out all the fuel in the dockside pumping station in preparation for the big kerosene lantern attack, since maritime internal combustion engines typically run on diesel, and diesel fuel doesn’t behave that way. And that’s to say nothing of the myriad ways in which Vincenzoni and Donati have misunderstood and/or misrepresented the killer whale’s natural lifestyle, which bears very little resemblance to what’s portrayed in the film. Most notably, the lifelong bond around which orca society is structured is that between mother and offspring, not that between mated male and female. Indeed, killer whale bulls only rarely take mates from within their own pods; rather, they generally hook up with females from neighboring pods, then go running home to Mom once the deed is done. But bogus or not, at least the orca has a clear motivation, and even his most blatantly impossible actions are plainly consistent with it. The humans, on the other hand? Hoo-boy…

Nolan’s inconsistencies are probably deliberate, insofar as we’re encouraged to regard him as not terribly bright and totally out of his depth, and to that extent if no other, Orca is completely convincing. This, after all, is a guy who makes his entrance by attempting to capture a great white shark alive on a boat that has no apparent facilities for maintaining a large and demanding fish even if he did somehow manage to land one without killing it in the process. Nolan is subjected to a lot of conflicting pressures over the course of the film, and it makes some sense that he would drift from one influence to the next without purpose, plan, or program. Nevertheless, the filmmakers did themselves no favors by withholding the story of the drunk driver until roughly the halfway point. That incident is the crucial factor governing Nolan’s relationship with the grief-maddened whale, and until it comes to light, it seems absurd that a professional fisherman would have a single qualm about killing anything that lives in the sea.

The people pushing Nolan this way and that, by contrast, have no such excuses for their incoherent characterizations. Let’s start with Annie, who incorrectly advises Nolan that killer whales are monogamous, and that by catching one, they “might be busting up a happy family”— while standing in the Bumpo’s pilothouse, as the boat closes in on its quarry. Surely the time and place to raise that complaint was hours if not days ago, on dry land, and if Annie is so opposed to even non-lethal whaling, then why the hell isn’t she back in South Harbor, sitting out the mission as a conscientious objector?! Swain’s behavior is similarly garbled. At all times, his sole concerns are the economic health of South Harbor’s watermen, and the possible impact of the orca’s activities thereupon. As such, we would naturally expect him to advocate tirelessly for the whale’s destruction, but that’s not quite what happens. Sure, he spends most of the movie in that mode, and he is the mastermind behind the other fishermen’s efforts to force Nolan to clean up his mess, but in his first appearance, he urges Nolan to give up orca-hunting. “Folks around here are superstitious about those things,” he says, before going on to explain about the negative effects of killer whale residency on fisheries. Much as with Annie’s line about busting up happy cetacean families, it would be one thing if that initial encounter between Swain and Nolan had occurred prior to the hunt; then we could ascribe the change in Swain’s position to a change in the surrounding circumstances. Instead, though, he cautions Nolan against whaling off South Harbor after the orca has dumped his mate’s body on the beach, and after he has been spotted lying in wait for Nolan outside the entrance to the harbor proper. That is to say, Swain switches his prescription for dealing with the orca situation without any outside stimulus. And then there’s Jacob Umilak, whose actions are so nonsensical in sum that they lap themselves to make a different kind of sense from what the screenwriters seem to have intended. Umilak, as one would expect of an Indian in a bad Hollywood movie of this vintage, is basically the Lorax, except that he speaks for the whales instead of the trees— although I’m sure that if this were a movie about a killer tree, he’d be happy to speak for those, too. It is thus puzzling indeed when he straps on his spear and magic helmet, and starts singing “Kill the Orca” right along with Swain and the other watermen, even as he continues to stand up for the whale’s claim to be the justified party in this situation. The funny part, of course, is that that’s exactly what somebody who was in real harmony with nature (as opposed to the 70’s eco-guilt version of harmony) would do. Nature, after all, involves a whole lot of killing, and what could be more natural than trying to kill something that wants to kill you?

The undisputed Queen of Incongruity, though— her position impervious to attack by even the most determined and well-qualified pretender— is Rachel Bedford. Compare, for starters, two of the tiresome speeches that she’s forever making on the slightest provocation, the uniquely ill-organized college lecture that fills in the space between the two first-act fishing expeditions and the pompously gloomy voiceover that accompanies the outset of the Bumpo’s climactic voyage. During the former, Bedford makes in passing the utterly absurd assertion that among the unexpected points of similarity between humans and killer whales is the latter’s “profound instinct for vengeance.” But then, some fifty minutes later, she muses, “I told myself that I was somehow responsible for Nolan’s state of mind, that I had filled his head with romantic notions about a whale capable not only of profound grief— which I believed— but also of calculated and vindictive actions, which I found hard to believe, despite all that had happened.” So which is it, lady?! You can’t even realistically argue (as the screenwriters feebly attempt to) that the instinct-for-vengeance bit was part of a deliberate snowjob meant to dissuade Nolan from his orca-hunting mission by playing to his presumed ignorance and superstitious tendencies. For one thing, it hardly seems likely that Bedford would alter the content of her college lectures for Nolan’s “benefit,” writing off her own students as collateral casualties of her whale-saving bullshit campaign. And even if Bedford did take such a flexible reading of her professional ethics, the lecture-hall scene happens (and here we go again) before Rachel learns that the fisherman had decided to trade up from sharks to whales. Similarly, just you try reconciling her early certitude about the vigilante orca’s motives, intentions, and game plan with her protestation shortly before the attack on Nolan’s house that neither she nor Nolan nor anybody else really knows what the whale wants! (It’s a telling bit of irony that one of the very few truly sensible statements made by anyone throughout the entire movie is patently false within the context of this story.) Bedford can’t even make up her damn mind what she thinks of Nolan personally, vacillating without apparent cause between inexplicable attraction and perfectly reasonable detestation and contempt. If this woman has any idea what she’s doing at any moment of the story, there’s certainly no evidence to that effect— even after the filmmakers went back to add intrusive voiceover narration by Charlotte Rampling purporting to grant us insight into Bedford’s thoughts and feelings.

The continuous failures of character logic are only part of what makes Orca such a tremendous joy, however— a big part, to be sure, but merely that. For the rest, I might best sum up by saying that Orca is among the De Laurentiest of all Dino De Lauretiis’s 1970’s productions. One must always remember when considering his career that De Laurentiis was an Italian, and that despite his publicists’ habit of describing him (with some validity during the 1970’s) as the most important independent producer in Hollywood, he continued to embody the values of Italy’s commercial movie industry even after shifting his base of operations. He shared with his contemporaries in the Old Country an unshakable faith in the drawing power of the derivative, the lurid, and the insane, but unlike a Fabrizio de Angelis or an Ovidio Assonitis, he had access to virtually unlimited amounts of money with which to buy counterfeit respectability. We should not be too surprised, then, that he approached his productions with all the crass boorishness of the nouveaux riches, making what amounted to bigger, louder, and more garish versions of the wide-ranging exploitation pieces that might have become his specialty had he stayed at home. So of course Richard Harris and Charlotte Rampling come across here like gone-to-seed Hollywood heavyweights slumming their way through a low-rent spaghetti sleaze-fest for the sake of this month’s boat payment; except for the low-rent part, that’s exactly what they were. Of course Bo Derek got cast as Annie even though she gives every indication of being mortally terrified of the camera; she was a cute blonde with big tits, and where Dino came from, it wouldn’t even have mattered what language she spoke. With the assumption in mind that the formula for success was to do last year’s hit over again, only weirder and sicker, why wouldn’t De Laurentiis cash in on Jaws by making the first (and to the best of my knowledge, still the only) animal-attack flick to side openly with the animal, and why wouldn’t he go out of his way to include something like the unforgettably nauseating miscarriage scene? Why wouldn’t he commission a script that runs with the hints of Moby Dick that can be discerned in Jaws’ third act until they turned into the story of one whale’s quest for vengeance against the human who had wronged it? And since he could spend a fortune while he was at it, giving the finished product the appearance if not the reality of a prestigious event movie, why wouldn’t he do that as well?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact