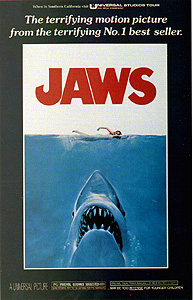

Jaws (1975) ****½

Jaws (1975) ****½

We begin with what is, for better or for worse, one of the most heavily copied opening scenes in cinema history. A bunch of shaggy young people are hanging out on a beach on what we will later learn is Amity Island, somewhere off the Atlantic coast of New York State. While the campfire crackles cheerfully and their friends engross themselves in each other’s company or the various intoxicants being passed around, a boy and a girl get up and leave the party together, headed for the water. The girl strips as she runs, and that’s all her would-be partner needs to convince him to pursue to the best of his alcohol-impaired abilities, but the booze in his system is too much for him; he passes out on the sand before he manages to catch up and join the girl in her pre-dawn skinny dipping. He’s really better off, though, because the camera suddenly switches perspectives to gaze up at the girl from below, slowly closing in on her while a double bass plays a musical cue that just about everyone in the Western world knows by heart on the soundtrack. Cut again to the surface as something takes hold of the swimmer’s leg, jerks a couple of times, and then drags her screaming below the waves. It’s hard to imagine today how the makers of horror movies ever functioned before the invention of the death-by-POV-cam prologue, and thus it’s tempting to believe that it has always been with us. But everything in human life has a beginning, and though the prologue scene in Jaws certainly wasn’t the first of its type, it does seem to have been the one that got the ball rolling. Within five years, it was next to impossible to find a horror flick that didn’t start in more or less this way.

The same principle holds true for a lot of things about this movie. Simply put, Jaws is a tremendously influential film, in ways both obvious and obscure. It’s difficult to miss the huge number of knock-offs that came in its wake, which have ranged from comparatively well thought-out reinterpretations like Grizzly to dim-witted exercises in outright plagiarism like Great White (a movie which was actually sued out of American theaters by Universal’s legal staff). There have been satirical semi-spoofs like Piranha and Alligator, full-on parodies like the swimming scene from Attack of the Killer Tomatoes, and— of course— a string of increasingly embarrassing sequels that took fully twelve years to peter out. Less obviously, bits and pieces of Jaws have shown up in slasher movies (check out The Grim Reaper for an especially eye-popping example), horror-tinged sci-fi films, and old-fashioned straight-up monster flicks, and continue to do so to this day. And perhaps most infamously, Jaws is widely (and I think correctly) given the credit/blame for spawning the Hollywood summer blockbuster as we know it today. I personally don’t look at this facet of its history with the same level of ire as do many critics, for the simple reason that I rather enjoy that sort of movie, or at least I did up until the last brain cell in the summer blockbuster’s head withered up and died sometime around 1990. I happen to like Star Wars, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and their kin from the 70’s and 80’s, and if it’s true that stinkers like the 1998 remake of Godzilla would never have happened had it not been for Jaws, then the same goes for those earlier, compulsively enjoyable spectacles of escapism. I’m sure, however, that there are those who would argue that the loss of Indiana Jones would not have been too high a price to pay in order to be spared The Mummy in 1999. Perhaps they’ve got a point...

But enough about all that; let’s get down to business. The man who will soon have to deal with the ugly situation developing in the waters off Amity is Martin Brody (Roy Scheider, whose star rose very fast indeed after his initial appearance in the mostly forgotten Curse of the Living Corpse), the island’s new chief of police. Brody moved from New York City to Amity with his wife, Ellen (Lorraine Gary), and two sons last autumn, apparently attracted by a combination of Amity’s more relaxed pace and the diminished scale of the town’s problems as compared to the big city— there hasn’t been a homicide there for some 25 years, and Brody will later describe Amity as a place where one man can make a real difference. So it’s a bit ironic, then, that Brody will spend his first summer on the island dealing with a crisis far more menacing, in its way, than anything he would have encountered back home. The disappearance of the skinny dipping girl comes to Brody’s attention the morning after, when his deputy calls him at home to pass on the drunk boy’s missing-person report. Brody heads out to the beach with both witness and deputy, and he doesn’t have to search too long before the upper third of the girl’s mangled body turns up on the beach amid a swarm of hungry crabs. The medical examiner says it looks like a shark attack, and Brody decides to close the beaches.

Amity, however, is a summer town, its economy entirely dependent on the money spent by tourists during June, July, and August for its survival the other nine months of the year. Closing the beaches is thus a very serious business in Amity, and not one that Mayor Larry Vaughn (Murray Hamilton, from The Amityville Horror and The Boston Strangler) and the Board of Selectmen want to undertake lightly. In fact, it isn’t even noon by the time Vaughn has talked the coroner into revising his opinion to take into account the possibility that the dead girl was cut up by a boat propeller. Without the medical examiner’s backing, Brody has nothing to support his position in favor of closing the beaches, and he is forced to back down.

The change of plan doesn’t last long, though, because just days later, ten- or twelve-year-old Alex Kintner is killed by what is unmistakably a shark in broad daylight, in plain view of a beach-full of witnesses. There’s still opposition to closing the beaches— not just from the mayor and the selectmen, but from the townspeople as well— but Brody is able to force a brief closure shortly before the all-important Fourth of July weekend. Meanwhile, the parents of the second victim have put out a $3000 bounty on the killer shark, leading to utter chaos in the waters around Amity, as anyone with access to a boat comes to try their hand at shark fishing. In all the ruckus, the more sober offer of a professional fisherman named Quint (Robert Shaw) to catch the shark for $10,000 goes mostly unheard. Indeed, just about the only responsible thing that anyone on Amity does in the immediate aftermath of the Kintner boy’s death is to call in marine biologist Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss, of Close Encounters of the Third Kind) to assist them in devising workable anti-shark measures. Hooper confirms that the girl from the first scene was killed by an exceptionally large shark, and when one of the more organized groups of freelance bounty-fishermen hauls in a 13-foot tiger shark, the ichthyologist urges caution. True, tiger sharks have been known to attack swimmers, and true, this particular tiger shark could have been the culprit, but Hooper’s measurements of the shark’s bite radius don’t match the wounds on the dead girl he examined earlier. But the people and politicians of Amity are so eager to put their shark nightmares behind them and get on with the summer that no one but Brody takes Hooper’s warnings very seriously. Even when Hooper and Brody go out on the water at night, and find the dead body of a local fisherman floating in the half-submerged hull of his wrecked boat— and a great white tooth more than three inches long stuck in the boat’s wooden bilge— Mayor Vaughn insists that the captured tiger shark is the one that’s been causing Amity so much trouble. The fact that the shark’s belly contains not the slightest trace of human remains doesn’t change Vaughn’s mind, either. The beaches are reopened, and all Brody can do is hedge Vaughn’s bet by setting up a boat patrol a few hundred yards out from the shore.

The price of all this wishful thinking is the worst Fourth of July in the island’s history. The shark— and it is indeed an immense great white— penetrates the cordon of police patrol boats, and kills a man rowboating in the inlet on the other side of Amity’s main beach. It also attacks Brody’s older son and a group of his friends, though all of the boys escape with nothing worse than a mild case of shock. With the summer business season now irrecoverably ruined, Vaughn and the selectmen at last agree with Brody that Quint must be hired to kill the shark, no matter how high his price.

And so begins the part of Jaws that most people remember best, in which Brody, Hooper, and Quint sail out on the latter man’s fishing boat to match wits, nerves, and muscles against the killer shark. It’s this phase of the film that secures Jaws its place as one of the all-time great seagoing adventure movies, while simultaneously maintaining the horror/monster credentials already established in the first two acts. Rarely has the subject of Manly Men Performing Manly Deeds received so efficient and effective a treatment from Hollywood as it does here, all the more so because, of the three men aboard the Orca, only Quint meets anything like the stereotype of the Manly Man. Hooper is a youthful, rich-kid scientist, as Quint so frequently and condescendingly reminds him, not realizing at first that Hooper’s line of work regularly puts him face to face with some of nature’s more dangerous creatures. And Brody, though obviously no coward (you try being a cop in the New York City of the early 70’s), has a deep-seated fear of boats and the ocean that the script leaves tantalizingly unexplained. (At one point, when Ellen asks him if there’s a technical name for his phobia, Brody replies, “Yeah— drowning.”) Even Quint doesn’t quite line up with the template, for he is just as frightened of the shark as Brody and Hooper, partly because of his harrowing experiences as a sailor aboard the USS Indianapolis on its doomed final mission in the summer of 1945, and partly because a 20-foot-plus great white is just intrinsically scary.

And make no mistake, the shark is scary. The anatomically flawed and rather rubbery-looking mechanical shark— affectionately named “Bruce” by its creators— is wisely kept mostly offscreen throughout the movie, the fish’s presence conveyed instead by that famous combination of ominous music and first-person camera perspective. Even in the climactic final act, we see relatively little of Bruce, and far more of the empty steel barrels Quint harpoons to his back in an effort to tire him out and take some of the fight out of him. (The idea here is that the shark will wear himself out swimming against the kegs’ buoyancy, which will eventually keep him within gun’s or harpoon’s or bang-stick’s reach of the surface.) Bruce’s limitations (and he resembles a real great white only slightly more closely than the model monster in The Great Alligator resembles a real crocodilian) are thus prevented from inflicting too much harm on the movie.

There are two things that really amaze me about Jaws, both of them having to do with the past and subsequent history of the creative team’s most prominent members. First, it’s easy to forget what a good director Stephen Spielberg used to be. Incredible as it may seem, the same man who gave us The Lost World: Jurassic Park and the retroactively sanitized version of ET: The Extraterrestrial currently making the rounds also directed Jaws. The light and efficient directorial touch Spielberg displayed in Jaws could scarcely be further from the heavy-handed belaboring of the obvious that he favors now, while the contrast between the pull-no-punches attitude that informs this movie and the contemptible squeamishness indicated by the digital removal of what few hints of violence the original ET possessed is simply astonishing. Saving Private Ryan aside, just try to imagine the Spielberg of today filming a scene that unflinchingly depicts the random and bloody death of a child mere seconds after implying the similar demise of a jolly, friendly dog!

But even more striking than Jaws’ place in the context of Stephen Spielberg’s career is its place in the context of Peter Benchley’s. Benchley, of course, wrote the novel on which Jaws was based, and he is given primary credit for writing the movie’s screenplay as well. All I can say in response to Benchley’s name on the credits here is, “this can’t be right!” You see, with Benchley, it isn’t a matter of, “man— remember back when he was good?” the way it is with Spielberg. Benchley was never good. Jaws the novel is one of the clunkiest, silliest, most inept pieces of fiction I’ve ever read; I find it frankly impossible to believe that the man who wrote it could have adapted it into the sleek, nuanced, believable story presented by the film version. If you’ve seen Jaws (and at this late date, I don’t see how you could not have), scan your memories for any moments that really stuck in your head. Maybe you’re thinking of Brody’s first sighting of the shark, and his subsequent stunned pronouncement that “We’re going to need a bigger boat.” Maybe you’re thinking of the delightful male bonding scene in which Hooper and Quint compare scars and trade the stories behind them. Maybe you’re thinking of Quint’s chilling (albeit historically inaccurate) reminiscence about the sinking of the Indianapolis and its grisly aftermath. Maybe you’re thinking of the terribly exciting (if not especially plausible) final showdown between Brody and the shark, in which Brody clings desperately to the sinking Orca’s mast, hoping against hope for a clear rifle shot at the tank of compressed air lodged in the shark’s gullet. If any of these scenes came to mind, you may be surprised to learn that not a single, solitary one of them appears in Benchley’s book! And much of what does appear in the book— the tiresome subplot about Ellen Brody’s marital angst and her resulting infidelity, the unnecessary and cheapening revelation that Mayor Vaughn’s opposition to closing the beaches stems ultimately from his ties to mafia-owned real estate on Amity, the crude and silly class-struggle subtext— is thankfully missing from the movie. Foremost among the reasons why Jaws stands out from its multitudinous imitators is the strength and honesty of its screenplay; even Vaughn’s refusal to close the beaches rings true because of the overwhelming pressure we see the merchants of Amity put on him, and because of the open invitation to self-delusion presented by the captured tiger shark. But neither strength nor honesty is anywhere to be found in the novels of Peter Benchley. It seems probable to me that Benchley’s co-scripter, Carl Gottlieb— or, in light of the piss-poor quality of Gottlieb’s own subsequent work, maybe even an uncredited someone else— did the lion’s share of the real writing, and that Benchley himself provided only the initial treatment.

Whoever really wrote it, though, Jaws works. The script plays to all of the young Spielberg’s greatest strengths as a director. It offers flashy and spectacular action, such a breathless pace that you scarcely notice its 124-minute length, and plenty of opportunities for Spielberg to display his matchless skill at manipulating the emotions of his audience. It’s just too bad old Steve deploys most of that talent these days in the service of such empty, phony movies. Watch Jaws to remind yourself how he ever got to be the big-shot he is now.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact