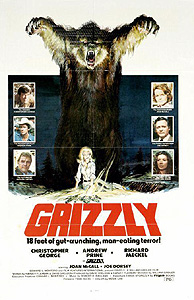

Grizzly/Killer Grizzly (1976) -**½

Grizzly/Killer Grizzly (1976) -**½

Despite their usual diet of fish, fruits, nuts, and insects, you’re just not going to find a modern land-going mammal much more intimidating than a grizzly bear; I mean, there’s the rhinoceros, the polar bear, and the Cape buffalo, but those three are pretty much it. (I suppose you could also add the Kodiak bear to the list, but since the Kodiak and the grizzly are merely two different sub-forms of the same species— Ursus arctos— I’m not going to. There’s a fair amount of evidence to suggest that the immense size of the Kodiak bear is due as much to environmental factors as it is to genetics, and that a grizzly raised under the same conditions would grow to be nearly as monstrous.) Nevermind that they very rarely do so— a full-grown grizzly bear can kill and eat a moose if it needs to, and any animal that can do that is worthy of a considerable amount of awe. And on the off-chance that you were to get it into your head to set a Jaws knock-off in the interior of the North American landmass, Ursus arctos is just about your only remotely credible choice for the monster (unless, of course, you wanted to go completely fanciful, and use Sasquatch, like the makers of Snowbeast). If the “trivia” section of the Internet Movie Database is to be believed, producer/screenwriter Harvey Flaxman got precisely that idea into his head after recalling an incident from his youth in which he had some sort of run-in with a grizzly while on a camping trip. And considering that it was a rip-off of a big-time blockbuster he and his partner, David Sheldon, were writing, it could hardly be more appropriate that the director who would bring their story to the screen should be William Girdler.

When we last saw Girdler, it was two years earlier, and his American International Exorcist clone, Abby, was being sued off the screen by Warner Brothers. It’s tempting to speculate that Girdler’s participation in the movie that would become Grizzly might have had something to do with why Warner (who had reputedly been approached first for backing by Flaxman and Sheldon) passed on the project, but who really knows? Either way, Girdler got up to his old tricks again, and when people call Grizzly “Jaws in the woods,” it’s no idle figure of speech!

Among the very few respects in which Grizzly does not copy Jaws is in delaying the first attack until well after the opening scene. Rather than beginning with something at least potentially shocking or exciting, Grizzly kicks off with what amounts essentially to a park ranger pep rally. Michael Kelly (Christopher George, from Pieces and Graduation Day), the head ranger at whatever national park this is supposed to be, gets together with a few of his subordinates to deliver some encouraging words in the face of what promises to be an off-season of unprecedented busyness. After sending the rest of the rangers on their way, Kelly takes a moment to be unconvincingly romantic with his photographer girlfriend, Allison Corwin (Joan McCall, of Devil Times Five and Rape Squad), whose father (Cockfighter’s Kermit Echols) owns the park’s biggest and poshest lodge. Meanwhile, Tom (Tom Arcuragi, from UFO: Target Earth), one of the younger and studlier rangers, administers a false scare to a couple of girls on a camping trip up one of the mountains. The real “scare” comes— finally— once Tom has moved on, as a treetop-height POV shot accompanied by much grunting and growling closes in on the campers, dismembers one of them, and then chases the other to an abandoned cabin. The second camper figures she’s more or less safe as long as she stays put inside, but man, is she ever mistaken. The apparently giant bear that was chasing her demolishes the whole back side of the cabin, and that’s the end of her.

When the two girls still haven’t checked in with the ranger station as per Tom’s instructions by about an hour before sundown, Kelly organizes a search party; Allison accompanies the rangers on the search for no really good reason. There isn’t a whole lot left of either camper when the search uncovers their bodies (literally in one case— the bear buried her corpse for later consumption), and Dr. Samuel Hallet (Charles Kissinger, of Abby and Asylum of Satan) gives Kelly his unsurprising verdict that the girls were attacked and killed by a very large bear. (Sadly, at no point does anybody ever proclaim, “This was no camping accident!”) The thing is, though, that bears of either species likely to be found in the park don’t typically eat any animal larger than a raccoon, and it’s extremely rare for even a grizzly to kill a human except in defense of a cub. Kelly found no trace of any cubs, and there’s no mistaking the partially-eaten condition of the two bodies.

So we’ve already got our Brody, and we’ve got a likely Quint candidate in the form of helicopter pilot Don Stober (Andrew Prine, from Simon, King of the Witches and The Evil). Our Hooper wannabe arrives right about now in the form of biologist Arthur Scott (Richard Jaekel, of The Green Slime and Mako: The Jaws of Death), whom Kelly calls in because he was the one who supervised the relocation of the park’s bear population some years ago— as Kelly puts it, Scott knows every bear in the park personally. The deaths of the campers (and Kelly’s subsequent orders to close the region of the park where those deaths occurred) also bring in our Mayor Vaughn figure. When park supervisor Charles Kitteridge (Joe Dorsey, from The Visitor and Stewardess School) gets wind of what’s going on, he comes on the run to make as much trouble as humanly possible. It’s hard to see why, since there’s nothing remotely comparable to Amity’s Fourth of July weekend for the killer bear or the attendant negative publicity to disrupt, but every time Kelly makes a move, you can rest assured that Kitteridge will be there to second-guess him and make things just a little bit worse. Case in point: rather than relying upon Kelly and his rangers to catch the bear (although, to be fair, the animal’s third victim is a ranger herself, so maybe a little outside assistance really is in order), Kitteridge invites a huge army of trigger-happy rednecks in for a big ol’ bear-shootin’ party. The bear quite rapidly exposes just how little the hunters are worth when it mauls one of them (albeit not fatally) and makes a mockery of an attempt by several more to trap it using what they presume— wrongly— to be its cub as bait. This should come as no surprise to anyone, because by this time, Scott has come to the rather startling conclusion that the bear they’re after isn’t one of the park’s regular population, but rather a freak holdover from prehistory— a monster bear fifteen feet tall on its hind legs, whose habits are far more predatory than those of any modern bear save perhaps the polar species. (An aside: There was indeed an enormous and highly predatory bear roaming around North America in prehistoric times, although it didn’t get anywhere near as big as fifteen feet. Unfortunately, that bear was called Arctodus simus, while Scott explicitly identifies his “prehistoric” bear as Ursus arctos horriblis— which is the scientific name of the grizzly subspecies typically found in the interior of the American northwest today. Note also that no explanation is even hinted at that could account for a breeding population of giant, predatory, and potentially man-eating bears going unnoticed in the Rocky Mountain region for as much as a million years, let alone how even a single such animal could have evaded Scott’s tagging and relocation project.) That, needless to say, is just a bit more bear than anybody on the scene right now is prepared to deal with.

Grizzly was apparently William Girdler’s most successful movie— at least if you measure a film’s success in dollars taken in at the box office. It probably isn’t a coincidence that it is also more brazen even than Abby in its enthusiastic ripping off of another, more famous picture. Nevertheless, it’s immediately evident that Girdler and his compatriots learned well the lesson of the Abby-related litigation, for in Grizzly, they managed to take a story which duplicates Jaws almost plot-point for plot-point, and yet develop it in such a way as to make it impervious to lawsuits for plagiarism. Nevermind that there’s a clear one-to-one correlation between the characters here and those in Grizzly’s model. Nevermind that nearly every set-piece from the Spielberg film has been duplicated completely without shame (Don the pilot even gets to deliver an obvious counterpart to Quint’s “sinking of the Indianapolis” monologue!), and that most of them even occupy approximately the same space in the narrative. Because it’s a park ranger instead of a police chief; because it’s a bear instead of a shark; because it’s a helicopter instead of a fishing boat; because it’s a light antitank rocket launcher instead of a cylinder of compressed air— for those reasons and a dozen more like them, Universal wouldn’t have had a leg to stand on in court, and Grizzly was able to ride the Jaws bandwagon unmolested, even though its most conspicuous feature is its uncommonly open thievery.

There’s another thing Grizzly has in common with Abby, too. Despite its almost xerographic similarity to Jaws in story terms, this movie displays only the faintest and most occasional glimmer of the greatness which it was designed to cash in on. Most of its major characters are either lifeless (Kelly), irrelevant (Allison), or damnably irritating (Scott), and only Don Stober is played by an actor who is really capable of selling his performance. Girdler’s efforts to ape Spielberg’s tactics for imparting menace to the monster founder upon his inability to devise a treatment of the bear which is both sensible and consistent. For example, when I saw that first bear’s-eye-view shot before the attack on the campers, I thought, “That’s pretty neat— he’s got the camera way up high to demonstrate that we’re seeing through the eyes of something far larger than a man.” The trouble, however, is that bears, though they are certainly capable of doing so, generally don’t walk more than a few steps at a time standing up on their hind legs; when the POV cam is in motion, it really ought to be much closer to the ground. It also doesn’t help that two different bears, of two different species, were used to represent the killer grizzly. Leaving aside the fact that both animals are visibly much smaller than we’ve been told, it’s a serious problem when the monster bear frequently changes size, color, and even body form from one shot to the next. The final showdown seems almost deliberately absurd, as one character obliterates the bear with a rocket launcher immediately after another fails (well, duh…) to beat it into submission with the butt of a rifle. Even the most effective scene in the film— round two of Arthur Scott’s encounter with the killer grizzly, which not coincidentally is also the movie’s one truly original moment— is compromised by thoughtless editing which ruins the sense of timing on which it hinges. Yet again, Girdler has accomplished no more than to trip over his own feet in a moderately engaging manner.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact