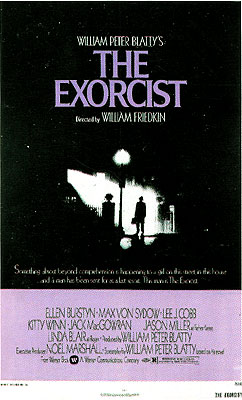

The Exorcist (1973/2000) ****Ĺ

The Exorcist (1973/2000) ****Ĺ

Considering some of the crap Iíve been writing about lately, I think itís about time we had a look at another acknowledged classic. And it seems to me that the re-release of The Exorcist presents me with a perfect excuse to do just that. Not only was The Exorcist one of the best horror movies of its decade, it was almost certainly the most important, generating phenomenal audience responses wherever it played, giving rise to an entire genre of low-rent ripoffs, and insinuating itself into the culture in a way that no horror film since Psycho had managed to do. How many hundreds of times in the last 25 years have you heard or seen somebody use this movieís imagery as a shorthand for demonic possession or to make a point about fantastically ill-behaved children? Alright then-- you see my point. And while it was making headlines and packing in crowds, it was also ushering in a new era in the history of the horror film, helping to spark a renaissance in the genre with its implicit promise that, henceforth, horror movies would take no prisoners in their renewed assault on the senses of the audience. The most incredible thing about The Exorcist is how hard-hitting, how genuinely shocking it remains today, even to a person like me who has just about seen it all.

It is also in some respects the most literal adaptation of a novel to film that Iíve ever seen. In a way, this is not surprising, because William Peter Blatty, who penned the screenplay, was also responsible for the very effective book on which it was based. That novel was itself supposedly inspired by a series of curious events that occurred in 1949, while Blatty was studying at Georgetown University in Washington, DC. That year (or so the story goes), somewhere in the Maryland suburbs of the nationís capital, a young boy suddenly became the center of an outbreak of poltergeist-like activity. His parents, at their witsí end, eventually took him to see their minister, who in turn referred the boy to the Jesuits. It was the ministerís opinion that the boy exhibited all the classic signs of demonic possession, as recognized of old by nearly all denominations of the Christian faith. By the mid-20th century, however, only the Roman Catholic Church preserved the rite of exorcism in the United States, and so the minister (a Lutheran) advised the concerned parents to set aside whatever doctrinal prejudices they may have had, and turn to the priesthood for assistance. The exorcism was performed, and by all accounts the boy grew up to lead a normal, productive life. That story, which, if Blatty is to be believed, was covered fairly extensively in the Washington newspapers at the time, spent the next twenty years fermenting in the authorís mind, until in the early 1970ís, it spawned The Exorcist.

The film begins at the site of an archaeological dig in northern Iraq. (Or at any rate, the 1973 version does-- the 2000 reissue restores a more or less pointless 30-second shot of a rowhouse in Georgetown before the opening credits.) The man in charge of the excavation is an elderly Jesuit priest with a heart condition, a man by the name of Father Lancaster Merrin (Max von Sydow, a Swedish thespian of considerable accomplishment, but not so much so as to make him unwilling to appear in the occasional exploitation flick-- look for him in Dreamscape and as Ming the Merciless in the 1980 version of Flash Gordon). His dig has turned up something that the old man finds very disturbing. In a stratum of earth where no such thing has any reason to be found, one of his colleagues has discovered a medallion bearing the image of St. Joseph. This is pretty weird, but Merrin seems to be more interested in an artifact that he himself finds in the sand very near to where the medallion was hidden. The object is the broken-off head of a small ceramic figurine, depicting a monkey-like visage topped by a crested helmet. It is the same face that adorns a much larger limestone statue elsewhere in the excavated ruins, a statue that depicts a fearsome humanoid monster with four wings, taloned feet, and what looks for all the world to be a colossal snake growing from its crotch. Something about the statue and the strange juxtaposition of the medallion with the broken figurine gives the old priest the idea that the time has come to return to America. ďThere is something I must do,Ē he tells his Iraqi colleague before leaving.

Meanwhile, in Georgetown, two people who do not yet know each other are about to have their lives turned inside out by something far beyond either oneís experience or understanding. One is another Jesuit, Father Damien Karras (Jason Miller, whose debut here would keep him busy with made-for-TV horror movies for the rest of the decade-- Vampire and The Henderson Monster, to name a couple). Karras is the psychiatric counselor for the Georgetown chapter of his order, and he no longer feels as though he is capable of performing his duties. His faith in God is long gone, and he thus feels he is in no position to help his patients, many of whom come to him with their own crises of faith. And on top of it all, his aged, infirm mother seems to be taking a sharp turn for the worse (indeed, she will die in a state-run nursing home before much more time has elapsed). The other character whom we now meet is a divorced actress named Chris MacNeil (Ellen Burstyn). She is in Georgetown shooting what looks to be a truly terrible movie, and it seems that something strange is happening to her 12-year-old daughter, Regan (Linda Blair, whom this picture would start on a long and glorious career in B-movies, helping her to land parts in such films as Hell Night and Chained Heat). Regan has acquired an imaginary friend (something you generally see with much younger children), has begun struggling in her school work, and has started telling strange and fantastic stories-- that her bed shakes at night, preventing her from sleeping, for example.

Then one evening, while her mother throws a cocktail party for a varied assemblage of Georgetown luminaries, Regan awakens and comes downstairs to the living room, where she tells one of her motherís guests, an astronaut scheduled to embark on a mission in only a few days, that ďYouíre going to die up there,Ē and then proceeds to piss all over the carpet. Later that night, after the girl has been tucked back in again, her bed starts shaking-- as sheíd been telling her mother it did-- with incredible violence, such that even Chris MacNeilís weight added to the bed has no effect. The next day, Chris takes Regan to see a doctor.

Reganís visit to the hospital is one of The Exorcistís most harrowing scenes, not because of anything she does (though she certainly causes quite a scene), but rather because of the ghastly and torturous tests that are administered to her. If you have trouble with needles, I suggest you watch this scene with a good, strong drink in your hand. Trust me on this; I have no fear of needles whatsoever, and what goes on here still makes me squirm. The idea behind the tests is that Reganís doctor (Letís Scare Jessica to Deathís Barton Heyman) believes she has a lesion on the temporal lobe of her brain, and that that lesion is responsible for her bizarre behavior. The violent shaking of the bed, or so the doctor says, is also a symptom of Reganís illness; her lesion gives her convulsions, and it is these that cause the bed to shake when she lies on it. Itís obvious that Chris doesnít entirely believe the doctor (and neither do we-- the man couldnít be any more full of shit if you used him as a storage bin for lawn fertilizer), but she goes along with his plan for Reganís treatment because she hasnít any better ideas herself. When the test results come in, we see that Chris was right not to believe. None of the tests has turned up a single thing that could be interpreted as evidence of a lesion.

The shit really hits the fan a few nights later, when Chris comes home from work to find the house apparently empty but for her daughter (the housekeepers have gone home for the night, and thereís no sign of Chrisís assistant, Sharon Spencer [Kitty Winn, of The House that Would Not Die]) and the window to Reganís room open to the frigid winter air. When Sharon returns home from what she explains was a short trip to the store to pick up Reganís meds, Chris learns that the younger woman hadnít left Regan alone. As far as Sharon knew, the girl was being watched by Burke Denning (Jack MacGowran, from The Fearless Vampire Killers, or Pardon Me, But Your Teeth Are in My Neck, who died only months after he finished working on The Exorcist), Chrisís close friend and the director of her current film. But Denning is also a floundering alcoholic, so it comes as less than a total surprise to Chris and Sharon to see that he has run off. We in the audience, on the other hand, are thinking thereís another, rather more sinister possibility, a possibility that has something to do with those police cars and ambulances Chris passed on her way home. And just as we are thinking that, a homicide detective named Kinderman (Lee J. Cobb, who also died shortly after his appearance here... hmmm...) comes to Chrisís door to inform her that Burke Denning has just been found dead at the bottom of the long, stone staircase that serves as the walkway down the drastically sloping alley that leads past her house.

Kinderman also talks to Damien Karras. The reason for his interview with the priest concerns a recent desecration of the church to which Karrasís order is attached. For reasons that he does a terrible job of explaining (I seem to recall it making slightly more sense in the book), Kinderman believes that the person who vandalized the church might also have killed Burke Denning, whose body was in a condition that could not easily be explained by a fall alone. It was a long fall, to be sure, but it generally takes more than a fall to turn a manís head around 180 degrees. And because Reganís bedroom window (which was open the night Denning died, I hasten to remind you) overlooks the alley staircase, while the MacNeil house itself was the last place Denning was seen alive, Kinderman has begun to suspect that whoever killed the director did so inside Reganís bedroom, and then pushed his body out the window. So begins an investigation that will have Kinderman spending a lot of time in the vicinity of the MacNeil house.

Meanwhile, Reganís aberrant behavior is becoming more extreme by the day. She talks in strange voices, injures herself apparently against her will, and has even begun manifesting what look like psychokinetic powers. The big turning point comes when Chris hears her daughter screaming one afternoon, and rushes to her bedroom to find its entire contents flying through the air as though a tornado had descended upon it. Worse yet, she finds Regan sitting on her bed, stabbing herself over and over again in the crotch with a crucifix, bellowing ďLet Jesus fuck you!!!!Ē in a guttural, inhuman snarl. When Chris tries to restrain her, Regan belts her across the face with the strength of a man many times her size, sending her sailing into the far corner of the room. Chris barely has time to recover before dodging out of the way as Reganís dresser comes skidding across the room to crush her. Then, as Chris lies panting on the floor behind Reagan, the debris of the bedroom still swirling around her, the girl twists her head completely around to pierce her with a glare of demonic savagery. ďDo you know what she did? Your cunting daughter?Ē Regan asks her terrified mother in Burke Denningís voice.

Faced with something like that, there is simply nothing a doctor or a psychiatrist can say that will render the situation comprehensible. One of the psychiatrists does have a suggestion, though, for a desperate, long-shot treatment. Chris could take her daughter, who is acting as though she were possessed by some sort of demon, to a priest for an exorcism. At first, Chris finds the idea too much to swallow-- ďYouíre saying I should take my daughter to a witch doctorÖ?Ē-- but her desperation is such that she goes almost immediately to Father Karras. Karras is, to say the least, less than enthusiastic about Chrisís idea. He is, after all, a psychiatrist himself, and even if he were not, it stands to reason that a man who has lost his faith in God has also lost his faith in the devil. But Chris persists, and ultimately convinces Karras to at least come to see Regan. To make a long story short (yeah, I know-- itís a bit late for that), Reganís performance for Karras, though ambiguous, is suggestive enough of demonic possession to make Karras seek permission from his superiors to perform the exorcism.

And this is where Father Merrin returns to the story. As you might imagine, priests who had performed exorcisms were something of a rarity in 1973. Merrin, however, had done just that while he was a missionary in Africa fifteen years before. He is thus the natural man for the job, and Karrasís bosses send word to him at the upstate New York monastery where he has been staying since his return from Iraq. The old priest rushes down to Georgetown, and the battle between him and Karras on the one hand and Reganís devil on the other is joined. Whoever said demons were cowardly had obviously never met this one.

So then, what was added to the film for its 2000 re-release, and what effect do those additions have? Most of the restored footage comes in brief snatches; a line or two of dialogue here and there, the new opening I mentioned, a new ending in which Kinderman talks briefly with Karrasís friend, Father Dyer (William OíMalley, also a Catholic priest in real life), about the outcome of the case. Essentially, what weíre seeing here is a new phenomenon in the world of cinema-- not a directorís cut, but rather a screenwriterís cut. Included in the new version of The Exorcist is much of what Blatty wrote that, after it had been filmed, director William Friedkin decided was unnecessary or counterproductive in a movie that would require significant cuts to bring it down to a still-comparatively-long two-hour running time. For the most part, I agree with Friedkin. The restored footage is, by and large, non-essential, and merely exaggerates the lurching, episodic feel that the first half of the movie already possessed, while the new/old ending is outright bad, bringing an otherwise very powerful movie to a close on a note of bland vapidity. There are, however, a few additions that really do add something to the film, or which could have had their inclusion been handled more skillfully. The first of these is an early round of medical testing that introduces the character of Dr. Klein and serves as our introduction to the idea that Chris has noticed Regan behaving oddly. This scene could have solved a slight problem in the original version, in which Chris seems too clueless for too long regarding her daughterís supernatural affliction. However, the scene makes no sense at the point in the movie where it was interpolated, because the only strange things weíve seen Regan do at that stage are play with a Ouija board and complain once about her shaking bed. The other new/old scene is really just a cheap shock, but it also happens to be one of the best cheap shocks ever committed to film. This is, of course, the famous ďspider walkĒ scene, in which, with absolutely no warning at all, Regan runs down the stairs on all fours on her back and attacks Chris and Sharon. Friedkin originally cut the scene because he never got what he considered a satisfactory emotional response from Ellen Burstyn to this particular affront. Again, I have to agree-- this guy really knows what heís talking about when it comes to his directorial decisions-- but the re-issue version gets around the problem by only showing us the first half of this sequence. As it appears in the reissue, the scene ends abruptly when Regan reaches the bottom of the stairs. This staccato editing increases the sceneís shock value exponentially, transforming it from a botched good idea to a marvelously executed, low-down dirty trick on the audience that hits like a pneumatic drill to the testicles.

But thereís one more addition to the movie, one that calls attention to something that has always puzzled me about The Exorcist. Iím not talking about new footage this time, but rather about new images inserted into footage that had been in the film from the very beginning. Perhaps the coolest thing about the reissue version of The Exorcist are all the ďghost imagesĒ that keep popping up for fractions of a second when Reganís demon is about to show its hand. Occasionally, these images are of the winged statue from Merrinís excavation in Iraq. More often, they take the form of a face that was occasionally glimpsed for a frame or two at a time in dream sequences in the original version. This face is much creepier than it has any right to be. Itís just a person of indeterminate gender with black and white grease paint applied so as to make him/her dimly resemble Lon Chaney Sr. in the 1925 version of The Phantom of the Opera. But sometimes the simplest tricks are the most effective, and there have been a couple of nights since I watched The Exorcist for this review that Iíve had trouble getting to sleep because I keep seeing that fucking face when I close my eyes! The new version makes much more extensive use of this inexplicably disturbing image. It is visible for a split second when the lights go out in one scene. In another, it appears superimposed over Reganís face. It shows up from time to time in dark corners throughout the film, always oriented so that it seems to be watching Chris MacNeil. The implication is that this face is that of the demon, and the fact that images of the statue from Iraq also appear in the MacNeil house suggests that the statue represents the evil spirit too. What I find so puzzling is that these are the only hints present in the movie of something that was a major theme in Blattyís novel. The possession of Regan MacNeil, or so the book has it, is a grudge match between the Babylonian demon Pazuzu and Father Merrin. It was Pazuzu that Merrin drove out of the boy in Africa fifteen years before the events of The Exorcist, and the demon has been itching for a rematch ever since. That broken figurine buried beside the St. Joseph medallion was the demonís way of issuing a challenge to Merrin. ďIím coming,Ē it tells the priest, ďand this time, Iím going to kick your ass.Ē But the movie handles this issue in such a way that only those who have read the book or who have a passing familiarity with Babylonian demonology (I am fortunate enough to fall into both categories) are likely to catch the nuances of whatís going on. When I saw the film for the first time (before Iíd read the novel or become acquainted with Pazuzu from other sources), all I could make out was that the demon inside Regan somehow knew who Merrin was, and was somehow connected with the archaeological dig in Iraq. The more frequent appearance of the old statue in the reissue version makes the connection a little clearer, but there is still only the faintest hint that the demonís previous encounter with Merrin is the entire reason for Reganís possession. It seems odd to me that Blatty would bury so deeply the lynchpin of his novelís plot and yet take the trouble to reproduce entire long stretches of dialogue verbatim when adapting that novel for the screen. All I can think of by way of explanation is the possibility that, to Blatty (who, as the author, had something of an advantage spotting the pattern woven by the threads of his plot), the relationship between Merrin and the demon seemed so obvious that it need only be sketched out by implication and innuendo.

That lapse of judgement on Blattyís part is one of the reasons why The Exorcist doesnít quite make it to a fifth star in my opinion. The other reason has to do with the filmís climax. Frankly, itís a bit of an anticlimax. By the time the priests have arrived to perform the exorcism, Regan has been strapped down to her bed and her room stripped of anything she could possibly use to hurt herself or anyone else. While this is certainly realistic (if I were the mother of a possessed kid, taking away all the sharp or heavy objects would be the first thing I would do), it has the effect of greatly diminishing Pazuzu/Reganís power to frighten the audience at the crucial juncture in the story. At a time when she ought to be looking more dangerous than ever, her motherís sensible precautions have turned Regan into little more than a very ugly child with Touretteís Syndrome. She still has the ability to mount a formidable psychic and psychological assault on Merrin and Karras, but it is obvious that there will be no repeats of the sort of intensely physical attacks she made earlier on her mother and the doctors. Nevertheless, The Exorcist retains its stature as a true classic of modern cinematic horror, and the shadows it casts over the genre remain just as long and just as dark as they were in the early 1970ís.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact