The Phantom of the Opera (1925) ****

The Phantom of the Opera (1925) ****

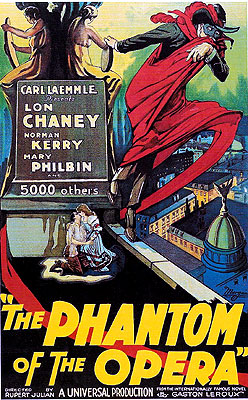

Before you go and ask me, yes-- I did in fact just review The Phantom of the Opera not that long ago. But that was a different Phantom of the Opera-- the crappy one from 1943 with Claude Rains just kind of hanging out not getting a chance to do anything because all the director cared about was the goddamned singing. That movie was a big-ass mistake, of the sort that major studios usually make when they try to out-do themselves. You see, Universal had already committed The Phantom of the Opera to film once before, with such breathtaking success that only an idiot would tempt fate by trying to top it. That film featured Lon Chaney Sr., one of the greatest stars of the silent era, in the title role, at a time when he was at the peak of his powers. It is a legitimate cinematic milestone, and despite the fact that comparatively few people today have actually seen it, it is nevertheless a part of the mythology of 20th-century America in much the same way as Universal’s later Dracula and Frankenstein, and just about everybody has seen at least a still or two of the remarkably effective makeup that Chaney created for the role. And it is this original, definitive Phantom of the Opera that I draw your attention to now.

The 1925 silent version represents, to the best of my knowledge, the only serious attempt ever made to film Gaston Leroux’s novel more or less as he wrote it. The story has been streamlined a bit, its pace quickened substantially, and a gaudy new ending has replaced the low-key (but also sort of sappy) conclusion of the book, but on the whole, this movie is extremely faithful to its source material. We begin with a pair of businessmen closing the deal to purchase the famous Paris Opera House from its previous owners, who one suspects have had more than enough of something, and would like to get while the getting is good. Before the old owners leave (but after the papers are safely signed), one of them mentions that the Opera is supposed to be haunted. The new guys scoff, but when they follow the old owners’ suggestion that they have a look in box five, they stop laughing right quick. There in the private balcony, just as the men said there would be, is a man in a black cloak, who seems to vanish without a trace when the startled investors turn their backs for a split second. The new owners aren’t the only ones to see the Opera Ghost that night; several of the ballerinas see a shadowy figure skulking around backstage, as do some of the stagehands. But much stranger than anything anyone sees is what’s going on at that very moment in one of the dressing rooms. Christine Daae (Mary Philbin, from The Man Who Laughs), one of the Opera’s up-and-coming singers, is holding a curious conversation with a voice that seems to emanate from the very walls of her room. The voice hints that it has been coaching Christine in secret, that it is responsible for the girl’s remarkably rapid growth as a performer. It also says something about the day coming soon when it will be able to take on physical form and vie for Christine’s love as a man.

That last part isn’t exactly what the Vicomte Raoul de Chagny (Norman Kerry, who had earlier appeared alongside Chaney in the 1923 version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and would do so again in The Unknown two years later) had expected to hear when he made the decision to eavesdrop outside Christine’s door. Chagny is Christine’s lover, and truth be told, he’s jealous enough of the raw fact of the girl’s career as a singer, even without mysterious vocal coaches hiding in the walls, scheming to win her away from him. But the vicomte keeps his suspicions to himself for the moment, and the film then turns our attention to jealousy of another sort.

While she certainly deserves to be, Christine is not really the star of the Paris Opera. That distinction belongs to another girl by the name of Carlotta (Mary Fabian). She’s sort of a homely thing-- graceless, chubby, bad posture, doesn’t wear wigs well-- and we are led to believe that she’s not really all that great of a singer. All she really has going for her, in fact, is her belligerent mother (Virginia Pearson), who happens to be talking the ears off the owners of the Opera while Christine confers with her mysterious mentor. Apparently somebody has been sending Carlotta threatening notes, promising some kind of violence if she does not relinquish the lead female role in the upcoming production of Faust to Christine. Carlotta’s mom naturally suspects that the girl herself is ultimately responsible, but she’s wrong, of course. While the parties to the argument all have their backs turned, another threatening letter, written on the same black-bordered stationery as the notes delivered to Carlotta, appears on the Opera owners’ desk. It reiterates the points already made in the previous letters, and concludes with a warning that, if Christine Daae is not given the role, the production of Faust will take place “in a cursed house!”

But nobody ever heeds such letters, certainly not in horror movies. When the Opera puts on its rendition of Faust, it is with Carlotta in the lead, and the consequences are pretty much as advertised. The house lights flicker menacingly throughout the show, and at a climactic moment in one of Carlotta’s solos, the huge chandelier plunges from the ceiling into the audience. Carlotta, smart girl that she is, starts calling in sick a lot after that.

So Christine steps up to take her place, and in no time at all, Carlotta is pretty much forgotten. Christine’s day in the sun is not to be a long one, however. Shortly after her first assay in the role of Marguerite, the voice comes to Christine again and instructs her to stand before her mirror. She does, and the glass swings open to reveal a long passageway leading into the bowels of the Opera house. The voice calls to her again, telling her to step inside, and it is not long after she does so that she meets her benefactor at last. The meeting doesn’t really go as either one had hoped. For her part, Christine is justifiably alarmed by the man’s demeanor, and is even more disturbed by the mask that conceals his face. Her mentor, on the other hand, seems to have expected a rather warmer reception from the girl-- one that involved a little less shrieking and fainting, at the very least. But at least with her out cold, the mystery man has less trouble getting her onto the back of his horse and leading her down to his home beneath the fourth sub-basement of the Opera house.

When Christine comes to, she puts the pieces together fairly quickly. Her benefactor is, of course, the legendary Phantom of the Opera, about whom the flighty little girls in the ballet troupe spend so much of their time chattering in hushed tones. It seems that he’s been living down here in what used to be a Commune-era dungeon for many years, avoiding all contact with other human beings, and on the basis of his mask, it’s not hard to guess why. He’s been very busy, converting the place into a fairly lavish apartment, with several sumptuously appointed rooms (and a few others tricked out in a rather more sinister manner, as some of our heroes will learn to their disadvantage later) and even a pipe organ, on which he plays for Christine some of the music from his own unfinished opera, Don Juan Triumphant. On the whole, it’s all very civilized and genteel. Okay, the guy sleeps in a coffin, but we can forgive a few eccentricities, right? Perhaps, but Christine has a bit more difficulty with that than we do, and when she sneaks up behind him and yanks off his mask, she finds she absolutely cannot forgive what a monstrously ugly freak her host is. This is one of those situations where you kind of have feel sympathy for both sides. I mean, how would you like to have a guy whose face looks like a goddamned skull, who lives in a secret lair hundreds of feet below the earth, and who sleeps in a fucking coffin ask you if you’ll be his girlfriend? Then again, how would you like to be the poor fucker doing the asking with all of those strikes against you, especially when you and the girl you’re asking out got along perfectly well before she knew what you and your house looked like? Considering how hopeless the situation looks, I’d say they do a pretty good job of finding a compromise. The Phantom (his name is Erik, and we will later learn that he is an escapee from the infamous Devil’s Island prison) agrees to allow Christine to return to the surface, but only so long as she promises never to see Raoul de Chagny again.

Of course, promises made under duress are made to be broken, and Raoul is the first person Christine seeks out when she gets back upstairs. She sends him a note saying that she will appear at the Bal Masque, the big-ass costume party the Opera throws every year, and that she will explain where she’s been for the past couple of days when she and Raoul meet up. But the note also admonishes Raoul to be careful, as she “will not be alone.” The masquerade scene that follows is one of the highlights of the film. It was shot in an extremely primitive version of Technicolor, and many more recent video prints of the movie preserve this then-flashy gimmick-- catch one of these if you can. Christine and Raoul do manage to link up, but they do not do so unobserved. True to Christine’s warning, Erik is in attendance as well, dressed as Poe’s Red Death (it’s a great costume). He follows the two lovers to the roof of the Opera to spy on their conversation, and he is not happy at all to hear his “girlfriend” plotting to flee to England with Raoul the next night, as soon as her performance is finished. (In the print I saw most recently, a fantastic 1996 restoration of the film as it appeared for its 1929 re-release, the scene when Erik spies on Christine and Raoul is almost too cool for words. Picture this: the two lovers are seated at the foot of a huge neoclassical statue of a topless, winged woman while Erik watches them from his perch between the statue’s wings, still in costume from the ball. Originally, this scene was in black and white, but for the re-release, the Technicolor process was applied to Erik and Erik only! The result is a really startling visual, with the Phantom’s blood-red cape flapping in the wind like a demon’s wings in the middle of the otherwise monochrome shot. It’s worth seeking out this particular version for that alone.)

Given Erik’s temperament, it’s hardly surprising that he throws a major monkey wrench into the escape attempt by arranging to kidnap Christine right off the stage in the middle of her act, nor is it too big a shock to see the Phantom kill a couple of stagehands who get in the way of his counterplot. And it is at this point in the movie that we finally learn the identity of a character we’ve been seeing off and on in the background since the very beginning. This man, who is poorly made-up to look like he hails from somewhere in the Middle East (he’s simply called “the Persian” in the novel), turns out to be a secret policeman by the name of Ledoux (Arthur Edmund Carewe, who was lucky enough to successfully make the transition to the talkies when they took over the movie industry at the end of the decade-- look for him in Doctor X and The Mystery of the Wax Museum), who has been on the Phantom’s trail for many years. Ledoux introduces himself to Raoul when Erik abducts Christine, and offers to help him rescue the girl. As the two descend into the labyrinth of tunnels beneath the Opera, and as Erik makes another play to force Christine to be his lover, another chain of events lurches into motion that seems to signal tough times ahead for the Phantom. One of the stagehands Erik killed had a brother-- also a stagehand-- and that brother is now out for revenge. When the man stumbles upon one of the trap doors that Erik uses to get around, he rushes out to one of his hangouts, and raises a torch-bearing mob that seems to consist of the whole of the Parisian proletariat. This is that gaudy new ending I mentioned, and yeah-- gaudy is definitely the word. The question is, who will get to Erik first, the comparatively sympathetic Raoul and Ledoux, or the stagehand’s bloodthirsty mob?

It’s possible to quibble with a few scenes here and there (some of the climactic goings-on in Erik’s lair are a bit too Ian Flemming for my taste-- though the blame for these lies with Gaston Leroux and not the screenwriter), but it really is difficult to overpraise The Phantom of the Opera. If you’ve never seen a silent before, the completely different style of acting might take some getting used to, but this movie will fully reward your perseverance. Mary Philbin, Norman Kerry, and especially Lon Chaney are nothing short of amazing. Despite having to rely entirely on gesture and facial expression to put their performances across, they manage a depth of feeling that puts all but the best of today’s actors to shame. And their acting is surprisingly free of the cartoonish physical exaggeration that often characterizes the performances in silent films, though it is certainly less naturalistic than what we are accustomed to today. The three leads are also well served by the script, which reflects a deep understanding of the original novel’s strengths. In marked contrast to the botched remake that Universal would vomit up 18 years later, this movie succeeds in striking the delicate balance between the Phantom’s tragic and menacing aspects, and portrays the relationship between Erik and Christine in terms that make sense. The creators of this film also rightly realized that the conflict between Erik’s impossible love for Christine on the one hand and the embattled but ultimately viable relationship between her and Raoul on the other is the mainspring of the story. Everything else is at bottom a distraction, and can be safely left sketchy provided that the Erik-Christine-Raoul triangle is believable. It is. More than that, in fact-- it’s moving. I have a fairly long history of favoring remakes over the original versions (The Mummy, The Fly, and The Thing spring instantly to mind). But sometimes, they really do get it right the first time.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact