Frankenstein (1931) ***

Frankenstein (1931) ***

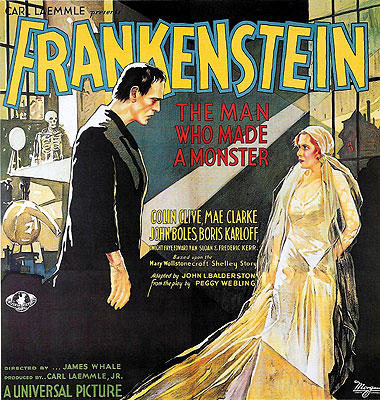

As further proof of my oft-made contention that the problem with Tod Browning’s Dracula is not the limitations imposed by its age, but rather an enduring shittiness that transcends time and place, allow me to submit James Whale’s Frankenstein. Like Dracula, Frankenstein was made in 1931, at the very beginning of the sound era of cinema, and at the birth of the horror movie in America as a distinct genre. Also like Dracula, it was based on a stage play that bore no more than a passing resemblance to a famous old novel that was, at the very least, well on its way to being recognized as a classic. Both films were produced for the same studio, used some of the same supporting players, and featured star-making turns for previously obscure actors in the role of the monster. You could scarcely ask for a pair of movies more amenable to direct comparison. And if you subject them to such an assessment, it is obvious that Frankenstein is by far the superior film, so much so that I wonder what anyone ever saw in its equally famous cousin.

Nevertheless, it must be said that the script itself is actually fairly weak, filled with overly facile situations and improbable behavior on the parts of many characters. Dr. Henry Frankenstein (Mad Love’s Colin Clive) and his hunchbacked assistant Fritz (Dwight Frye, from Dracula and The Crime of Dr. Crespi) are roaming about the countryside of some non-specifically Germanic European country collecting corpses. They rob a grave, they steal the body of a condemned man from the gallows— Fritz even sneaks into a lecture hall at the nearby university to steal a brain. As anyone in the Western world knows by now, the reason Frankenstein wants all these stiffs is that he believes he has unlocked the secret of life itself, and he wants to put his theories to the test in the most dramatic possible manner— by creating a human being. To that end, he has secluded himself in an abandoned medieval watchtower perched on a craggy peak outside of Goldstadt. The tower is both isolated and forbidding enough to be inaccessible to the curious and nettlesome, and tall enough to attract the lightning which Frankenstein needs to power his life-giving equipment; it would seem to meet the man’s special needs perfectly. But there are still two rather large flies in Frankenstein’s ointment. First, that brain Fritz stole from the university belonged to a violent criminal, a detail which the hunchback understandably kept to himself when he presented the pilfered organ to his boss. Thus, Frankenstein’s creation is likely to cause him no end of grief if in fact he is successful in bringing it to life. Secondly, Frankenstein is engaged to a woman named Elizabeth (chapterplay regular Mae Clarke, whom fans of the old serials may remember from King of the Rocket Men and The Lost Planet Airmen) back in his hometown, and he has been very bad about keeping in touch with his betrothed since he went off to study at Goldstadt’s university (the institution from which Fritz procured the defective brain).

Elizabeth herself trusts Henry, but his father, the Baron Frankenstein (Frederick Kerr), is convinced that the young man has found himself a mistress in Goldstadt. Baron Frankenstein insists upon going to see his son, and he brings along Elizabeth and Henry’s old friend Victor Moritz (The Last Warning’s John Boles— and no, I have no idea why Frankenstein and the Henry Clerval character have switched first names in this film, though I suspect the answer would bring me one step closer to figuring out why Mina Harker and Lucy Westenra keep trading names in the various Dracula movies). When they reach Goldstadt, Baron Frankenstein and his entourage are surprised to learn that Henry is no longer a student at the university. His old professor, Dr. Waldman (Edward Van Sloan, who is much better here than he was as Van Helsing in Dracula and Dracula’s Daughter), explains that Henry’s theories were “far in advance of this institution’s” and that Waldman himself considers Frankenstein’s ideas to be actively dangerous. Faced with the disapproval of his professor and his school, Henry did the only reasonable thing and dropped out to pursue his vision under less restrictive circumstances. Waldman thus doesn’t think it will do much good for Elizabeth, Victor, and the baron to try to talk him down from his lab at the top of the watchtower, but he agrees to go along with them anyway— after all, it’s worth a try, and Waldman would really like to see Henry give up his “mad” research.

The four travelers reach Henry’s lab just in time to interrupt his preparations for the big experiment. Though Fritz refuses them entry, Henry relents when he learns that Elizabeth is among the party on his doorstep. Of course, letting them in puts Henry in the awkward position of having to explain to them his plans for Tampering In God’s Domain, a subject he’d really rather not go into. But when Victor starts calling him crazy, on the basis of what Waldman told him about his old friend’s work, that gets Henry pissed enough to want to lay it all out for Victor and prove him wrong. He takes his father, Victor, Elizabeth, and Waldman on a brief tour of his lab, and then presents them with the “man” he has built out of whatever spare parts he could get his hands on (do you really need to be told that the thing under the sheet is Boris Karloff?). By this point, the thunderstorm that has been building all night has peaked, and Henry can no longer wait— the time has come to jump start his creature. While his friends and family look on, Frankenstein hooks the creature up to the impressive-looking electrical gear that fills most of the lab, and waits for lightning to strike the conductors on the tower roof. The machinery works like a charm, and the creature twitches to life with the very first captured discharge. Finally convinced of both Frankenstein’s sanity and his sexual fidelity to Elizabeth, Victor, the baron, and the girl herself return home, leaving Henry to tend to his creation.

Waldman, on the other hand, sticks around. He still thinks what Frankenstein has done is both crazy and wrong. He’s sure the creature is dangerous, and considering that it stands about six-foot-four and has shoulders like a linebacker, there’s probably something to his concerns. When Waldman tells Henry that the thing’s brain came from a deranged killer (Henry having just owned up to the theft of the brain from Waldman’s lecture hall), even Frankenstein starts to show some concern. Even so, there might still have been hope for the situation had it not been for Fritz. The hunchback, apparently thrilled at being presented at last with something even uglier and more wretched than himself, has taken to tormenting the creature for kicks. Eventually, dumb-ass taunts the thing a little too hard for a little too long, and it kills him, its savagery in doing so finally opening its creator’s eyes to the potential threat it poses. Frankenstein and Waldman decide that the creature must be destroyed, and after shooting it up with enough tranquilizers to put a moose to sleep, Waldman volunteers to do the dirty work, freeing Henry to return to his home and his impending marriage.

But the monster swiftly develops a tolerance for the sedatives Waldman uses, and it comes to on the operating table just as the professor begins the job of disassembling it a few days later. The monster likes the situation to which it awoke about as much as you or I would, and because it’s a great big hulking thing with a murderer’s brain, it’s also in a very good position to act on its displeasure. After strangling Waldman, the monster heads off down the road that passes by the watchtower, walking, as it happens, in the direction of the Frankenstein estate. The monster’s clumsiness and mental deficiency make it lots of enemies in Frankenstein’s hometown when it accidentally drowns a young girl who mistakenly figured it would make a good playmate; the creature gets so excited when the girl shows it how daisies float on the still surface of a pond that it tosses her in to see if she floats too! She doesn’t. The girl’s father discovers her body at about the same time that the monster gate-crashes Frankenstein’s wedding reception, and when the bereaved man and Frankenstein put their heads together, the result is a full-scale manhunt that ultimately traps the monster in a rickety— and highly inflammable— windmill. We all know how this one turns out.

As I said, we’ve got some problems here. To begin with, every single character is written as an empty stereotype, and few of the actors have much interest in raising theirs to a higher level through nuanced performance. It’s not so much that the acting is bad (though Frederick Kerr’s certainly is), but rather that it is mostly unimaginative, and that it reinforces the shortcomings of the screenplay rather than covering for them. Everyone but Colin Clive, for example, treats the “birth” of the monster as though it were no more unusual than a trip to the corner store for bread and cigarettes. I myself think that I’d have a slightly more emphatic reaction to seeing a sewn-together corpse come to life before my eyes than these people do. And I certainly wouldn’t just mosey blithely back home after seeing something like that, even if it had served to allay my fears that my son was cheating on his fiancee! I realize the blame for the latter absurdity lies with the screenwriter and not with the cast, but none of the actors even attempt to use their performances to make this foolishness any easier to swallow.

Then there are some elements of the screenplay that could not be made to work no matter what anyone did to downplay their ridiculousness. Why in Aten’s name would Frankenstein leave Waldman alone with the monster he has just decided is too dangerous to live? And furthermore, why keep the thing alive but sedated for long enough for it to develop a tolerance for the drugs? I mean, if you’re going to kill the thing, just fucking do it! Or to back up a bit in the flow of the story, why doesn’t Frankenstein do something to keep Fritz under control? He knows how strong and how short-tempered his monster is; surely a man smart enough to bring the dead to life is also smart enough to see that standing idly by while his hunchback lackey mercilessly annoys the thing is a formula for disaster!

What saves Frankenstein from its cast (Boris Karloff excepted, of course) and its script is James Whale. More than any other Universal horror film I’ve seen, Frankenstein displays the influence of the German expressionist directors of the silent era, and Whale made a smart move in borrowing from F. W. Murnau’s bag of tricks. Whale wields his camera like a man who knows what it can do, and though he doesn’t take as many chances with it as the Germans had before him (no location shots, for example), he makes the most of the relatively restrictive environment of the back lot and soundstage. In addition, Whale’s eye for visual composition is phenomenal, and the film is breathtaking to behold even when it’s at its dumbest. The sets are fantastic, and nearly every shot is laid out so as to take maximum advantage of their Old-World menace. The director lays on the atmosphere with a trowel, creating an environment that looks like a nightmare even if the continual raising of the bar for horrific imagery over the past 70 years prevents the movie from feeling like one to a modern audience. Karloff’s sympathetic portrayal of the monster and Jack Pierce’s groundbreaking makeup make their contributions, of course, but it’s Whale’s mastery of his craft that brings Frankenstein to life.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact