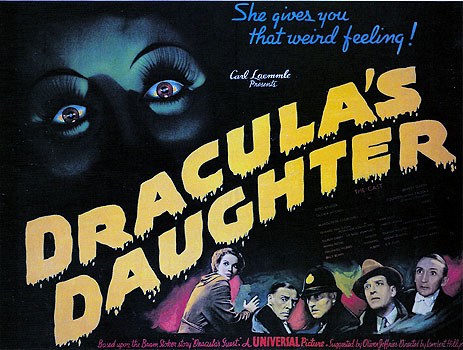

Dracula’s Daughter/ Daughter of Dracula (1936) -**

Dracula’s Daughter/ Daughter of Dracula (1936) -**

When Bride of Frankenstein succeeded in duplicating the success of the original movie, the folks in charge at Universal got it into their heads that a feminized sequel to Dracula could be a giant hit too. They’d been beaten to the punch, however, by David O. Selznick, a producer working in those days for the rival MGM studio. As early as 1933, Selznick had bought the rights to produce a film based on “Dracula’s Guest,” an orphaned vignette from the original draft of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, describing a meeting between Jonathan Harker and a female vampire on the road to Dracula’s castle, which had been published subsequently as a short story in its own right. This appears to have been an entirely strategic move on Selzinck’s part. The screen treatment he commissioned from John Balderston (who had written the stage play from which Universal’s Dracula was derived) could not possibly have been filmed without embroiling MGM in protracted copyright litigation with Universal, and in the end Selznick sold the option on “Dracula’s Guest” to the other company. (You can bet Selznick got a good price for it, too.)

Even then, there was a huge obstacle standing between what would become Dracula’s Daughter and the theater screen. In 1934, the heads of the major studios finally succumbed to intense pressure from press, public, and politicians to relinquish their power to override the Production Code Administration’s censorship directives, and after that, the Hays Office was in a much stronger position to dictate what went into the final cut of any film; it was the PCA’s opinion that Balderston’s script was totally unacceptable. Thus Universal had to start over from scratch. They hired James Whale, who had directed the two Frankenstein films, to write a screen treatment for the new movie, and it seems fairly likely that Whale would have ended up in the director’s chair had the film he sketched out ever actually been made. Whale’s proposal resembled Balderston’s in that it was for a serious film that would reunite much of the original cast and feature Bela Lugosi returning to the role that made him a star. It would have been a big, ambitious production, which would have required the studio’s full backing and support to be brought to life successfully. That’s not how it turned out, though. Instead, it seems that the Universal bigwigs had a look at Whale’s treatment and said to the director, “Now hold on here, James! We don’t think you understand the sort of movie we’re looking for. This is 1936-- the Great Depression is on! What we want is a movie where we can spend about $45 on sets, props, and costumes, and we want to pay the cast and crew in yo-yos.” James Whale wasn’t interested in making a movie like that, and neither was anybody else who had been involved in the original Dracula. And thus it was that there would be no Bela Lugosi in Dracula’s Daughter-- no Tod Browning, no David Manners, and no Helen Chandler, either.

In fact, the only member of the 1931 team who felt like signing his name to the half-assed crap-bucket the producers wanted was Edward Van Sloan. This is entirely understandable given the prospects that an actor of Van Sloan’s caliber would have faced in the days before direct-to-video soft porn, and so we begin our tale in the basement of Carfax Abbey, where Van Helsing (Van Sloan) has just driven a stake through the heart of Count Dracula. Two of England’s Most Incompetent Constables show up at the abbey for reasons unknown, and find Renfield’s body at the bottom of the basement stairs, where Dracula left it after he broke the man’s neck in the last movie. (At least the dummies playing the roles of the corpses are about the same size and shape as Bela Lugosi and Dwight Frye, even if their faces bear them not the slightest resemblance...) When England’s Most Incompetent Constables notice Van Helsing, they ask him to explain the situation, which he does in the naive manner to which we have become accustomed: he tells them that Dracula killed Renfield, and that he himself then killed Dracula, but that it’s okay, because the count had already been dead for 500 years when he did it. Fortunately for England, even its Most Incompetent Constables are smart enough to find Van Helsing’s story suspicious, and they arrest him, taking him and the two bodies back to the police station.

Soon thereafter, Van Helsing repeats his tale to Sir Basil Humphrey of Scotland Yard (The Return of the Vampire’s Gilbert Emery). The detective finds it no more credible than did England’s Most Incompetent Constables, and Humphrey informs Van Helsing that, if he intends to stick to his story, he will have to be charged with murder, in which case he will certainly be convicted and sent either to the gallows or to a hospital for the criminally insane. Now, if I were in Van Helsing’s position, I would be on the phone to my lawyer at this moment, but the old doctor further underscores the questionable nature of his sanity by calling a psychiatrist buddy of his instead. That psychiatrist is Dr. Jeffrey Garth (Otto Kruger, from Jungle Captive and The Colossus of New York), and he had been a student of Van Helsing’s. He’s also, or so the old man says, the only person who can help him.

Meanwhile, back at the police station, our friends the E.M.I.C.s are waiting for another Scotland Yard man to come collect the bodies of Renfield and Dracula. The higher-ranking of the two heads off to meet the detective’s train, leaving his cowardly partner to watch the stiffs. But before the sergeant can return, a woman in a black velvet cape with matching hood and veil (very stylish, I must say) arrives at the station to have a look at the body of Count Dracula. The cowardly E.M.I.C. tells her he has orders to let no one near the bodies, but the poor guy’s clearly out of his league here. The woman lifts her right hand and waves her enormous ring in front of the constable’s face, hypnotizing him. She then sneaks off with Dracula’s body, hauls it to the nearest patch of woodland, and burns it, conducting some sort of ceremony over the pyre.

The woman, as you might have guessed, turns out to be the count’s daughter. It’s never quite elucidated whether she’s a biological daughter or a daughter in the vampiric sense, but the point is that she hates being a vampire. She rushed off to England when word reached Transylvania that Dracula had been killed, partly to make absolutely certain the rumors were true, partly so that she could try to exorcise her father’s body in the hope that the procedure would free her from her own vampirism. No such luck. As her servant Sandor (Irving Pichel, of Torture Ship) tries to tell her, it’s going to take more than that to return her to the world of the living, and the very next night, she finds herself roaming the streets of London looking for prey.

But to return to Van Helsing’s legal troubles, Dr. Garth doesn’t believe the vampire story any more than anyone else, but he does agree to help the old man clear his name. He just isn’t sure how. Though he doesn’t initially realize it, the answer presents itself at a party that he attends with his secretary, Baroness Janet Blake (Marguerite Churchill, from The Walking Dead, and yeah, you read that right-- Dr. Garth has a noblewoman for a secretary). At the party, Garth is introduced to a Hungarian woman by the name of Countess Maria Zaleska (Gloria Holden). She, of course, is the same woman we just saw steal and burn Dracula’s body and then go out on the town to drink the blood of fools who think they’re about to get action. Zaleska becomes very interested in Garth when she hears he’s a psychiatrist; as she says, she’s got some willpower problems she’d like help with, and perhaps science can succeed where magic failed. Much to the dismay of his jealous secretary, Garth starts seeing an awful lot of Countess Zaleska, and it doesn’t take too long before he starts putting the pieces together. Van Helsing, of course, has noticed that somebody has begun prowling around London killing people using Dracula’s old MO, and he begins plying Garth with vampire lore just in time for the younger doctor to notice how much of it fits with Zaleska’s curious lifestyle.

Before long, Zaleska realizes the game is up, and she kidnaps Janet in an attempt to blackmail Garth into coming home with her to Transylvania to join her in eternal unlife. (She has decided that there’s no hope of her ever being cured herself.) Garth pursues the countess back to her homeland, and Van Helsing and Sir Basil Humphrey (who is beginning to take the doctor’s story more seriously than he’d like to admit) pursue Garth, the whole lot of them ultimately showing up in waves at Castle Dracula. When Sandor (to whom Zaleska had promised immortality many years before) hears his mistress make the same offer (though in this case, it’s more of a threat) to Garth, he takes it rather badly, and the vampire’s servant gets his trusty bow and arrow and just starts shooting. Sandor’s last victim before he himself is shot by Humphrey is the countess; as Van Helsing explains, a wooden shaft through the heart is all you need-- whether it’s an arrow or a stake is immaterial. (Though I would argue that the fact that the arrow hits Zaleska in the spleen rather than the heart is not...)

So let’s take a moment to assess this movie in context, shall we? Dracula, for better or for worse, was one of the most important horror movies of all time. Through it, Bela Lugosi became one of the biggest names of the first generation of horror stars. How many of you, on the other hand, have ever seen Dracula’s Daughter? How many of you had ever heard of Gloria Holden? That’s about what I thought, and both this movie and its star fully deserve their relative anonymity. The whole production positively reeks of a greed-driven desire to get any movie at all into the pipeline before the audience excitement generated by Bride of Frankenstein burned itself out, but Universal in the 1930’s was really too stuffy to put together a good shameless exploitation movie. Cynicism on this scale can create a fully enjoyable movie only when it produces exuberantly lurid trash, something Universal wouldn’t get a handle on making until the Laemmle family lost control of the studio during the following decade. But as bad as it is, I must admit that Dracula’s Daughter has a certain dopey charm to it that its predecessor lacks. Janet’s pointless cattiness toward Zaleska is rather fun to watch, as is the sadistic glee with which Sandor waves his mistress’s unwilling vampirism in her face. The most entertaining part of the movie, though, might be the way it draws attention to its predecessor’s extremely shaky grasp of time, precisely by attempting to pin down its own temporal setting more securely. Remember, the story of Dracula’s Daughter begins about ten minutes after the final scene of Dracula, so whenever that was ought to be the correct timeframe for the sequel as well. Dracula, though, wasn’t really set in any particular era-- or at least not consistently so. During the Transylvania phase of the picture, what we see accords best with the first half of the 1800’s, but in London, everybody’s dressed for contemporary times, and modern-day cars can be briefly seen in an establishing shot here and there, even though Dr. Seward's psychiatric practice is stubbornly Victorian. So it’s retroactively jarring when Janet goes driving around the English countryside in what looks to me like a 1930’s Rolls-Royce roadster, and even more so when Garth flies to Transylvania in a single-seat biplane noticeably more modern than the ones that shot King Kong off the top of the Empire State Building. Mind you, Dracula’s Daughter has its own, smaller-scale problem with Silly Putty Time. Like, does anybody want to venture a guess as to how Zaleska managed to hear of her father’s death and then get herself two thirds of the way across Europe, in such a way that the entire process took less than 24 hours? Anybody? I didn’t think so.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact