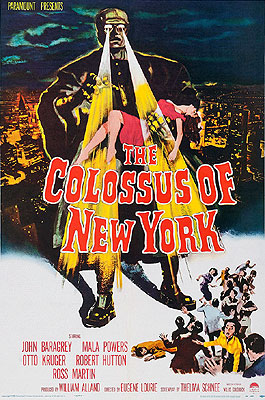

The Colossus of New York (1958) **½

The Colossus of New York (1958) **½

This is a pretty standard 1950’s “science run amok” flick in which misdirected idealism creates a monster that can be stopped only by the intervention of a pre-pubescent boy. Its only real distinction lies in the fact that the usual moral of these movies-- that intelligence, even genius, will inevitably be used for evil in the absence of old-fashioned God-fearing morality-- is stated rather more explicitly than is generally the case. In fact, if you were asked to come up with a single movie to use as an example of the way in which 50’s sci-fi reveals that era’s ambivalence toward the explosive growth of the role of science in modern life, The Colossus of New York would be a good place to start.

On the one hand, we have Dr. Jeremy Spensser (Spensser? Yeah, I know, but check out the newspaper headlines-- that’s actually the way the movie spells it). Dr. Spensser (Ross Martin, from Conquest of Space, who went on to be a voice actor on “Sealab 2020”) is a veritable renaissance man-- a physicist, a botanist, an engineer, all with equally spectacular success. His current project concerns an effort to develop new strains of edible plants so hardy that they can even be grown above the Arctic Circle, a program that, if successful, would solve the world’s food-production problems at a stroke. Dr. Spensser is not just a genius, though. He’s also a devoted father, a loving husband, and an all-around nice guy. In other words, he is the incarnation of science-as-benefactor. Such a shame, then, that he doesn’t survive the first fifteen minutes.

You see, Jeremy gets run over by a truck one day while running across the street to retrieve his son Billy’s toy airplane, which was blown out of the boy’s hand by a sudden gust of wind. Despite the fact that Spensser was dead pretty much the instant he hit the pavement, his father (Otto Krueger, of Jungle Captive and Dracula’s Daughter), a renowned and accomplished neurosurgeon, insists on having the ambulance take Jeremy not to the hospital, but to the elder Dr. Spensser’s elaborately-equipped home laboratory. Whatever “operation” Spensser performs on his son, it is insufficient to save his life, but as the movie progresses, we will increasingly get the feeling that saving Jeremy’s life in the usual sense was never on the older man’s mind.

The elder Spensser is, of course, the movie’s stand-in for the darker side of scientific advancement, the side that is so impressed with its own nearly god-like powers that it seems never to take a moment to consider what unintended consequences its work might have. In the immediate aftermath of Jeremy’s death, we witness a conversation between Spensser and John Carrington (Robert Hutton, from Invisible Invaders and The Vulture), a friend of Jeremy’s, that turns into a rather ugly argument over whether our humanity is solely the product of our intelligence, or whether some mysterious something else is at work. Carrington takes the latter position, talking grandly of the interaction of intelligence, bodily sensation, and the God-given immortal soul, while Spensser (who seems to be taking this debate just a little too personally) contends with stubborn passion that the brain is the immortal soul, or at least the closest thing to it that can actually be shown to exist. So it is less than surprising when it comes out that that last-ditch surgery he performed on Jeremy involved the removal of his son’s brain, which Spensser has somehow managed to keep alive in an aquarium in his lab.

This is where Jeremy’s brother, Henry (The Creeper’s John Baragrey), comes in. Henry is a mechanical engineer of no small talent, and his father has big plans for putting that talent to work. He wants Henry to build a robot body to house Jeremy’s brain, so that the world will not be deprived of the fruits of his genius. Henry doesn’t think this is such a good idea, but he is eventually convinced. We, on the other hand, know he was right the first time from the moment we first set eyes on the finished product; whenever anybody tries to put someone else’s brain into a machine that resembles an even bigger, even more dangerous-looking version of the Universal Studios Frankenstein monster, trouble is on the way. And sure enough, Jeremy is about as happy to return to the world of the living as a nine-foot-tall mechanical monster as the titular Bride of Frankenstein was when she first got a look at herself. When the first words your creation utters are, “destroy me,” it’s probably a good idea to give it what it wants.

The soundness of this argument is further underscored when Robo-Jeremy discovers that he now has powers of ESP-- he can see things happening even hundreds of miles away, as he does when he has a vision of a lethal collision between two ships out in the Atlantic Ocean. The movie never really bothers to invent an excuse for this development, and that’s probably just as well, when you get right down to it. Anyway, it makes it rather hard for Jeremy to concentrate on his research when he keeps having visions, and the fact that Henry keeps taunting him about being a huge, dead, ugly robot doesn’t exactly help, either. There’s a fair amount of sibling rivalry here, as you might imagine; apparently, Daddy always liked Jeremy better. And in fact, it’s Henry’s taunting that finally pushes Robo-Jeremy over the edge, accelerating his already inevitable slide into evil. Hey, everybody knows that living brains lack souls-- right?-- and as Carrington told us earlier, no soul = no conscience = no regard for human life.

I’m sure you can see where this is going, and I’m sure you can figure out who victim number one is going to be. And if I tell you that, while he was still alive, Jeremy had been part of a body of agricultural researchers in the employ of the United Nations, known as the International Food Congress, and that the new and improved Robo-Jeremy eventually has a change of heart-- or a change of fuel-pump, or something-- regarding the evolutionary wisdom of keeping the poor and starving alive, I’m sure you’ll be able to predict the general shape of The Colossus of New York’s climax, too. In parting, I’d just like to suggest that if you ever decide to put the brain of one of your deceased children into a robot body, for heaven’s sake don’t endow that robot body with superhuman strength, powers of ESP and mind control, and death-ray emitters in its eyes. If Henry and his father had shown a little more foresight in this department, everything would have turned out very differently.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact